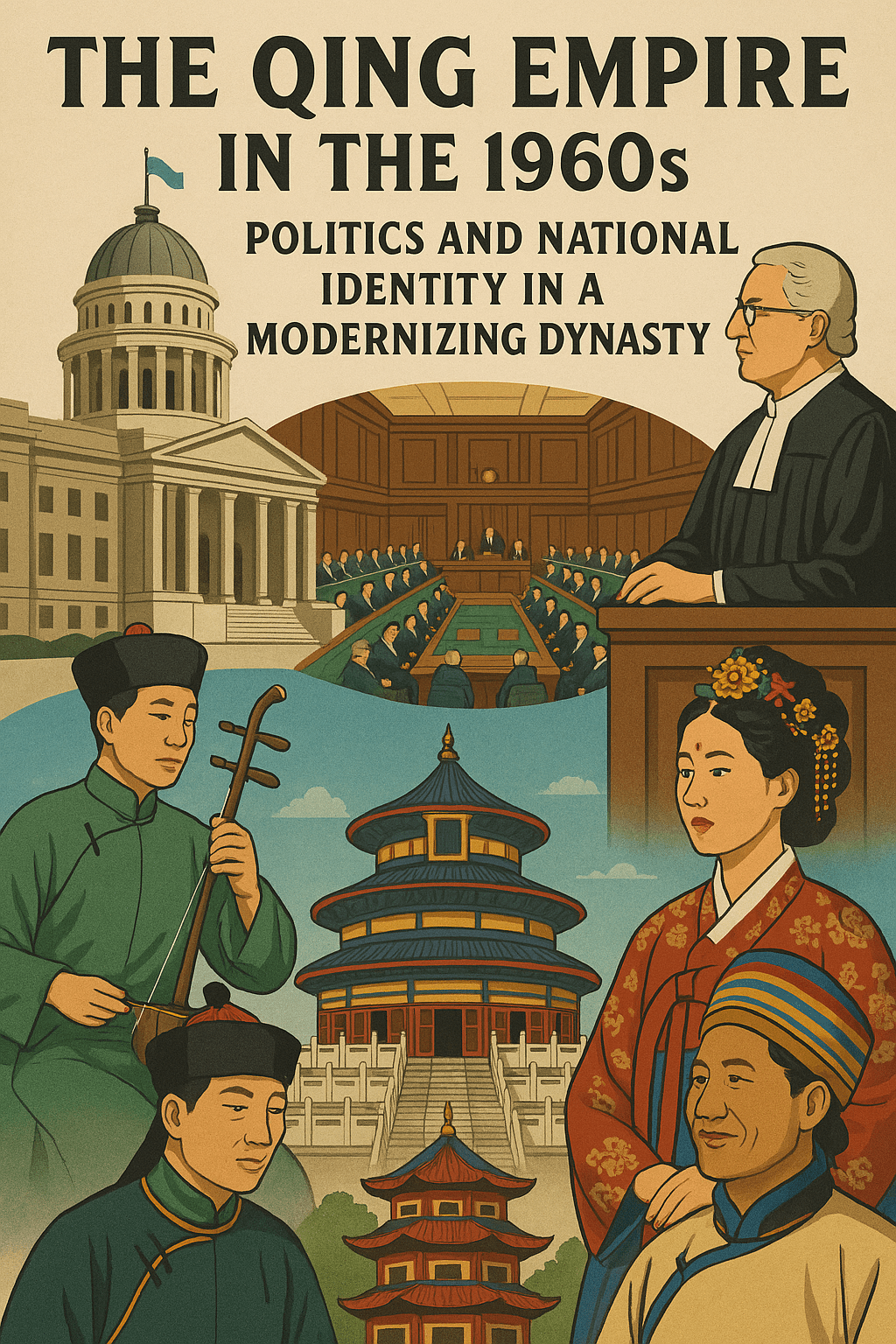

By the 1960s, the Qing Empire had successfully transformed itself into a modern constitutional monarchy, deftly balancing the legacy of imperial rule with the realities of democratic governance and the pressures of the Cold War. Politically stable and economically ambitious, the empire was marked by a rich cultural renaissance and an inclusive national identity that emphasized unity among its diverse ethnic groups. At its core, this period was defined by the coexistence of tradition and progress, embodied in the symbolism of the monarchy, the institutions of government, and the shared vision of a rising global China.

1. The Role of the Emperor: Symbol, Mediator, and Cultural Anchor

The Xuantong Emperor (Puyi), now in his mid-60s, was widely respected as a ceremonial figurehead who unified the nation through symbolic leadership. While his political power was limited, his influence on national consciousness was immense.

- Ceremonial Duties: He represented China in diplomatic affairs, opened sessions of the National Assembly, and gave national addresses that emphasized Confucian values and Chinese identity.

- Soft Power and Mediation: The Emperor often mediated between political factions and played a critical role during moments of national debate, lending moral authority to government decisions.

- Succession Planning: The Aisin Gioro family groomed younger members in diplomacy, governance, and sciences, ensuring the continuity of the monarchy.

2. The Guomin Yuan: Functional Democracy within Imperial Framework

The National Assembly, or Guomin Yuan, operated as a mature bicameral legislature, made up of the Renmin Yuan (People’s Assembly) and the Zhongyang Yuan (Central Assembly).

- Lower House: Directly elected by universal suffrage, with representatives from all provinces and social classes.

- Upper House: Included appointed representatives from the Imperial Household, religious leaders, ethnic minorities, and professional guilds.

Key Political Parties:

- Reformist Party (Gaige Dang): Dominant pro-monarchy moderates focused on social reform and modernization.

- Nationalist Party (Minzu Dang): Opposition party pushing for expanded democracy.

- Conservative Party (Bao Shou Dang): Represented traditionalists and rural elites.

- Socialist Alliance (Shehui Zhuyi Tongmeng): Advocated for social welfare and worker protections.

Coalition governments ensured cooperation and compromise.

3. Prime Minister and Cabinet: Efficient Governance

The Prime Minister, elected by the lower house, was the head of government. This position was supported by a Cabinet of technocrats and experts in:

- Foreign Affairs

- Defense

- Commerce and Industry

- Education and Culture

- Rural Development

The Prime Minister’s close collaboration with the Emperor symbolized the harmony between modern governance and imperial continuity.

4. Provincial Autonomy and Ethnic Inclusion

The Qing Empire’s vastness required localized governance:

- Provincial Assemblies: Managed budgets, education, and infrastructure.

- Ethnic Autonomy: Tibet, Xinjiang, and Mongolia operated under the Cultural Autonomy Framework, retaining their traditions and local leadership within Qing sovereignty.

Local councils handled municipal affairs, giving grassroots communities a voice in governance.

5. Judiciary: Legal Modernization with Confucian Roots

An independent judiciary upheld rule of law:

- Supreme Court: Oversaw constitutional issues.

- Regional and Local Courts: Handled civil and criminal cases.

- Ethnic Courts: Addressed cases within local religious and cultural norms.

Anti-corruption reforms in the 1950s had increased public trust in the legal system.

6. Managing Manchu-Han Relations: From Imperial Divide to National Unity

Ethnic tensions, particularly between Han and Manchu, were a historical legacy that the Qing Empire systematically addressed through reforms and cultural integration.

- Equal Representation: The Guomin Yuan included both Han and Manchu voices. Manchu privileges were abolished, and a meritocratic system ensured fair participation.

- Cultural Blending: Education systems taught both Confucian and Manchu traditions. National festivals incorporated multiethnic heritage.

- Preserving Manchu Identity: Language preservation programs, festivals, and museum initiatives ensured that Manchu heritage remained vibrant.

- Military Integration: The modern Imperial Armed Forces recruited from all ethnic groups. Service fostered unity and pride across regions.

- Economic Investment in Manchuria: Industrial hubs in Harbin and Shenyang became symbols of shared economic prosperity.

7. Cultural Renaissance and Civic Nationalism

The 1960s witnessed a vibrant cultural scene:

- Cinema and Literature: Flourishing artistic output that blended traditional aesthetics with contemporary themes.

- Architecture: Urban spaces reflected a hybrid of modern and classical Chinese design.

- Education and Literacy: Near-universal literacy and world-class universities contributed to a dynamic intellectual climate.

Women’s rights advanced steadily. By the 1960s, women held positions in government, education, and commerce, and made up 20% of the National Assembly.

8. National Symbols and Shared Identity

The monarchy functioned as a powerful cultural institution that unified the nation:

- National Celebrations: Events like Constitution Day and the Emperor’s Birthday reinforced loyalty to both the state and its traditions.

- Pan-Ethnic Identity: Government narratives framed the Qing dynasty as a shared legacy of all ethnicities in China.

Conclusion

By the 1960s, the Qing Empire had matured into a model of constitutional monarchy: culturally grounded, politically inclusive, and globally respected. Its ability to integrate tradition with modernity, and to resolve ethnic and social tensions through reform rather than revolution, set it apart in a world fractured by ideological conflict. In this alternate history, the Qing stands not as a relic of the past, but as a living institution—adaptable, dignified, and confidently leading a united China into the future.

Leave a comment