I.

I was twenty-one when I met John Lennon.

We were in a borrowed flat in Haidian, not far from the university. The air smelled like ink and dust, and there were eight of us crammed into a living room meant for two. We had one old speaker playing Double Fantasy on loop, half the lyrics scrawled into our notebooks, translated line by line, as if they were secret scriptures.

He arrived just past midnight.

I had smuggled him in through a back alley with two other students acting like decoys. The guards barely looked at us—they had no reason to. To them, we were just more kids chasing some Western fad. But inside, I was shaking. Not from fear.

From the impossible fact that he was actually here.

II.

Lennon didn’t act like a rock star. No sunglasses. No entourage. Just a long coat, a scarf, and a tired smile.

“You Zhang?” he asked.

I said yes, though my mouth barely worked. He shook my hand like I was his equal.

He looked around the room, at the girls with their makeshift typewriters, the boys with faded Che Guevara pins, the copy of Imagine we kept hidden in a thermos to avoid confiscation.

“You lot,” he said, “you’re beautiful.”

One of the students started to cry. Another offered him tea. He took it.

We talked for maybe two hours. About hope. About fear. About what it meant to want a voice in a place that refused to hear.

“Your courage,” he told us, “makes our shouting look like whispering.”

III.

Before he left, I asked him if he would sing something.

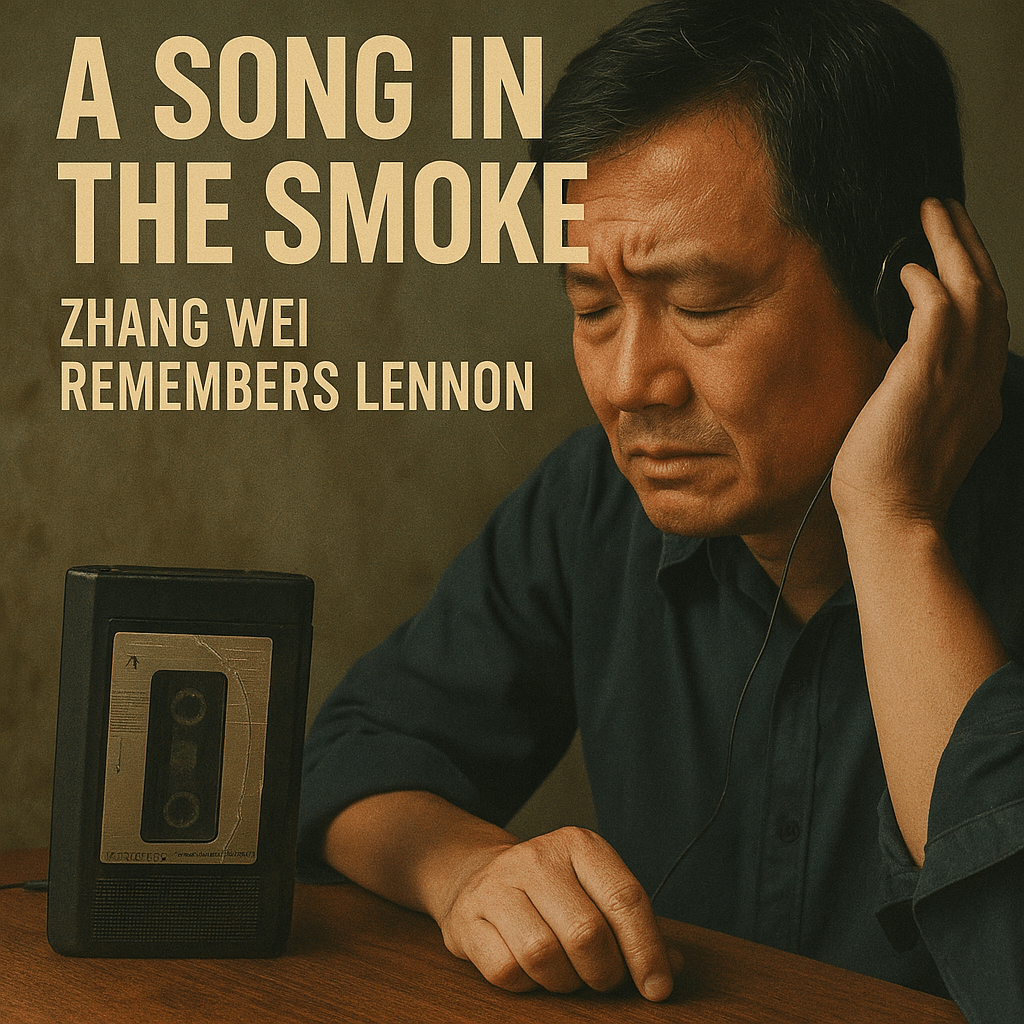

We didn’t have a guitar. Just a broken harmonica and a cheap cassette recorder.

He chuckled and said, “Bugger it,” and sang Imagine a cappella.

Soft. Barely above a whisper. We sat in silence, listening like it was the last sound we’d ever hear.

I still have the tape. Warped. Fuzzy. But it’s real.

And it’s mine.

IV.

Three months later, the square was soaked in blood.

They crushed us.

Not just with bullets.

With silence.

With forgetting.

Some of my friends disappeared. Some reappeared, changed. I was lucky. I ran fast, and I ran far. I never saw Lennon again.

He spoke out, of course. I read the articles years later. He called us brave. He said our song would echo.

But in Beijing, there was only silence.

V.

In 1994, I moved to Shenzhen.

I told people I was from the north, that I had studied engineering, that I liked American music. But I never told them about the night with Lennon. Not once.

I met my wife in a factory cafeteria. She thought I was boring, but dependable. We married, raised two kids. Life became a routine of clocks and bills and queueing for rice.

And I told myself the movement was dead.

We lost.

VI.

Now I am 50.

My son is seventeen. He found the old tape in a box last year—hidden behind tax documents and faded books.

He put it in the player and pressed play.

At first, it was static. Then that voice.

“Imagine there’s no heaven…”

I turned away before he could see the tears.

But they came, as they always do.

Because in that moment, I wasn’t a middle-aged man in a two-room apartment with back pain and a mortgage.

I was twenty-one again, sitting in a dim Beijing apartment, listening to John Lennon sing our song, just for us, just for that moment.

And I remembered:

I know who I am.

Not because the movement won.

But because it mattered.

Because we tried.

Because someone like John Lennon saw us—not as idealists, not as pawns.

As people. As equals. As dreamers.

And every time my son plays that tape, I know the dream never fully died.

Not while the music still plays.

Leave a comment