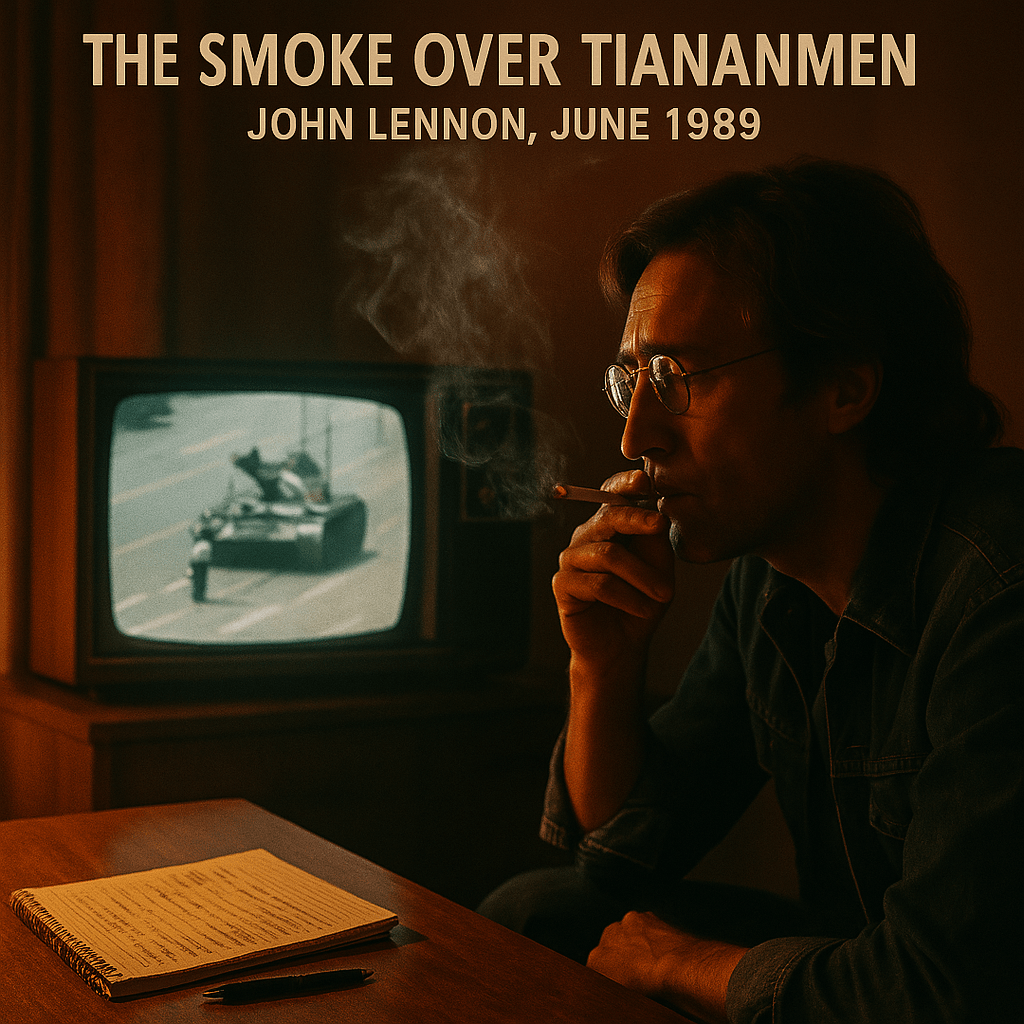

June 4, 1989

New York City, 3:10 AM

Television flickering. Cigarette burning low. A silence too loud to bear.

I.

I couldn’t sleep.

I hadn’t really slept since I left Beijing.

That place stayed with me. Not the architecture. Not the rehearsed smiles of officials. The people. The students. Those wild-eyed kids with notebooks in one hand and dreams in the other. They reminded me of us, back in ’68—only braver. We never stared down tanks.

And now, I was staring at one.

On my TV.

II.

I remember the square—not as it looked on TV, but as I walked it that night in March. Quiet, half-lit, full of whispers. I was smuggled in by a kid named Zhang Wei. He couldn’t have been older than Sean. He wanted to talk about Lennon and Lenin. Said I’d taught him about freedom without a single ideology.

“You make revolution feel human,” he said.

I didn’t know what to say to that. I just shook his hand.

I saw his face again tonight, in the crowd on the screen.

Maybe it was him. Maybe not. But the face had that same intensity—that belief that change was not just possible, but necessary.

III.

And then the screen flickered.

And the tanks came.

I dropped the cigarette.

A boy stood in front of one.

Just… stood. Like a bloody lighthouse in a storm of steel.

The tank stopped.

For a second, I thought: This is it. The world changes here.

But the tank moved. The cameras cut.

Then came the gunshots.

Not movie sound. Not soundtrack.

Real.

I sat frozen, like I’d swallowed glass.

Yoko called my name, but I didn’t answer.

They were shooting the dream. Again.

IV.

They said later the government called them “rioters.”

Said they were “destabilizing society.”

The same words every tyrant uses when people dare to speak.

I wanted to scream. I wanted to fly back to Beijing, grab a guitar, and stand in that square until they shot me too. But what would that have done? What could I do?

I turned the TV off. I turned it back on. I paced. I wept. I wrote.

I wrote a song that night called Smoke Over Tiananmen.

No melody yet. Just words.

“You can shoot the singer, but the song will remain

And the echo of footsteps will carry their name

Through smoke and silence, they still demand

A voice, a vote, a promised land.”

V.

People said later I should’ve stayed quiet. That China was “complicated.”

That I was meddling.

To hell with that.

I stood in that square. I talked to those kids. I saw their faces.

If I don’t speak for them, who will?

VI.

In the years that followed, I never went back.

They wouldn’t let me.

But my voice did.

Bootlegs. Banned songs. Whispered lyrics behind closed doors.

“Imagine” scratched onto chalkboards before teachers erased it.

My name passed like contraband through corridors of fear.

I became a ghost in China.

But not a silent one.

VII.

June 4th never left me.

I think part of me stayed in that square—where the candles burned, and the students sang, and for one brief moment, the world felt like it could change.

And when the bullets fell, it was like watching a mirror shatter.

But here’s the truth I’ve learned:

You can crush a movement.

You can burn books, jail poets, ban songs.

But you can’t kill a dream once it’s been sung aloud.

And in Beijing, in 1989, the dream was sung.

Loud enough that I still hear it.

Leave a comment