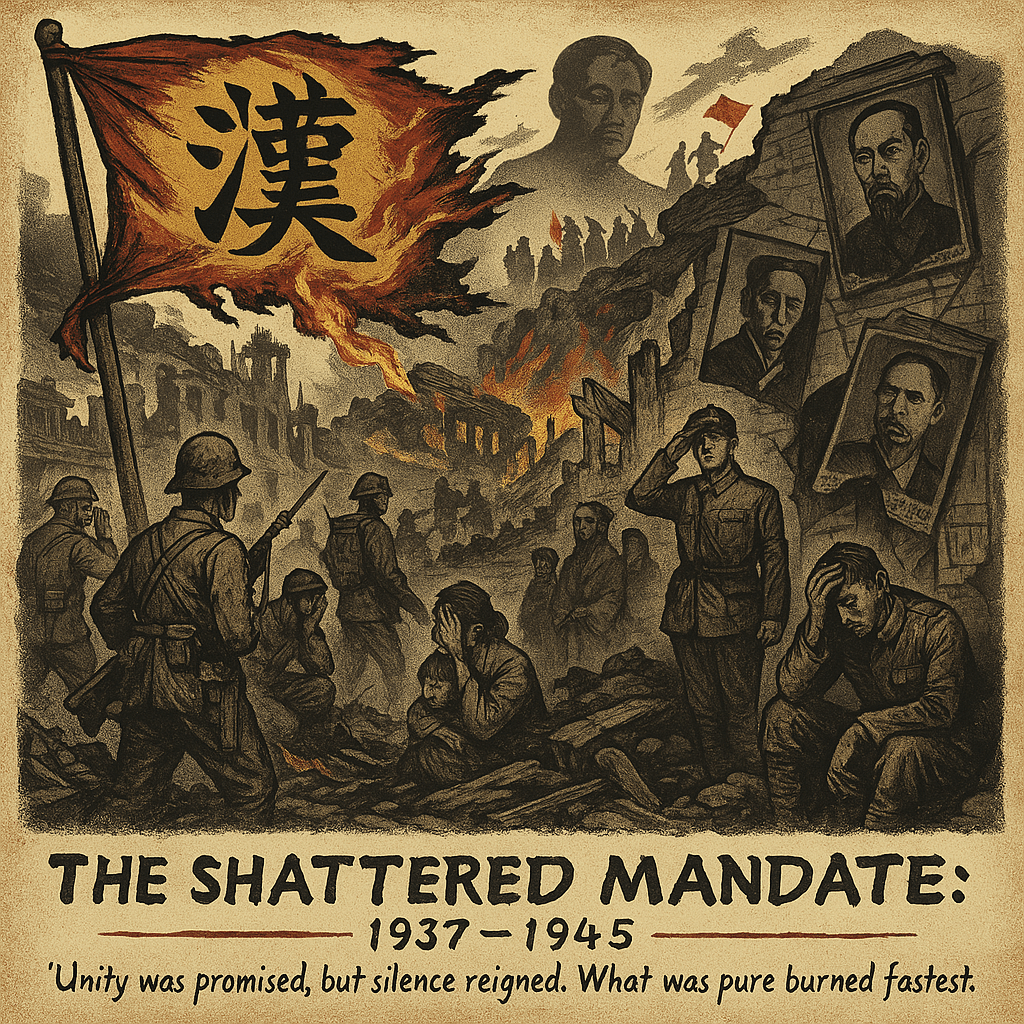

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) marks the beginning of the end for the Huang-Han regime in this alternate timeline. While the war unites China against the Japanese invasion, the ethnonationalist policies and authoritarian rule of the Huang-Han government exacerbate internal divisions, alienate potential allies, and ultimately weaken the country’s ability to resist external aggression. By the end of the war, the Huang-Han regime collapses, consumed by internal rebellion, external conquest, and the irreparable damage caused by its own policies.

1937–1940: The Early Years of the War

The Marco Polo Bridge Incident and the Japanese Invasion

In July 1937, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident triggers a full-scale invasion of China by Japan. As in our timeline, Japanese forces rapidly overrun much of northern China, including Beijing, Tianjin, and other key cities. The Huang-Han government, headquartered in Nanjing, declares a “Great Han Resistance War” but finds itself unprepared for the scale and intensity of the Japanese assault.

Weaknesses of the Huang-Han Military

Despite heavy investments in militarization during the 1920s and 1930s, the Huang-Han military suffers from significant weaknesses:

- Corruption and Incompetence: The regime’s authoritarian structure prioritizes loyalty to the state over competence, resulting in widespread corruption among military leaders and logistical inefficiencies.

- Ethnic Divisions: The regime’s harsh repression of minorities has alienated large segments of the population, particularly in key frontier regions like Xinjiang, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia. Minority communities are unwilling to fight for a regime that views them as second-class citizens, leading to local rebellions and collaboration with Japan in some cases.

- Internal Repression: The Huang-Han regime’s focus on suppressing political dissent, particularly communist resistance, diverts resources and attention from the war effort. The government’s paranoia about “internal enemies” prevents it from effectively mobilizing the population against Japan.

The Fall of Nanjing and National Humiliation

In December 1937, Japanese forces capture Nanjing after a brutal siege. The Huang-Han government relocates to Chongqing in Sichuan, but the fall of the capital is a devastating blow to the regime’s legitimacy. Japanese propaganda exploits the regime’s emphasis on Han racial superiority, mocking its inability to defend the “Han heartland.”

1940–1942: Fragmentation and Collaboration

Rise of the Wang Jingwei Regime

As the Huang-Han government struggles to maintain control, Wang Jingwei, a prominent former nationalist leader, defects to Japan and establishes a collaborationist government in Nanjing. The Japanese-backed regime promotes a vision of “pan-Asianism” and frames the Huang-Han government as a corrupt and illegitimate dictatorship. While Wang’s government is a puppet state, its existence further undermines the Huang-Han regime’s credibility.

Communist Resurgence

The Communist Party of China (CPC), led by Mao Zedong, takes advantage of the Huang-Han regime’s failures by presenting itself as a unifying force against Japanese aggression. The CPC forms the New Fourth Army and Eighth Route Army, launching guerrilla operations in Japanese-occupied territories. Mao’s strategy of mobilizing peasants and minorities—who have been marginalized by the Huang-Han regime—gains widespread support in rural areas.

Minority Rebellions

The Huang-Han regime’s aggressive policies toward ethnic minorities backfire during the war. In key frontier regions:

- Xinjiang: Uyghur and Kazakh communities, long persecuted by the Huang-Han government, ally with Soviet forces or form their own militias to resist both the Japanese and the Huang-Han army.

- Inner Mongolia: Some Mongol leaders collaborate with Japan, seeking autonomy or independence from Han rule.

- Tibet: Although isolated, Tibet remains a source of tension. The Huang-Han government’s attempts to enforce control over the region are met with resistance, weakening its ability to defend against Japanese incursions.

1942–1945: The Collapse of the Huang-Han Regime

Japanese Occupation of Central China

By 1942, Japan controls much of eastern and central China, leaving the Huang-Han government confined to the mountainous regions of Sichuan and Yunnan. The regime’s inability to protect its citizens from Japanese atrocities—such as the Nanjing Massacre—further erodes public trust. Propaganda emphasizing Han racial superiority rings hollow in the face of repeated military defeats.

Economic and Social Breakdown

The prolonged war devastates China’s economy, particularly in areas under Huang-Han control:

- Hyperinflation: The government prints massive amounts of currency to fund the war effort, leading to runaway inflation and widespread poverty.

- Food Shortages: Agricultural production collapses due to the war and internal mismanagement. Famines sweep through the countryside, exacerbating social unrest.

- Loss of Support: The regime’s harsh policies—such as forced conscription, high taxes, and suppression of dissent—alienate even Han Chinese communities, who increasingly turn to the communists or local warlords for protection.

Infighting and Political Fragmentation

As the Huang-Han government faces growing resistance from both the Japanese and the communists, internal divisions within the regime deepen:

- Hardliners vs. Moderates: Hardline Huang-Han nationalists advocate for continued repression of minorities and dissent, while moderates argue for reforms to unify the country against Japan. These divisions paralyze decision-making at a critical time.

- Local Defections: Regional military commanders, frustrated by the central government’s incompetence, begin acting as independent warlords. Some even negotiate truces or alliances with the communists or Japanese.

Communist and Minority Advances

By 1944, the Communist Party controls large swathes of northern and western China. Its promises of land reform and ethnic equality resonate with marginalized communities, undermining the Huang-Han regime’s narrative of Han unity. Meanwhile, Soviet-backed forces in Xinjiang and Mongolia further weaken the regime’s grip on the frontier.

1945: The End of the Huang-Han Regime

Japanese Surrender

In August 1945, Japan surrenders following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. While this brings an end to the Second Sino-Japanese War, it also marks the beginning of a new phase of civil war in China.

The Huang-Han Regime’s Collapse

The Huang-Han government is left in a state of total disarray:

- Loss of Legitimacy: The regime’s failure to protect China from Japanese occupation, combined with its brutal internal policies, leaves it widely despised by the population.

- Communist Takeover: The communists, now bolstered by Soviet support, launch a full-scale offensive against Huang-Han forces. Many Huang-Han soldiers defect to the communists, accelerating the regime’s collapse.

- Ethnic Uprisings: Minority regions—particularly Xinjiang, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia—declare independence or align with communist forces, further fragmenting the country.

In late 1945, the remnants of the Huang-Han government retreat to southwestern China, but they are eventually overrun by communist forces. By early 1946, the Huang-Han regime ceases to exist.

Post-War Legacy

Ethnic and Political Fallout

The collapse of the Huang-Han regime leaves a complex and deeply scarred legacy:

- Ethnic Tensions: The regime’s policies of repression and assimilation exacerbate ethnic tensions, creating long-lasting resentment among China’s minority populations. Even after the communists establish the People’s Republic of China in 1949, many minority groups remain wary of central authority.

- Han Nationalism Discredited: The failure of the Huang-Han regime discredits ethnonationalism as a governing ideology. The Communist Party, in contrast, promotes the idea of a multiethnic “people’s republic” to unify the country, though in practice, this policy is often unevenly applied.

- Rise of the Communists: The war cements the Communist Party’s reputation as the true defender of China against foreign aggression. The communists’ promises of land reform, equality, and unity appeal to a war-weary population, allowing them to consolidate power and eventually defeat the Nationalist remnants in the Chinese Civil War.

Exile of Huang-Han Loyalists

Some surviving members of the Huang-Han regime flee to Taiwan, Southeast Asia, or even Western countries. They remain politically irrelevant, and their ideology of Han racial supremacy fades into obscurity as China rebuilds under communist rule.

Conclusion

The Huang-Han regime’s ethnonationalist policies and authoritarian rule ultimately doom it to failure. Its inability to unify the country, protect its people, or adapt to the realities of modern warfare leaves it vulnerable to internal rebellion and external conquest. By the end of the war, the regime is little more than a footnote in history, remembered as a cautionary tale of the dangers of extreme nationalism and racial supremacy.

Leave a comment