A short story set in the alternate history timeline, featuring Jean-Paul Sartre

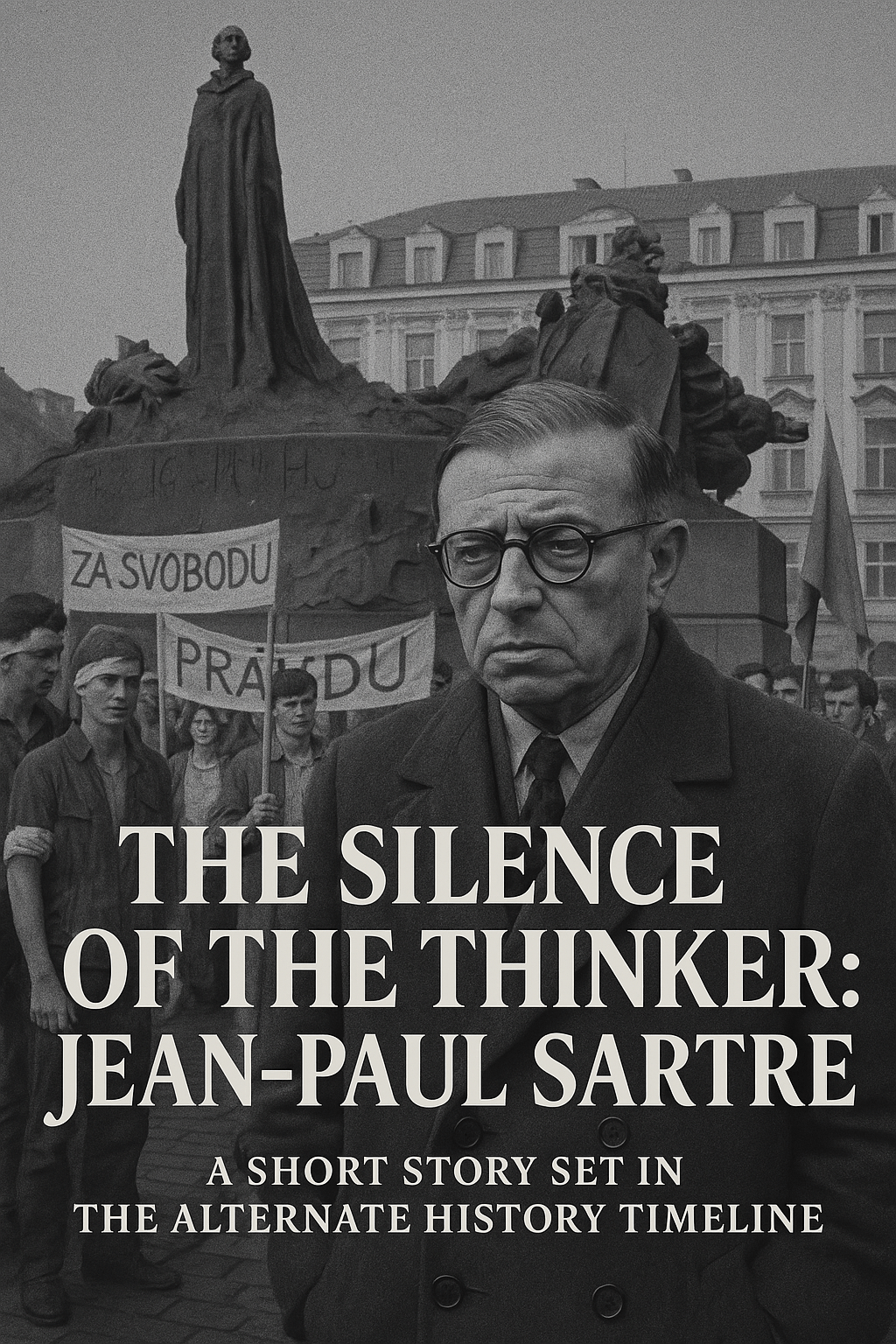

He stood in the square beneath the statue of Jan Hus, the old reformer defiant on his pedestal. Around Sartre, the square pulsed with youth—Czech students with bandaged arms, hastily painted banners, and voices hoarse from nights without sleep.

For Jean-Paul Sartre, exile had become a slow-burning crucible. Twelve years earlier, in 1956, he had boarded a train from Paris to East Berlin, flanked by cameras, anti-Gaullist slogans, and quiet tears from Simone de Beauvoir. In defiance of NATO hypocrisy, he declared, “If the workers’ state is imperfect, then so am I. Better an imperfect struggle than the perfect lie.”

He had believed it. Or needed to.

Berlin, 1956–1961: A Philosopher Among Apparatchiks

East Berlin did not know what to make of him. The functionaries at Humboldt University nodded politely at his lectures, then filed reports behind closed doors. Sartre found his brand of liberal existentialism—anchored in individual freedom and self-definition—met with bureaucratic frost.

He had expected ideological scrutiny. What surprised him was the emptiness—a gray conformity that even Camus, his old rival, hadn’t quite warned him of.

The students listened, yes—but they asked no questions.

He was given an office. Then a minder. Then, in 1959, restrictions on travel. By 1960, Sartre’s works were quietly removed from university reading lists, replaced by Lukács, Lenin, and party-approved dialecticians.

He’d tried adapting: more Marx, less Kierkegaard. He wrote essays titled Freedom Within the Party, but they gathered dust. He submitted a critique of East German censorship to Neues Deutschland in 1961—it was rejected without reply.

When Khrushchev fell in ’64, Sartre’s brief window of reformist hope snapped shut.

Moscow, 1965: The Quiet Condemnation

They summoned him to Moscow for a “friendly consultation.” There, a polite Soviet academic told him, over samovar tea, that his continued emphasis on the “bourgeois self” was counter-revolutionary. “Comrade Sartre, your Parisian liberalism undermines proletarian unity.”

He returned to East Berlin in silence.

Simone had begged him, in her letters smuggled from France, to come home. “They cannot own your mind, Jean-Paul. Let them disown your body.”

But the exile was too public, too symbolic. He was no Solzhenitsyn—they would not banish him westward in protest. And he, stubborn, would not admit defeat.

Prague, 1968: Spring in Bloom, Then Blood

So when word came in early ’68 of reformists in Prague—of Alexander Dubček’s promise of “socialism with a human face”—Sartre saw, perhaps naively, his last chance.

He crossed into Czechoslovakia in March, invited by Charles University reformists and writers who still read Being and Nothingness in mimeographed French.

Here were students who debated freely. Here were cafes like Paris. Here, Sartre felt for the first time in over a decade that his mind was not a liability.

He gave lectures on personal freedom, on moral choice within socialism. He warned gently, diplomatically, that reform must come from within. And yet, his eyes burned again with the intensity of 1940s Montparnasse. He was needed, and he needed to matter.

Dubček met with him privately in May. “Comrade Sartre, you have given our students courage. And that may be more than guns.”

August 21, 1968: The Night of Tanks

He woke to distant rumbling.

By morning, Soviet tanks rolled down Wenceslas Square. Protesters screamed, flung Molotovs. Gunfire answered.

Sartre, 63 and weak from years of cigarettes and bad winters, stood at the university steps as soldiers stormed inside. A Czech professor pulled him aside.

“They’ll arrest you. You must flee.”

“I have fled enough,” Sartre murmured.

By nightfall, radio towers were silenced. The student movement was crushed. Dubček disappeared.

The End

Sartre was arrested by the KGB the following week. The French government, embarrassed but pressured by public outcry, demanded his release.

Moscow, in a final gesture of contempt, denied his exile status altogether, calling him an “internal figure of the Socialist Bloc.” He was quietly moved to a sanitarium outside Prague.

On November 2, 1968, Jean-Paul Sartre died of heart failure.

Officially, it was natural causes.

Unofficially, students whispered he’d starved himself to death.

Aftermath and Legacy

In the West, protests erupted across university campuses. Posters with Sartre’s face—eyes shadowed, lips tight—appeared alongside slogans:

“He Died for Your Freedom.”

“You Gave Him to Them.”

In the East, his books were banned. His name struck from records. It would take until the fall of the Berlin Wall for Sartre’s time in exile to be publicly discussed.

The irony haunted both worlds: a man who wrote endlessly of freedom, exiled to a world where freedom was punished—and who, in the end, could neither escape nor change it.

Leave a comment