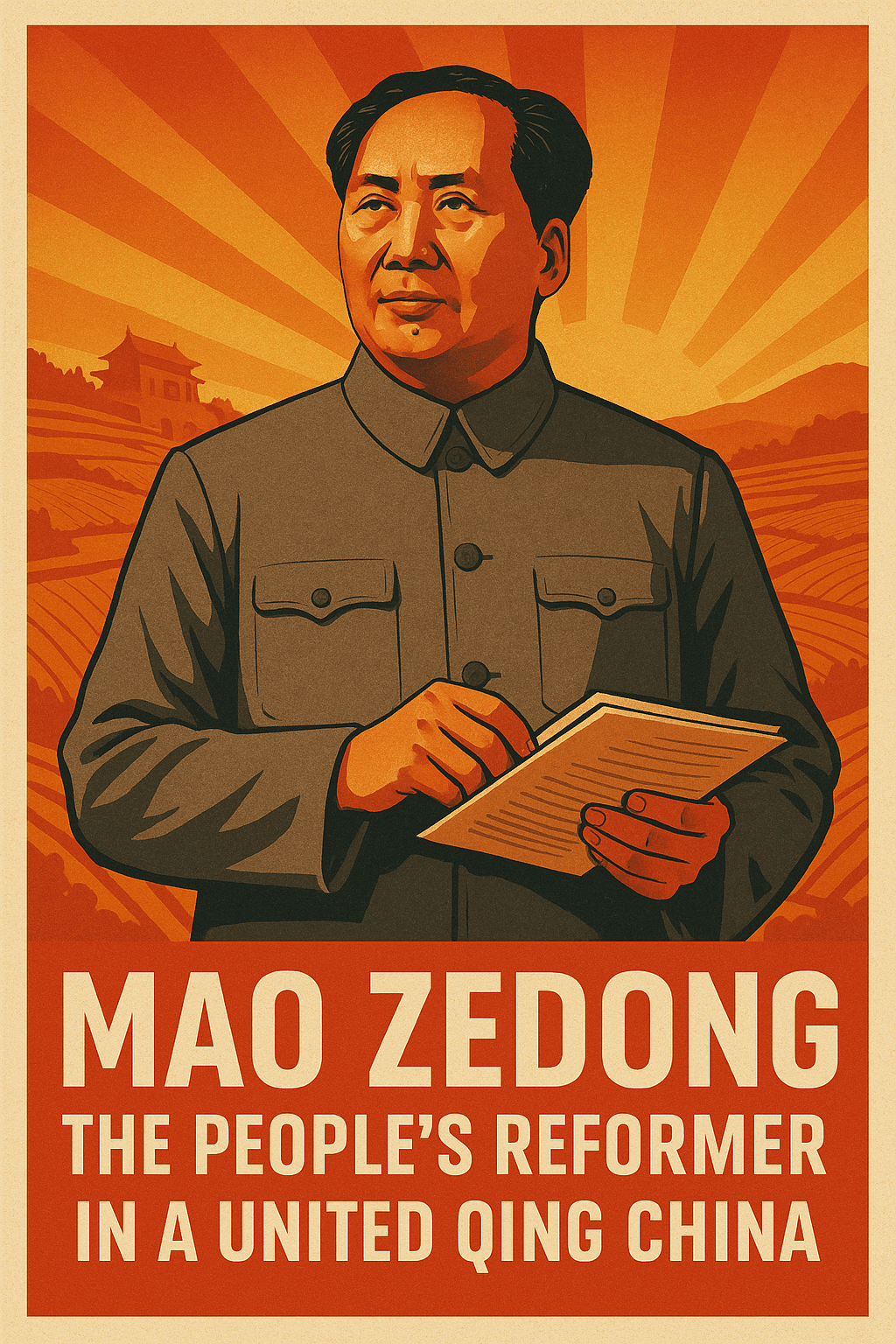

In this alternate timeline, where the Qing dynasty survives and evolves into a modern constitutional monarchy, Mao Zedong emerges not as a revolutionary leader but as a key figure in shaping socialist reform within a multi-party parliamentary system. Instead of spearheading class struggle, Mao becomes a transformative reformer working to uplift China’s rural poor and develop a uniquely Chinese model of socialism.

I. Early Life and Education (1893–1920)

Mao is born in Shaoshan, Hunan Province, in 1893 to a well-off peasant family. His early years are marked by exposure to rural hardship and Confucian education. However, the success of the Hundred Days’ Reform and the Qing Empire’s peaceful transition into a constitutional monarchy provides Mao with a stable environment for intellectual growth.

Benefiting from the modernized Qing education system, Mao studies in Changsha and later attends university in Nanjing, where he is introduced to socialist thought, liberalism, and the writings of Liang Qichao. Inspired by reformist ideals, he rejects violent revolution and embraces gradual, community-centered change.

II. Rising Political Influence (1920s–1940s)

1. Provincial Reformer: Returning to Hunan, Mao participates in land reform programs and rural education initiatives. He becomes known as a “people’s advocate,” pushing for tenant rights, fair taxation, and government investment in public services.

2. Entry into National Politics: By 1932, Mao is elected to the Guomin Yuan (National Assembly). Working within the Reformist Party, he becomes a prominent figure in debates on agrarian reform, cooperative farming, and public healthcare. His proposals are praised for their practicality and moral grounding.

3. Minister of Rural Development: Appointed to the Qing Cabinet in 1947, Mao oversees the nationwide Rural Reconstruction Movement. His initiatives include:

- Redistributing unused imperial lands

- Establishing farmer cooperatives

- Expanding rural healthcare and education

His work earns him the nickname “The Farmer’s Friend.”

III. Ideological Clash with Stalin (1930s)

The 1930s witness a transnational ideological confrontation between Mao and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. While Stalin criticizes the Qing system as “feudal” and condemns Mao as a revisionist, Mao defends China’s peaceful path to socialism.

Mao’s essay “The Bridge, Not the Bomb” argues that socialism must be tailored to each nation’s realities. He critiques Stalin’s emphasis on violent class struggle and forced industrialization, promoting instead class collaboration, rural empowerment, and reform through pluralism. This debate shapes global socialism, with China becoming a model for non-revolutionary, democratic socialism.

IV. Socialism in the Qing Empire

In this timeline, socialism functions as a peaceful, constitutional force. The Socialist Alliance emerges as a legal political party, advocating worker protections, nationalized industries, and universal healthcare.

Key policies enacted with Mao’s influence include:

- Land redistribution laws

- Labor unions with legal backing

- Government-funded rural clinics

- Free public education and technical training

By the 1950s, socialist ideals are deeply integrated into the Qing constitutional order, supported by a coalition of reformists, monarchists, and moderate conservatives.

V. Later Years and Legacy (1950s–1976)

Mao retires from active politics in the 1960s but continues advising on rural policy and writing essays on Confucian socialism. He is awarded the Order of National Service by Emperor Puyi in 1965.

He dies peacefully in 1976, the same year as Emperor Puyi, and is buried with honors. He is remembered not as a revolutionary, but as a national unifier, reformer, and tireless champion of China’s rural population.

Statues of Mao stand not in military posture, but beside irrigation systems and schoolhouses. His portrait hangs in agricultural colleges, and his writings are studied as blueprints for ethical, people-centered governance.

Conclusion: A Socialist Legacy Without Revolution

In this alternate Qing dynasty, Mao Zedong becomes a symbol of pragmatic socialism. His peaceful advocacy for the peasantry and his refusal to embrace violent upheaval demonstrate a path where reform, tradition, and modern governance harmonize. The legacy of Mao in this world is one of compassion, cooperation, and transformation through law, not war.

Leave a comment