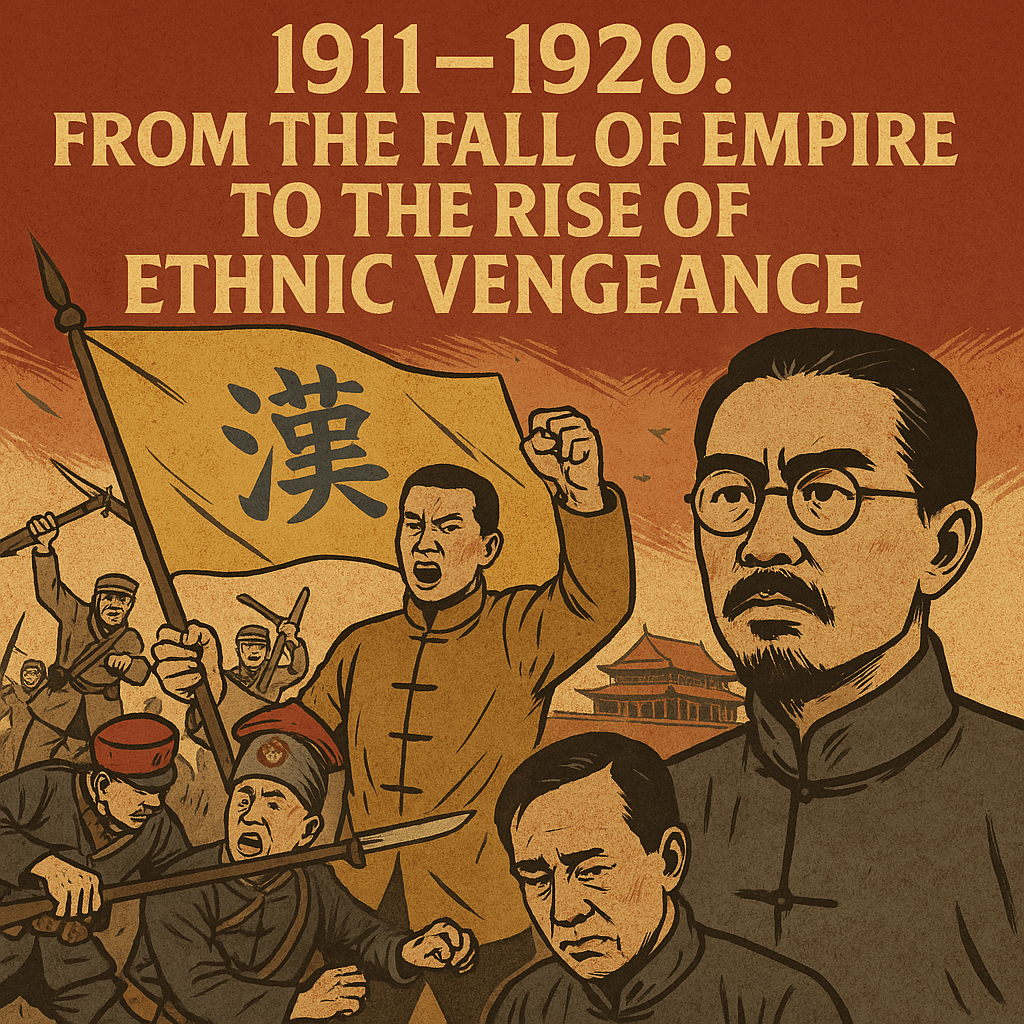

Point of Divergence:

In this timeline, the Xinhai Revolution of 1911, which led to the fall of the Qing Dynasty, takes on a much more radical and Han nationalist character. This divergence occurs when the revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen aligns his movement with “皇汉” (Huang-Han), or radical Han supremacist ideologies, instead of promoting his historical vision of a multi-ethnic and republican China. This shift is catalyzed by a combination of intense anti-Manchu propaganda, the weakening of the Qing dynasty, and key Han nationalist intellectuals taking leadership roles in revolutionary circles.

This divergence sees the Revolution transition from a primarily anti-monarchist uprising into a fervent ethnic and cultural crusade to restore China as a “Han-only” state, expelling or suppressing minority groups seen as remnants of “foreign domination.”

1911–1920: The Ascendancy of the Han Nationalist State

The Collapse of the Qing Dynasty

By 1911, the Qing dynasty, already weakened by decades of internal unrest, foreign incursions, and corruption, begins to face an even more organized and fanatical revolution. Unlike in our timeline, where Sun Yat-sen and the Tongmenghui movement emphasize a vision of unity between China’s many ethnicities (Han, Manchu, Mongol, Tibetan, and Muslim), this revolution is explicitly anti-Manchu. The slogan of the movement becomes “驱逐鞑虏,恢复中华” (“Expel the Tartars, Restore China”), but now with an emphasis on ethnic purging.

Key leaders in this alternate revolution include Zhang Binglin, an influential Han nationalist thinker, who plays a larger role in spreading anti-Manchu ideology. Revolutionary cells in provinces like Guangdong, Hunan, and Hubei ignite uprisings not just against Qing officials, but also against ordinary Manchu civilians. Violence spreads as mobs target Manchu garrisons and bannermen communities. Ethnic cleansing begins to occur in cities like Wuhan and Nanjing, where Manchu populations are expelled or massacred.

By February 1912, Emperor Puyi is forced to abdicate, but instead of being treated with respect (as in our timeline), the imperial family is immediately targeted by the Huang-Han radicals. The Forbidden City is stormed, and prominent Manchu aristocrats, including the regent Prince Chun, are executed. The royal family barely escapes; Puyi and a few loyalists are smuggled to Mongolia by remnants of the Eight Banners.

The Founding of the Han Republic

The Provisional Government of the Republic of China is declared in Nanjing in 1912, with Sun Yat-sen as its first president. However, the government rapidly adopts Han supremacist policies, alienating many of the minority groups who had supported the revolution. The new Republic officially declares itself the Han Republic of China (汉民共和国), and policies are implemented to eliminate or suppress the influence of “foreign” elements.

- Expulsion and Suppression of Minorities: The Manchu population is forcibly expelled from urban centers or killed outright. Mongols, Tibetans, and Uyghurs face intense persecution as well, though in remote areas like Tibet and Xinjiang, this sparks widespread resistance.

- Cultural Hanification: The government embarks on a campaign to enforce Han cultural practices across the former Qing territories. Non-Han languages are banned in schools and public life, and Confucianism is re-emphasized as a state ideology, replacing Sun Yat-sen’s historical adherence to Western-inspired republican ideals.

- Anti-Foreign Sentiment: The Han nationalist government begins to reject “Westernization” as a corrupting influence, while still adopting Western technology and military practices. Missionaries and foreign diplomats face increased hostility, and the foreign concessions in Shanghai and elsewhere come under attack.

The Warlord Era Turns Ethnic

As in our timeline, the collapse of central authority in Beijing leads to the rise of regional warlords. However, in this alternate history, many of these warlords align themselves with either the Han nationalist ideology or resistance movements among minorities.

- Southern Han Supremacy: The southern provinces, including Guangdong and Guangxi, remain strongholds of Huang-Han ideology. Leaders like Chen Jiongming emerge as staunch advocates of a “pure” Han China.

- Minority Resistance Movements: The Mongols, under the leadership of Bogd Khan, declare independence and ally with Tsarist Russian forces fleeing the Bolsheviks. Tibet declares independence under the 13th Dalai Lama, but finds itself under constant attack by Han nationalist militias.

- Hanification of the North: In northern China, former Manchu territories are torn apart by ethnic conflict. Han settlers, supported by the central government, begin moving into Manchu and Mongol lands, sparking fierce guerrilla resistance.

Foreign Relations and International Implications

- Japan’s Opportunism: Japan, recognizing the chaos in China, begins expanding its influence in Manchuria. However, instead of facing widespread resistance as in our timeline, Japan finds some allies among the Manchu remnants and minority groups who seek protection from Han nationalist persecution.

- Western Powers Alarmed: The United States, Britain, and France, initially supportive of the revolution against the Qing, grow wary of the Han nationalist regime. Reports of atrocities against minorities begin to circulate, straining diplomatic relations.

- Soviet Intrigue: The nascent Soviet Union sees the ethnic tensions in China as an opportunity to spread communist ideology, particularly among the oppressed minorities. Communist cells begin forming among Uyghur and Mongol populations, setting the stage for future conflicts.

The Rise of Radical Han Nationalism

By 1920, the Han Republic is consolidating its power. A new constitution is written that explicitly declares China to be a state of and for the Han people. Sun Yat-sen, increasingly sidelined by hardliners, resigns in frustration. Zhang Binglin, now one of the most powerful figures in the government, declares that the Han race must “reclaim its destiny” and rebuild a “pure” Chinese civilization. Political purges target moderates and reformers, while a massive propaganda campaign glorifies the ancient Han dynasty as the ideal model for the future.

The Huang-Han regime’s policies sow seeds of long-term instability, as the minorities on the periphery of the former Qing Empire grow increasingly defiant. In the north, Japanese-backed Manchu forces rally for a counteroffensive, while in the west, Muslim and Tibetan insurgencies gain momentum. China, though nominally unified, stands on the brink of internal collapse and external invasion.

Leave a comment