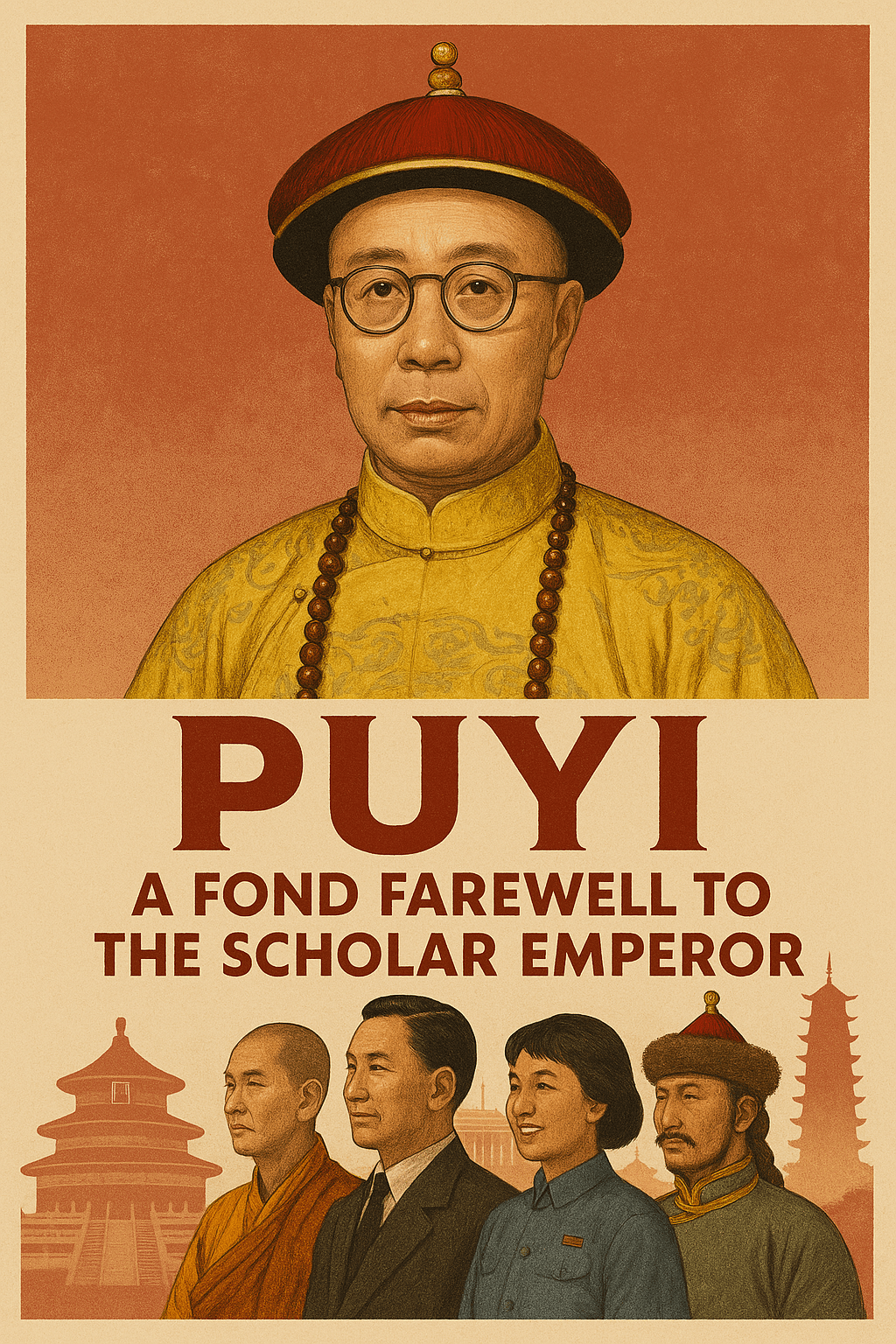

In this alternate timeline, Puyi—the Xuantong Emperor—lives not in exile or obscurity, but as one of modern China’s most revered constitutional monarchs. His death on October 17, 1976, at the age of 70, marks the end of a transformative era in Chinese history. Puyi’s final decades are defined not by decline, but by statesmanship, cultural diplomacy, and a powerful legacy of unity in a time of global division.

A Statesman for a New Age: Puyi’s Final Years (1950s–1976)

A Monarch of Diplomacy and Modernity

As China matured into a modern constitutional monarchy, Puyi served as its moral compass and symbolic guide. Though his formal powers were limited, his presence loomed large in both domestic governance and global affairs. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, he became a respected figure in international forums, promoting peace, non-alignment, and pan-Asian cooperation. His leadership in the Pan-Asian Bloc positioned China as a bridge between the Cold War’s ideological camps.

National Unity and Ethnic Inclusion

Domestically, Puyi remained an anchor of stability in a rapidly changing society. He mediated between political factions, oversaw inclusive reforms, and fostered interethnic harmony, notably through efforts to integrate Manchu, Han, Tibetan, Uyghur, and Mongolian identities into a shared national narrative. His public persona, blending Confucian virtue with Manchu heritage, helped solidify his image as the “Scholar Emperor.”

Preparing for the Future

In his later years, Puyi gracefully began delegating ceremonial duties to younger members of the Aisin Gioro family. His goal was clear: ensure the monarchy remained a relevant and respected institution in the 21st century.

The Passing of a Monarch: Puyi’s Death and National Mourning

On October 17, 1976, Puyi died peacefully in the Imperial Summer Palace, surrounded by family and close advisors. His last words, later shared with the public, captured the essence of his life’s work:

“I have seen the dream of a strong and united China come true. My only wish is that this unity lasts forever.”

His death triggered a month-long period of mourning. Citizens across the country and the world paid tribute to the Emperor who had shepherded China through war, reform, and renaissance.

A Funeral of Past and Present: October 24, 1976

The Imperial Summer Palace and Vigil

Puyi’s body lay in state for three days at the Summer Palace. Surrounded by ceremonial incense, floral tributes, and banners bearing his most quoted speeches, the vigil blended Manchu traditions and Confucian rites. Millions of citizens participated in memorial services, while foreign embassies lowered flags in tribute.

The Procession to the Temple of Heaven

On the day of the funeral, a grand procession accompanied Puyi’s sandalwood coffin through the streets of Beijing. Carried on a gilded platform by ceremonial guards in dragon-embroidered robes, the cortege merged ancient ritual with modern pageantry:

- Confucian scholars, Buddhist monks, and Taoist priests led prayers.

- A military honor guard followed in modern uniforms, reflecting Puyi’s legacy as a peacemaker and strategist.

- Representatives from all walks of life—from rural farmers to scientists, from ethnic leaders to university students—walked behind, embodying the unity Puyi had worked so tirelessly to build.

The Ceremony at the Temple of Heaven

At the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests, beneath a blue-tiled dome once used by emperors to commune with the heavens, the funeral service took place.

Key moments included:

- Traditional Offerings of grain, jade, and silk to the heavens.

- Confucian Eulogies describing Puyi as “the bridge between past and future.”

- A ceremonial Manchu dance, a nod to his heritage.

- A 21-gun salute by the Imperial Armed Forces, followed by jet fighters forming the character 团 (“unity”) in the sky.

Foreign leaders—including Henry Kissinger, Indira Gandhi, Alexei Kosygin, and Takeo Fukuda—delivered tributes. Gandhi hailed him as a “philosopher-king of the modern East,” while Kissinger called him “the quiet architect of Asia’s balance.”

The Mausoleum of the Constitutional Emperors

Puyi was buried in a newly constructed mausoleum outside Beijing, designed to reflect both Qing imperial style and modern architectural aesthetics. His tomb bears a simple but powerful inscription:

“Here lies the Xuantong Emperor, who upheld the Mandate of Heaven in a modern age and united a nation through peace, wisdom, and dignity.”

A Lasting Legacy

Puyi’s death marked the end of a remarkable reign, but his legacy endured:

- National Unity: Ethnic minorities, urban elites, rural citizens, and foreign allies all came together in mourning, showing the strength of the inclusive empire he helped build.

- Political Continuity: His chosen successor, Aisin Gioro Hengqin, ascended the throne with minimal disruption, continuing the tradition of a modern constitutional monarchy.

- Historical Memory: Schools, parks, and diplomatic centers across China and Asia are named in his honor. His life becomes the subject of biographies, dramas, and museum exhibits, framing him as both emperor and educator.

Conclusion: The Emperor Who Bridged Eras

Puyi’s life stands as one of the most profound examples of personal and national transformation. Born into a collapsing empire, he died as the revered monarch of a modern, unified China—respected at home and abroad. His funeral was not just a farewell, but a celebration of what it meant to lead with humility, to govern through change, and to embody the soul of a nation.

Leave a comment