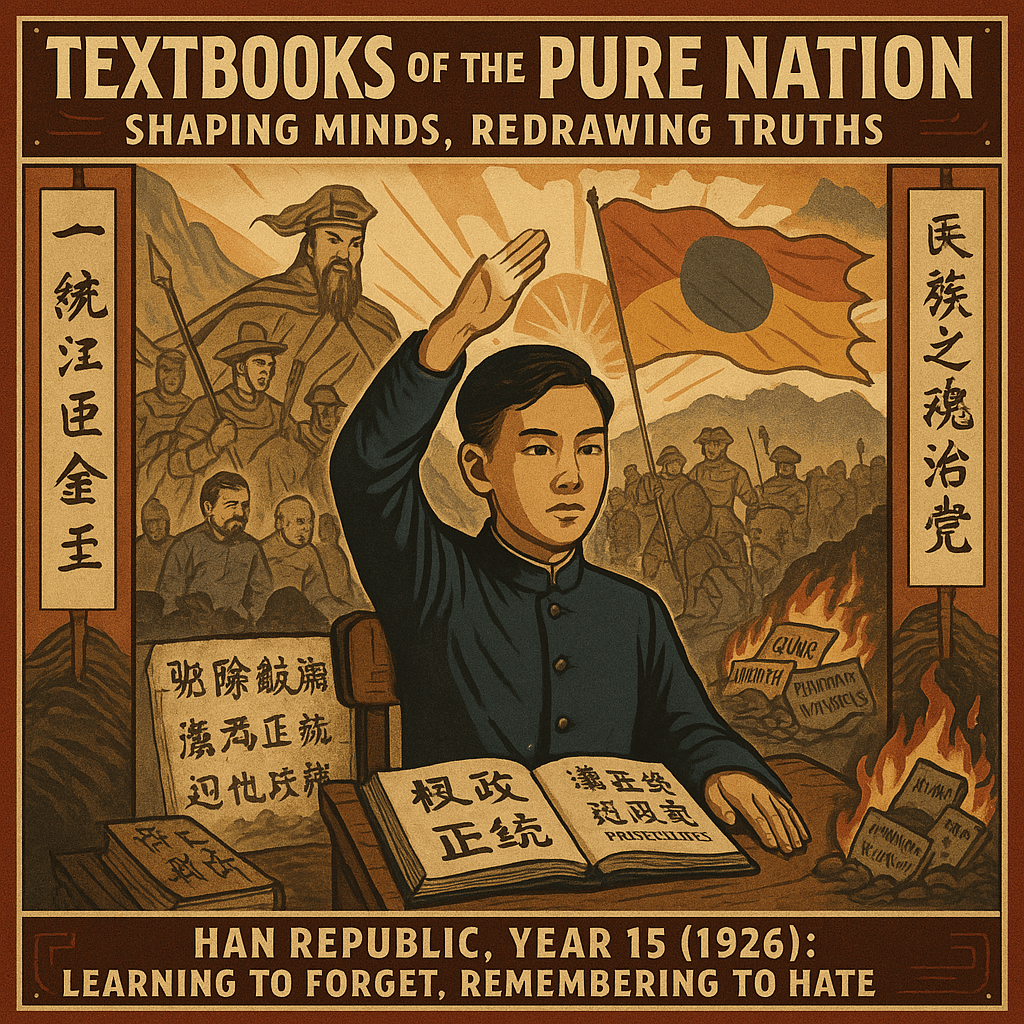

In this alternate timeline, where Han Nationalism has taken root following the 1911 Revolution, history textbooks in 1920s China reflect the ideological and cultural agenda of the Huang-Han (皇汉) regime. These textbooks are heavily influenced by the government’s ethnocentric policies, glorification of the Han people, and its rejection of “foreign” influences. They serve as a tool for nation-building, instilling a sense of ethnic pride among Han students while marginalizing the contributions of China’s minority groups.

Below are the major themes that dominate Chinese history education in the 1920s in this alternate history:

1. Glorification of the Han Race as the Core of Civilization

- Central Narrative: The history of China is redefined as the story of the Han people as the rightful rulers of the land, with all other ethnic groups framed as either barbarian invaders or peripheral actors. The curriculum lionizes the Han as the “purest and most advanced” civilization in East Asia, presenting them as the unbroken inheritors of Chinese culture.

- Mythical Beginnings: Emphasis is placed on ancient Han cultural heroes such as the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi) and Emperor Yao, who are described as the “founders of Chinese civilization.” These figures are framed as exclusively Han, erasing any suggestion of ethnic diversity in early China.

- The Han Golden Ages: Particular focus is given to the Han dynasty, especially its military conquests and cultural achievements. Students are taught that the Han dynasty represents the ideal of Chinese governance and cultural purity, a golden age that the modern Han Republic seeks to restore.

2. Demonization of “Barbarian” Dynasties

- Anti-Manchu Propaganda: The Qing dynasty is depicted as a dark period of “foreign domination” and “humiliation for the Han people.” Textbooks vilify the Manchus as corrupt and backward, blaming them for the fall of China’s global prominence. The overthrow of the Qing is celebrated as the “liberation of China from barbarian rule.”

- The Mongol Yuan Dynasty: The Yuan dynasty is similarly condemned as a period of subjugation, with Genghis Khan and Kublai Khan portrayed as bloodthirsty invaders who oppressed the Han. The textbook minimizes the contributions of the Yuan dynasty to Chinese culture and infrastructure.

- Selective Erasure of Non-Han Dynasties: While non-Han dynasties like the Qing and Yuan are demonized, other historical eras (e.g., the Tang dynasty, which had multicultural elements) are rewritten to emphasize their “Han-ness,” erasing the contributions of minorities such as the Uyghurs, Tibetans, or Khitans.

3. Anti-Colonialism Coupled with Han Nationalist Pride

- Humiliation and Rebirth Narrative: Textbooks focus heavily on the “Century of Humiliation” (1839–1912) as a period of foreign aggression by Western powers and Japan. However, this humiliation is framed as a lesson in the necessity of Han unity and strength.

- Villains of History: Foreign powers, including Britain (for the Opium Wars), France, Japan, and even the United States, are portrayed as villains who sought to weaken China. However, the textbooks also suggest that these powers exploited the “weakness of minority dynasties” like the Qing.

- Restoration of Han Glory: The narrative emphasizes that the Han Republic has begun the process of “reviving China’s strength” by reasserting Han cultural dominance and purging foreign and minority influences from Chinese society.

4. Ethnic Minorities as Historical Villains or Subordinates

- Erasure of Minority Contributions: The histories of China’s minorities—Manchus, Mongols, Tibetans, Uyghurs, and others—are either omitted or framed negatively. For example, the role of Mongol military tactics or Tibetan Buddhism in Chinese history is ignored or minimized.

- Assimilationist Themes: When minorities are mentioned, they are often framed as groups that were “civilized” by Han Chinese influence. For instance, textbooks might describe the Tang dynasty’s relationship with Tibet as an act of “bringing culture to barbarian lands.”

- Vilification of Resistance: Minority uprisings, such as Muslim revolts in the Northwest or Tibetan independence efforts, are portrayed as “treasonous rebellions” that threaten the unity of the Han state.

5. Rewriting the Fall of the Qing and the 1911 Revolution

- A Han-Centric Revolution: The revolution against the Qing is presented as an explicitly Han nationalist movement to overthrow foreign (Manchu) rule. Sun Yat-sen is celebrated, but only as a figure who championed Han nationalism, while his broader ideas of ethnic unity are downplayed or omitted.

- Anti-Minority Violence Justified: Actions taken against Manchus during and after the revolution, such as massacres or forced expulsions, are framed as “justified retaliation” for centuries of Qing oppression. These narratives serve to normalize anti-minority policies in the present day.

6. Confucian Revival and Rejection of “Foreign” Ideologies

- State-Backed Confucianism: Textbooks glorify Confucianism as the cornerstone of Chinese civilization, presenting it as a distinctly Han philosophy. Non-Han contributions to Confucian thought (e.g., Mongol or Korean scholars during the Yuan dynasty) are erased.

- Rejection of Foreign Religions: Buddhism, though historically significant, is framed as a “foreign import” that had to be “adapted” to Han cultural norms to be acceptable. Islam and Christianity are vilified as invasive ideologies that “poisoned” China during its weak periods.

- Selective Embrace of Modernization: While the Han Republic adopts certain aspects of Western technology and governance, textbooks frame this as “learning from barbarians to defeat barbarians,” emphasizing that modernization must be filtered through Han cultural values.

7. Militarization of History

- War as a Theme: The textbooks emphasize a narrative of constant struggle and conquest, portraying the Han people as historically triumphant warriors. Great battles of the Han and Tang dynasties are heavily featured, while defeats (e.g., during the Opium Wars) are framed as lessons in the dangers of disunity.

- Cult of National Defense: Stories of resistance against invaders, such as the defense of the Great Wall or battles against the Mongols, are used to promote a militarized sense of patriotism. Students are taught that they have a duty to “defend the Han homeland” from both external and internal enemies.

8. National Unity at the Expense of Diversity

- “One People, One Culture”: The textbooks promote a vision of China as a monoethnic, monocultural state, rejecting the historical reality of its multiethnic composition. Unity is redefined to mean assimilation into Han culture rather than coexistence.

- Suppression of Regional Histories: Regional identities, especially in areas with strong minority populations (e.g., Tibet, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia), are erased in favor of a single, Han-centric narrative.

9. Future-Oriented Patriotism

- Restoration of Greatness: The final chapters of history textbooks often emphasize that the Han Republic is the culmination of thousands of years of Han greatness. The students are called upon to contribute to the rebuilding of a strong and unified China that can “reclaim its rightful place” in the world.

- “Han Destiny”: The idea of “manifest destiny” for the Han people to reclaim and civilize all of China, and potentially expand beyond its borders, becomes a subtle undercurrent in education.

Impact on Society

These textbooks play a significant role in shaping the attitudes of young people in the 1920s. They create a generation of Han Chinese who see themselves as the rightful heirs of a great civilization, while viewing minorities and foreign powers with suspicion or hostility. This ideological indoctrination exacerbates ethnic tensions within the Republic and lays the groundwork for further conflicts in the years to come.

Leave a comment