The spring of 1989 was a season of hope and uncertainty in China. The country was undergoing profound transformations as it attempted to balance economic reforms initiated by Deng Xiaoping with the authoritarian grip of the Communist Party. Beneath the surface, however, a wave of dissent was building, fueled by intellectuals, students, and workers dissatisfied with corruption, lack of political freedoms, and growing inequality.

Into this volatile atmosphere stepped John Lennon.

The Invitation

In January 1989, Lennon received a letter from a coalition of Chinese dissident artists, musicians, and intellectuals who admired his music and activism. They described how songs like Imagine and Power to the People had inspired underground movements in China, giving hope to those pushing for political reform. The letter included a simple plea: “John, your voice can reach places our own voices cannot. Please come to China.”

The invitation piqued Lennon’s interest. Although he had always been outspoken about issues in the West—Vietnam, gun violence, and nuclear disarmament—he had largely stayed out of direct critiques of China, a country shrouded in secrecy for most Westerners. Now, in a rapidly changing world, the opportunity to bring his message of peace and freedom to China felt too important to pass up.

Despite Yoko Ono’s initial concerns about safety, Lennon accepted the invitation. Working through unofficial channels, he secured approval from the Chinese government to visit as a “cultural ambassador,” though he knew his visit would be heavily monitored.

Arrival in Beijing: March 1989

Lennon landed in Beijing on March 15, 1989, greeted by a crowd of Chinese fans and curious onlookers. His fame had long since crossed borders, and despite government efforts to censor Western pop culture, bootlegged Beatles albums and Lennon’s solo works were widely circulated among Chinese youth. To many, he was more than a musician—he was a symbol of freedom and rebellion.

The Chinese government was nervous about Lennon’s visit. While officials had approved it as a cultural event, they worried that his reputation as a political agitator might embolden the growing pro-democracy movement. To minimize risks, they restricted his itinerary, assigned him government minders, and insisted that he avoid public commentary on political issues.

Lennon, of course, had other plans.

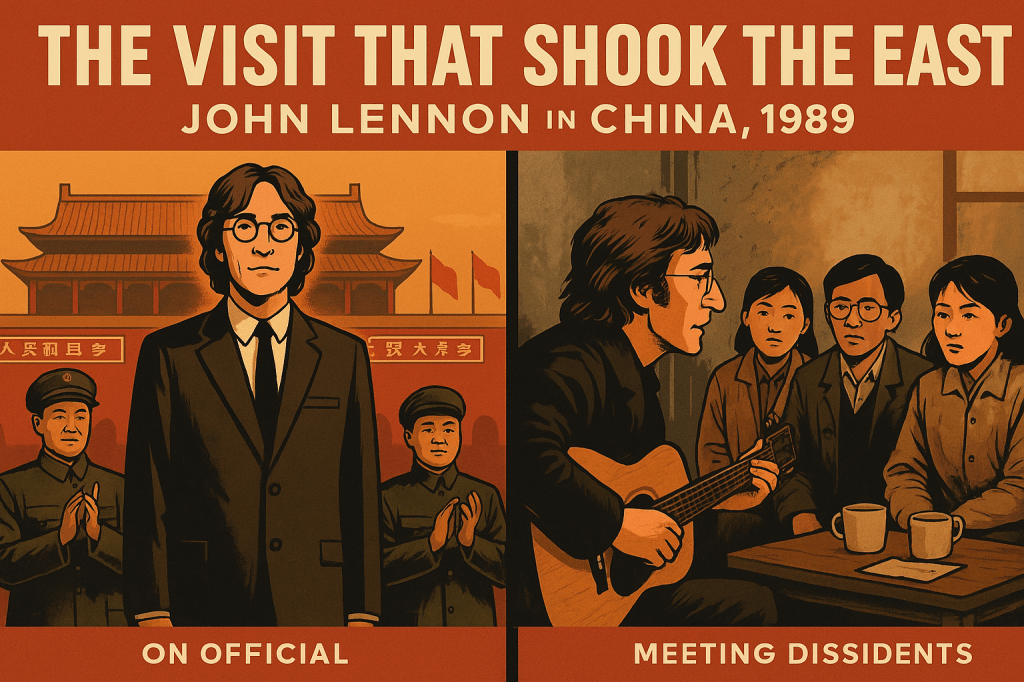

The “Official” Agenda

Over the first few days, Lennon attended tightly controlled events designed to showcase China’s cultural achievements. He visited the Forbidden City, the Great Wall, and the Summer Palace, always flanked by government officials and media crews. At every turn, Lennon played the part of the respectful visitor, smiling for cameras and offering diplomatic platitudes. To the press, he spoke about the beauty of Chinese culture, the talent of its people, and his hope for global peace.

But behind closed doors, Lennon sought out opportunities to meet with ordinary Chinese citizens—particularly the artists, students, and intellectuals who had invited him. These unofficial meetings were coordinated in secret, often under the noses of his government minders.

The Secret Meetings

One of the most pivotal moments of Lennon’s visit occurred on the night of March 20, when he slipped away from his hotel under the cover of darkness. Through contacts arranged by a young dissident artist named Liu Xiaofan, Lennon was taken to a small gathering in a nondescript apartment on the outskirts of Beijing. There, he met with a group of student leaders and underground musicians who had been instrumental in organizing pro-democracy protests.

The atmosphere in the room was electric. For many of the young activists, meeting Lennon felt like a dream. He listened intently as they spoke about their struggles—corruption in the government, the lack of freedom of speech, and the widening gap between the rich and poor. One student leader, a 21-year-old named Zhang Wei, described how Lennon’s songs had been smuggled into China on cassette tapes and passed around among friends. “Your music taught us to dream,” Zhang said. “It taught us to imagine a different world.”

Lennon, visibly moved, responded with humility. “I’m just a bloke with a guitar,” he said. “The real power’s in you lot—you’re the ones out there putting yourselves on the line.”

Before leaving the meeting, Lennon performed an impromptu acoustic version of “Imagine.” The room fell silent as his voice echoed through the cramped apartment. Some of the students quietly wept. Zhang later described it as “the moment we truly believed change was possible.”

The Press Conference

On March 23, the final day of Lennon’s official visit, he held a press conference in Beijing. Government officials had strictly outlined what he could and could not say, but Lennon found subtle ways to convey his message. When asked about his impressions of China, he praised the creativity and resilience of its people. “I think the future belongs to the young,” he said. “They’re the ones who will decide what kind of world they want to live in.”

One reporter asked him if he had any advice for Chinese youth. Lennon paused for a moment, then smiled. “Keep dreaming,” he said. “The world needs dreamers more than ever.”

While his comments were ambiguous enough to avoid outright censorship, their true meaning was not lost on those paying attention. To many young Chinese, it was a call to action.

The Aftermath

Lennon left China on March 24, but the impact of his visit lingered. His subtle encouragement of the pro-democracy movement inspired a wave of optimism among students and activists, many of whom carried his words and music into the streets during the Tiananmen Square protests just weeks later. Bootleg recordings of his press conference and his acoustic performance of “Imagine” spread like wildfire, becoming rallying cries for the movement.

The Chinese government, however, was less enthusiastic about Lennon’s visit. State media initially praised him as a cultural icon, but after the Tiananmen Square crackdown in June, they retroactively condemned him as a dangerous influence. Privately, government officials acknowledged that Lennon’s visit had emboldened the protesters, though they insisted it was only a minor factor in the larger uprising.

For Lennon, the events in China weighed heavily on his heart. He publicly condemned the government’s violent response to the protests, calling it “a crime against humanity.” In the years that followed, he continued to speak out for Chinese democracy, dedicating songs and benefits to the cause.

Legacy of the Visit

Lennon’s visit to China in 1989 became one of the most controversial and impactful moments of his post-Beatles career. Though his time in the country was brief, his influence on the pro-democracy movement was profound. To this day, many Chinese dissidents remember Lennon not just as a musician, but as a symbol of hope and resistance.

Leave a comment