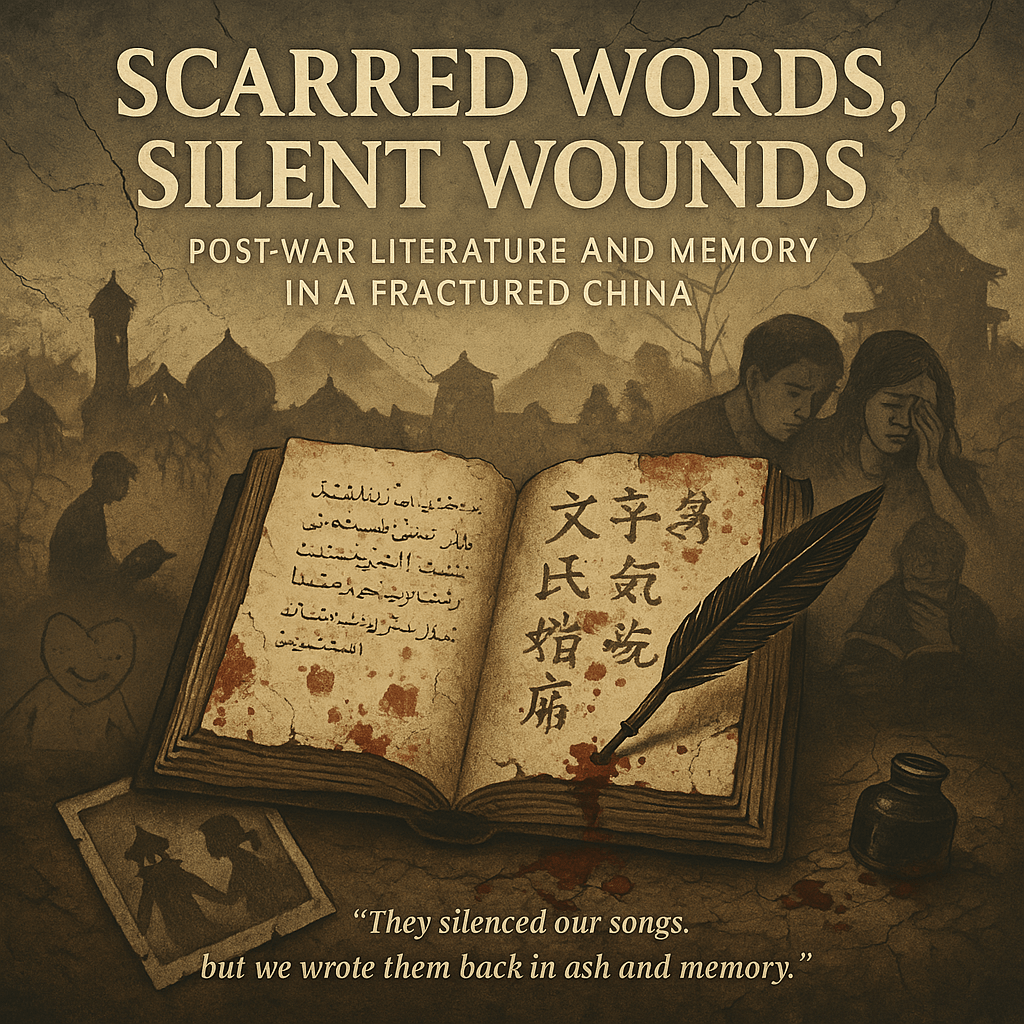

In the post-war era of this alternate timeline, a wave of literature emerges grappling with the trauma, repression, and legacy of the Huang-Han regime’s ethnonationalist policies, its collapse during the Second Sino-Japanese War, and the scars left on individuals, families, and entire communities. This body of literature, often referred to as “scarred memory literature” (创伤记忆文学), reflects the complex emotions of guilt, shame, loss, and reconciliation that haunt a society struggling to rebuild itself after years of genocide, war, and internal strife.

Themes in Scarred Memory Literature

- Ethnic Repression and Cultural Loss

- A central theme in post-war literature is the erasure of minority cultures under the Huang-Han regime. Writers from both minority and Han backgrounds explore the destruction of languages, traditions, and identities, and the devastating psychological toll this had on individuals.

- Common motifs include characters who lose their cultural roots, families torn apart by repression, and the recovery of forgotten or suppressed traditions.

- Example works often feature minority protagonists reflecting on the forced abandonment of their culture, such as the destruction of mosques, Tibetan monasteries, or Mongolian grazing lands.

- Identity Crisis and “Half-Blooded” Characters

- Mixed-ethnicity characters—like children of Han and minority parents—become recurring figures in scarred memory literature. These characters symbolize the fractured identity of post-war China: torn between the Huang-Han regime’s demand for Han purity and the reality of a multiethnic nation.

- Writers often explore how these individuals navigate their sense of belonging in a post-Huang-Han society, where resentment toward the regime creates new tensions, even among Han-majority populations.

- Survivor Guilt and the Complicity of the Han Majority

- Many post-war works delve into the moral and emotional struggles of ordinary Han citizens who participated in, witnessed, or were complicit in the regime’s atrocities. These stories explore questions of guilt, complicity, and redemption.

- Common narratives include Han citizens who regret their silence during the ethnic cleansing of minorities, or who secretly resisted but failed to make a difference. These stories often feature introspective, broken protagonists wrestling with their actions or inactions.

- Generational Trauma

- Stories often focus on how the trauma of the Huang-Han era is passed down to younger generations. Children and grandchildren struggle to understand the actions and beliefs of their parents, who lived through the regime’s propaganda and policies.

- A recurring theme is the discovery of “hidden truths,” as younger characters uncover the role their families played in the regime—whether as perpetrators, collaborators, or victims.

- Resistance, Rebellion, and Redemption

- While many works dwell on the despair of the Huang-Han era, others celebrate acts of resistance. These stories highlight the bravery of minorities, communists, and dissenting Han citizens who opposed the regime, often at great personal cost.

- Redemption arcs are common, with characters who initially supported the regime ultimately rejecting its ideology and making sacrifices to undo the harm they caused.

- Reconciliation and the Hope for Unity

- In the aftermath of the regime’s collapse, some works explore the difficult process of reconciliation between Han and minority communities. These stories emphasize the need for understanding and coexistence, even as the scars of the past linger.

Prominent Works of Scarred Memory Literature

1. 《消逝的家园》(Vanished Homeland) by Aisike (艾斯克)

- Author: A Uyghur writer exiled during the Huang-Han regime, Aisike returned to Xinjiang after the war to document the devastation wrought on his community.

- Plot: The novel follows a young Uyghur woman named Gulnisa, who returns to her hometown in southern Xinjiang after years in hiding, only to find it destroyed by forced relocations and assimilation policies. Haunted by memories of her family’s persecution, she begins to rebuild her life and rediscover her cultural roots, eventually becoming a leader in her community’s revival.

- Themes: Cultural erasure, resilience, and the search for belonging.

2. 《半个名字》(Half a Name) by Li Mingqi (李明启)

- Author: A fictionalized memoir written by a mixed-race Han-Manchu man who grew up during the Huang-Han regime (a continuation of the story of the character we previously explored).

- Plot: The narrator reflects on his childhood, torn between loyalty to his Han father and his Manchu mother, who was taken away by the regime. As an adult, he discovers suppressed documents revealing the truth about his mother’s fate in a labor camp, forcing him to confront the shame and guilt of denying his heritage during his youth.

- Themes: Identity, generational trauma, and the cost of silence.

3. 《焚毁的寺院》(The Burned Monastery) by Tsering Dorje (次仁多杰)

- Author: A Tibetan author who witnessed the destruction of his hometown’s monastery during the regime’s campaigns in the 1930s.

- Plot: Set in a remote Tibetan village, the story follows a young monk who survives the destruction of his monastery. He struggles to preserve sacred texts and teachings while reconciling his anger toward the Han soldiers who carried out the orders. In a climactic moment, he chooses forgiveness over revenge, seeking to rebuild cultural bridges after the war.

- Themes: Loss, forgiveness, and cultural survival.

4. 《他们的静默》(Their Silence) by Zhang Yuchen (张玉辰)

- Author: A Han intellectual who became critical of the Huang-Han regime after the war.

- Plot: The novel follows a group of Han intellectuals who were complicit in the regime’s propaganda efforts but secretly harbored doubts. Set in the post-war years, the story alternates between their wartime actions and their attempts to atone for their complicity by aiding in post-war reconciliation efforts with minority groups.

- Themes: Moral compromise, guilt, and redemption.

5. 《鸿沟》(The Chasm) by Zhou Xiaoping (周小平)

- Author: A Han journalist who covered the Huang-Han government’s collapse and its aftermath.

- Plot: A Han journalist travels to Inner Mongolia after the war to interview survivors of the regime’s policies. He meets a Mongolian herder whose family was killed during the forced relocations, and their dialogue forms the backbone of the novel. The story grapples with the “chasm” between Han and minority perspectives, and whether it can ever truly be bridged.

- Themes: Reconciliation, dialogue, and the weight of history.

Impact of Scarred Memory Literature

1. National Reckoning

These works play a critical role in fostering a national conversation about the horrors of the Huang-Han era. By highlighting the perspectives of both victims and perpetrators, they force readers to confront uncomfortable truths about their history.

2. Bridging Ethnic Divides

Many of these works emphasize the shared humanity of all ethnic groups, challenging the ethnonationalist ideology that drove the Huang-Han regime. They advocate for a multiethnic Chinese identity and celebrate the resilience of minority cultures.

3. Cultural Revival

In minority regions like Tibet, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia, literature becomes a key tool for preserving and reviving cultural traditions. Authors document oral histories, legends, and rituals that were nearly lost during the Huang-Han regime.

4. Political Sensitivities

While these works are celebrated in some circles, they are also controversial. In the post-war communist regime, some scarred memory literature faces censorship if it is seen as overly critical of central authority or too sympathetic to separatist movements.

Conclusion

Scarred memory literature in post-war China becomes a powerful medium for processing the trauma of the Huang-Han era. Through vivid storytelling and poignant themes, these works memorialize the suffering of minorities, examine the failures of ethnonationalism, and offer a vision of a more inclusive, united future. They serve as both a warning against the dangers of extremism and a testament to the resilience of human spirit in the face of oppression.

Leave a comment