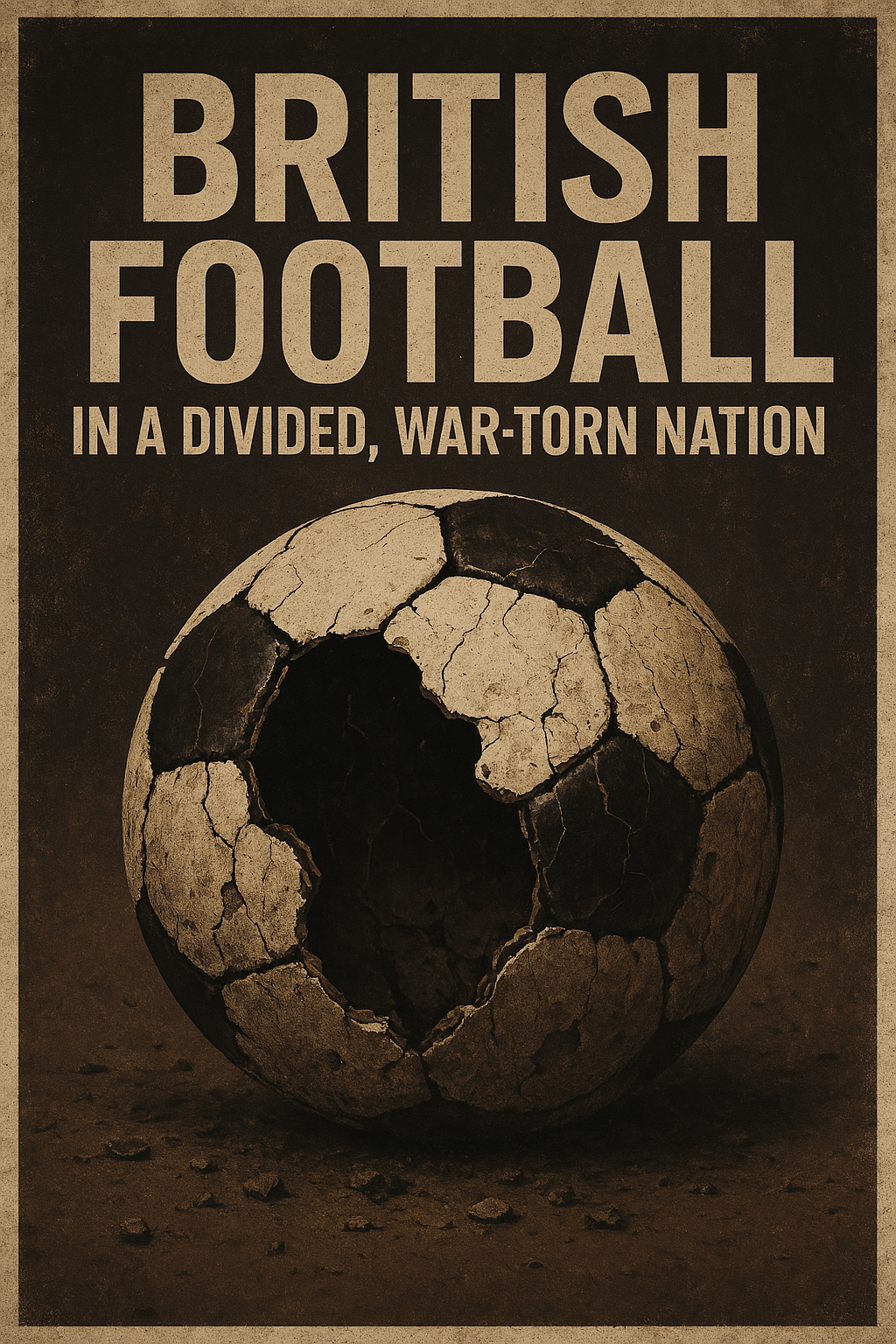

With politics in ruins and the economy reduced to ash, football—once the soul of Britain—faced a question that no one could answer: could a nation torn from its own past still find beauty in a goal?

For more than a century, football had been more than a sport in Britain. It was the glue between dockers and dukes, between steel towns and schoolyards. It was tradition passed from father to son, terrace chants echoing across generations, the thunder of boots on grass telling the story of a people.

But when Britain turned its guns on itself, even football could not survive.

🏟️ 1976–1983: The Death of the Beautiful Game

As the British Civil War spread across cities and generations, professional football collapsed under the weight of violence and fear. The English First Division—once the pride of the world—ceased to exist by 1977. League play halted. Fixtures were canceled. Entire clubs went dark.

- Wembley Stadium, where England had lifted the World Cup in 1966, was reduced to rubble during the Battle of London.

- Old Trafford burned during the Siege of Manchester, its pitch buried beneath ash and artillery shell.

- Anfield and Stamford Bridge were transformed into barracks and barricades.

The FA dissolved. TV contracts vanished. Sponsors fled. And fans who once filled the terraces with song now dug trenches and built barricades where ticket queues had stood.

Some players fled before it was too late. Others stayed and tried to keep the game alive. And some never made it out.

⚰️ The Martyrs and the Lost

The war spared no legends.

- Bobby Moore, the captain who once kissed the Jules Rimet Trophy beneath the Wembley arch, refused to flee his homeland. Branded a collaborator by Royalist forces, he was executed behind closed doors in 1983.

- Jock Stein, the Scottish manager who gave Celtic its golden age, died under Soviet fire in the streets of Glasgow while sheltering war orphans.

- Duncan Edwards, once called the greatest talent of his generation, was gunned down outside a Red Cross shelter in Manchester in 1978.

There are no statues. No commemorative plaques. Their memories survive only in whispers and worn photographs smuggled out of the country.

🌍 1984–1995: Two Nations, Two Games

With the war ended but the nation broken, British football fractured into two irreconcilable realities:

⚪ The Royalist Game in Exile

From the embers of the old FA, a diaspora league emerged in Canada and Australia, formed by exiled players, managers, and owners.

- Manchester United reformed in Toronto, their crest redrawn in mourning.

- Arsenal, West Ham, Spurs—all had clubs-in-exile, ghost teams carrying battered legacies.

- Kevin Keegan, Trevor Francis, Liam Brady, and Kenny Dalglish became wandering stars—British icons in foreign leagues.

The exiled FA petitioned FIFA for recognition. They were denied. England-in-Exile was a dream without a home.

🔴 The People’s Game Under Soviet Rule

In 1985, the United Commonwealth Football League was created in Soviet Britain. It was not sport. It was spectacle—used to feed propaganda, not passion.

- Clubs were nationalized, slogans replaced club mottos, and KGB officers stood where fans once cheered.

- Bryan Robson, once the pride of West Brom, became captain of a team that never played outside its borders.

- Peter Shilton, the legendary goalkeeper, remained under state surveillance—rumored to have attempted escape, only to be dragged back.

The People’s Game was joyless, hollow, tightly controlled. The roar of the crowd was replaced by choreographed clapping and mandatory attendance.

🚷 The International Exile

Britain, once the founding father of football, disappeared from the global stage.

- No England at the World Cup after 1982.

- Scotland, swallowed by Soviet rule, was banned from competition.

- Talented players took Irish, Australian, or Canadian citizenship to chase footballing dreams abroad.

In their place, the world watched new powers rise: Germany, Brazil, Argentina, France. The flag of St. George no longer flew. No anthems were sung. No flags were waved.

British football became a memory—faded, yellowed, and locked in a past no one dared to revisit.

📡 1990s: The Ghost Leagues and the Whispered Rebellion

And yet… in the ruins, football refused to fully die.

- In burned-out stadiums, children kicked balls made from rags.

- Underground leagues emerged—illegal matches played in the shell of Highbury, in car parks and tunnels, far from the eyes of the state.

- Fans smuggled in VHS tapes of Barcelona, Milan, and Marseille, watching magic that had once been theirs.

Football, like the British spirit, survived underground—hidden, defiant, dangerous.

And as Soviet influence began to weaken, as rebellion stirred again in cities and slums, football became more than a game. It became a symbol.

🔮 What Comes Next?

Three futures stood before the shattered goalposts of a nation:

- Return and Restoration

Could Britain, if reborn, rejoin the world of football? Could FIFA welcome back a nation that had once invented the game? - Resistance and Rebellion

Might football become the spark? A famous player, a rogue club, a unified league—leading not with slogans, but with goals? - Oblivion

Or had too much been lost? Would future generations know football only through foreign broadcasts and war stories?

Once, football defined Britain.

Now, it reflects what Britain has become—

Fragmented, grieving, yearning for a second half that may never come.

Leave a comment