The assassination of Liang Qichao in 1926 plunges the Qing Empire into one of its most precarious moments. Liang, a towering figure in the Qing government and a symbol of reform, is killed by a radical nationalist while delivering a speech in Nanjing. His death shocks the nation, destabilizes the political landscape, and threatens to undo decades of progress. As protests erupt and the National Assembly fractures, the Xuantong Emperor, Puyi, steps forward as a mediator and negotiator, determined to preserve unity and prevent civil war.

This event becomes a defining moment for Puyi as a statesman. His ability to navigate the crisis and secure a fragile truce with Sun Yat-sen and the Nationalists ensures the survival of both the Qing monarchy and China’s constitutional system.

The Context of the Crisis

The Rising Nationalists

By 1926, the Nationalist Party (Minzu Dang), under Sun Yat-sen’s leadership, has grown into a powerful political force. Though the Nationalists participate in the Qing Empire’s constitutional system, their ultimate goal is the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic. Liang Qichao, as Prime Minister and leader of the Reformist Party, had skillfully balanced the Nationalists’ demands with the monarchy’s interests. His death removes that balance.

The assassination sparks violent protests in major cities like Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Beijing. Nationalist leaders blame conservative monarchists for Liang’s death, while monarchists accuse the Nationalists of exploiting the tragedy to destabilize the government. Factional fighting breaks out in the National Assembly, and several provincial leaders begin mobilizing their private militias, threatening the fragile unity of the empire.

Puyi’s Position

At just 20 years old, Puyi has already begun stepping into his role as a constitutional monarch, guided by Liang Qichao and other reformists. Liang’s assassination leaves Puyi deeply shaken, but it also forces him to take on a more active political role. Recognizing that the survival of the monarchy depends on preventing further violence, Puyi decides to personally mediate between the Reformists, the Nationalists, and the conservative monarchists.

The Negotiation: Beijing, Winter 1926

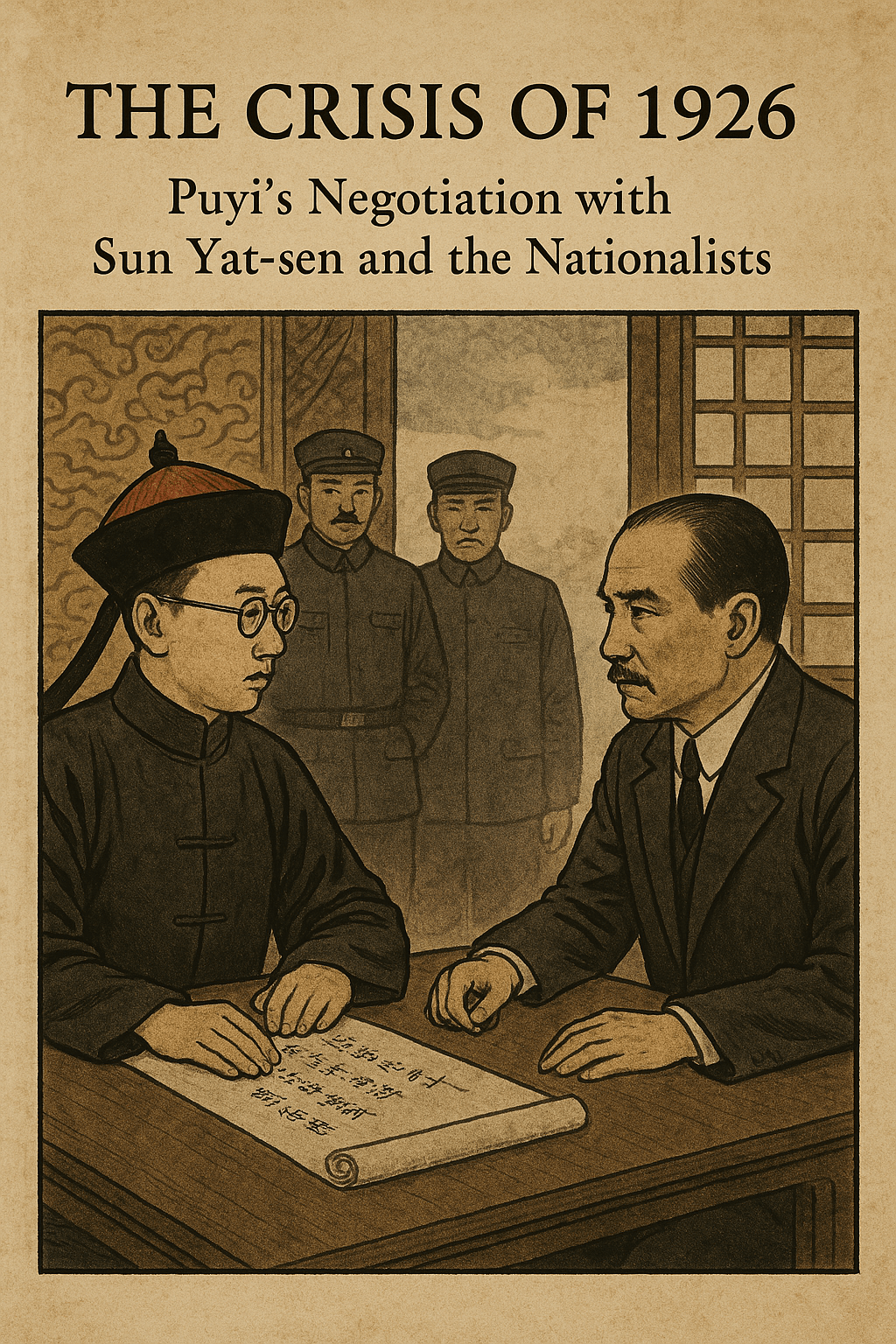

In November 1926, Puyi invites Sun Yat-sen and other key Nationalist leaders to the Forbidden City in Beijing for direct talks. The meeting is unprecedented—this is the first time in Qing history that an emperor meets face-to-face with leaders of an anti-monarchist movement. Despite skepticism from his advisors, Puyi insists that dialogue is the only way to prevent chaos.

The Key Figures at the Table:

- Puyi: The young Xuantong Emperor, determined to preserve the monarchy and constitutional stability.

- Sun Yat-sen: The leader of the Nationalist Party, representing republican ideals but willing to negotiate within the constitutional framework.

- Tang Shaoyi: A moderate Nationalist and trusted ally of Sun, who favors compromise over revolution.

- Zhang Zongchang: A conservative monarchist general, present to ensure the army’s interests are represented.

- Zhang Jian: A leading industrialist and Reformist Party member, advocating for economic stability and peace.

The Negotiation Process

Opening Statements: Puyi Appeals to Unity

The negotiations begin with a formal address by Puyi. The young Emperor emphasizes the need for national unity and invokes both Confucian values and modern constitutional principles:

- “The people of China are watching us, hoping for peace. They do not wish to see the sacrifices of the last three decades undone by factionalism and violence.”

- “If the monarchy falls into chaos or the National Assembly collapses, foreign powers will exploit our division. Let us act as stewards of China, not its destroyers.”

Puyi’s appeal surprises the Nationalists, many of whom had expected him to act as a passive figurehead. His calm demeanor and genuine desire for reconciliation soften the hostility in the room.

Sun Yat-sen’s Demands

Sun Yat-sen, though initially skeptical of Puyi’s sincerity, agrees to negotiate. He lays out the Nationalist Party’s demands, including:

- A Fully Elected Government: The Nationalists demand the abolition of appointed seats in the upper house of the National Assembly, particularly those reserved for Manchu nobles and Confucian scholars.

- Military Neutrality: The Nationalists accuse conservative monarchist generals of meddling in politics and demand that the Beiyang Army remain apolitical.

- Expanded Suffrage: Sun pushes for universal suffrage, extending voting rights to all men and women, including the rural poor.

- Anti-Corruption Reforms: Sun insists on stronger anti-corruption measures to prevent wealthy elites and monarchists from dominating the government.

Puyi’s Counteroffers

Puyi acknowledges the legitimacy of many of Sun’s demands but works to preserve the monarchy’s symbolic authority and the multiethnic balance of the empire. His counteroffers include:

- A Gradual Phase-Out of Appointed Seats: Puyi proposes reducing the number of appointed seats in the upper house over a ten-year period rather than abolishing them outright, ensuring a smoother transition.

- Civilian Oversight of the Military: Puyi agrees to establish a Military Neutrality Act, preventing generals from holding political office and placing the Beiyang Army under civilian oversight.

- Suffrage Expansion with Safeguards: Puyi supports expanding suffrage but insists on retaining property or education requirements for rural areas initially, fearing that sudden universal suffrage could destabilize provincial politics.

A Tense Compromise

The negotiations stretch over two weeks. At times, tempers flare, particularly between the Nationalists and conservative monarchists. Sun Yat-sen threatens to withdraw from the talks multiple times, frustrated by what he perceives as slow progress. However, Puyi’s diplomatic skill and personal humility keep the discussions on track.

In the final days of the talks, Puyi makes a bold move:

- He personally apologizes for the failures of the monarchy to adequately protect reformists like Liang Qichao.

- He proposes a joint Memorial Act to honor Liang Qichao, declaring him a national hero and committing to implementing his vision of a modern constitutional state.

Sun Yat-sen, moved by Puyi’s sincerity, agrees to the compromise. The two men shake hands, a gesture that becomes one of the most iconic moments in modern Chinese history.

The Beijing Accords of 1926

The negotiations result in the Beijing Accords, a landmark agreement that preserves the constitutional monarchy while addressing key Nationalist demands. Key provisions include:

- Abolition of Appointed Seats in the Upper House by 1936.

- The Military Neutrality Act (1927): Establishes civilian control over the military.

- Expanded Suffrage: Voting rights are extended to include more rural citizens, with universal suffrage targeted for the 1930s.

- Liang Qichao Memorial Act: A national holiday is established to commemorate Liang’s contributions to reform.

- Commitment to National Unity: Both sides pledge to work within the constitutional system and avoid violence.

Aftermath and Legacy

The Beijing Accords stabilize China at a critical moment. Sun Yat-sen and the Nationalists remain in the system, focusing their efforts on electoral politics rather than revolution. Puyi emerges from the crisis as a respected statesman, earning the nickname “The Scholar Emperor.”

While tensions between monarchists and republicans persist, the accords ensure that disagreements are settled through debate and legislation rather than violence. The success of these negotiations cements the Qing Empire’s trajectory as a modern constitutional state, with Puyi and Sun Yat-sen remembered as the architects of this fragile but enduring peace.

Leave a comment