Here is a fictionalized personal account from a member of Jeunesse Révolutionnaire Sartre, the radical student group that publicly humiliated Simone de Beauvoir in 1971. Soon after, they became the first collective exiled under the “Welcome to Leave” policy—a twisted gesture from the French government designed to be both punishment and propaganda.

This account follows Claire Aubanel, a 22-year-old Sorbonne student, tracing her journey from revolutionary idealism to painful reckoning.

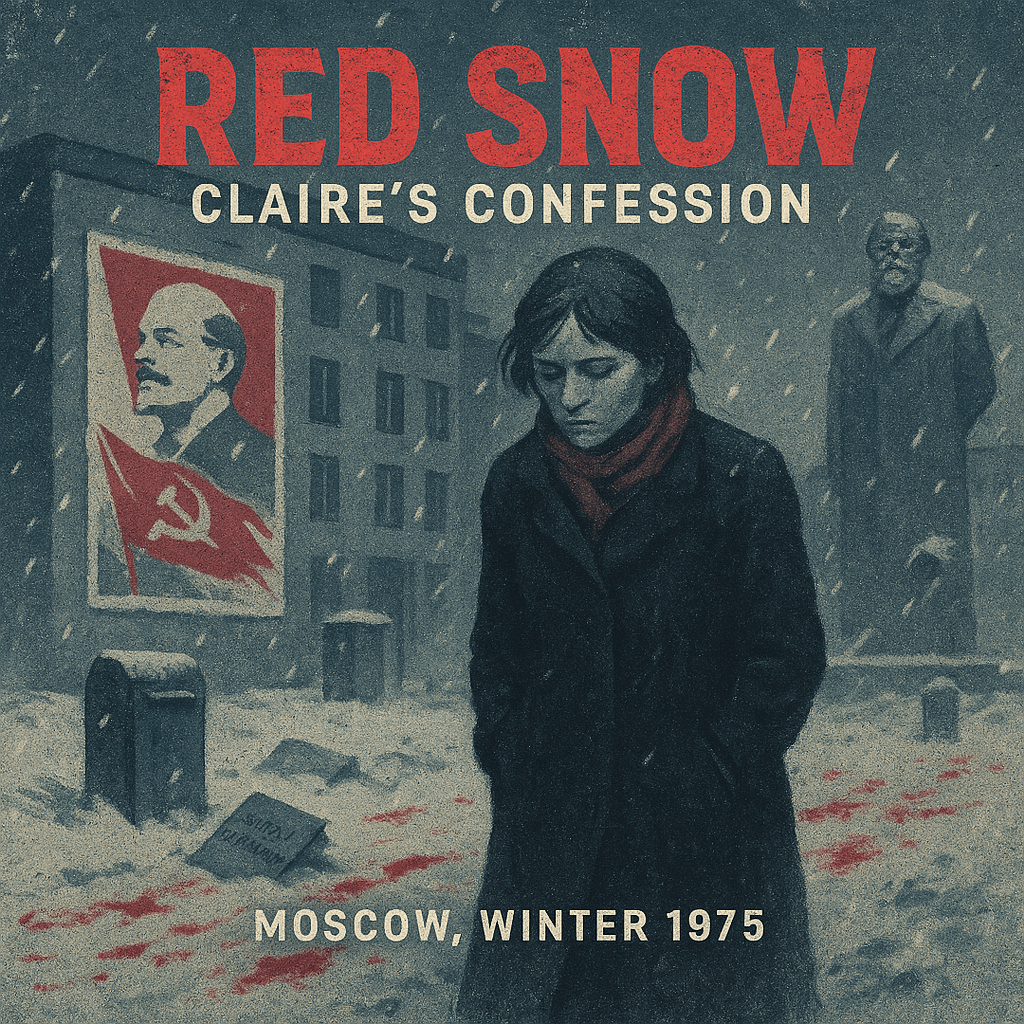

Moscow, Winter 1975

Translated from unpublished French memoir fragments, found in a Moscow archive in 1992

We were thrilled. God, it’s so hard to say now—but we were thrilled.

When the summons came, a letter on crisp government stationery, we read it aloud in our shared apartment in the Latin Quarter like it was a ticket to paradise.

“Given your stated ideological commitments, the French Republic gladly facilitates your transition to permanent academic and civic residence in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Welcome to Leave.”

We laughed. We cheered. Welcome to Leave! It sounded like victory—like irony, like rebellion consecrated by the very enemy we had fought on cobblestones and lecture halls.

There were ten of us. All philosophy students. All intoxicated by Sartre, by Fanon, by Marcuse, by barricades and Molotov cocktails and the thrill of becoming history.

Simone de Beauvoir had just published her memoir about Sartre’s “suffering.” We mocked it. “A bourgeois melodrama,” Camille said. “She wanted to turn him into a housepet of the West.” We believed that. We needed to.

Moscow, 1972: The Arrival

They met us at Sheremetyevo Airport with flowers and applause. Soviet youth leaders with pinched smiles and memorized French. We were guests of honor. Toasts were made.

To the brave revolutionaries of France!

At first, it was intoxicating.

We were given student housing near the Patrice Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University, a new international campus meant to foster Third World solidarity. We drank vodka on the rooftop and shouted Maoist slogans at the winter stars. We smoked Algerian cigarettes and read Das Kapital like scripture. We slept with each other and made manifestos before dawn.

The world was changing, and we were part of it.

1973: The Drift

It started slowly.

The Soviet students—at first curious—grew distant. They called us “theaters of protest,” “bourgeois play-actors.”

I tried to organize a reading group on Being and Nothingness. Only two Russians came. One left early. The other told me in halting French:

“You talk of choice like you own it. We do not own anything.”

We were labeled liberal romantics by Party youth officials—“formalist,” “impractical,” “emotionally unstable.” Some of our lectures were canceled. We were allowed to attend classes, but not lead them.

Camille was removed from the Party-affiliated film program after submitting a script about worker alienation in a tractor factory. “Too Western,” they said. She cried in the bathroom for three days.

1974: The Realization

In February, a Ukrainian roommate named Oksana whispered to me in the dormitory corridor:

“You think you are dangerous because you shout. But danger here wears a different face. It is the silence that kills.”

That night, I reread Simone de Beauvoir’s memoir, smuggled in by a visiting Yugoslav. For the first time, I understood what she had meant.

The silence here was not the silence of peace—it was the silence of exile within exile. Of knowing you are tolerated as a symbol, but never trusted as a soul.

1975: The Collapse

Camille slit her wrists in the dormitory bathtub.

Not deep. Not fatal. But enough.

She had received word her mother died. The French embassy refused to issue her a temporary visa. “Voluntary ideological exiles do not qualify for repatriation,” the letter said.

When I visited her in the sanitarium outside Moscow, she said:

“We were children, Claire. Playing with matches in a dry house. And now the house has burned, and we’re still pretending it’s warm.”

I have not written home in over a year.

I stopped calling myself a revolutionary two winters ago.

Now, I simply try to be quiet enough to be ignored. It is the safest way to survive.

Postscript

I do not hate Sartre anymore.

I do not hate Simone.

I hate the space between what we believed and what we became.

We came looking for the future—and found a mausoleum of old slogans.

And when I walk the icy streets of Moscow, watching the red flags flutter in the wind like tired ghosts, I whisper a prayer I no longer believe in:

Welcome to Leave.

Leave a comment