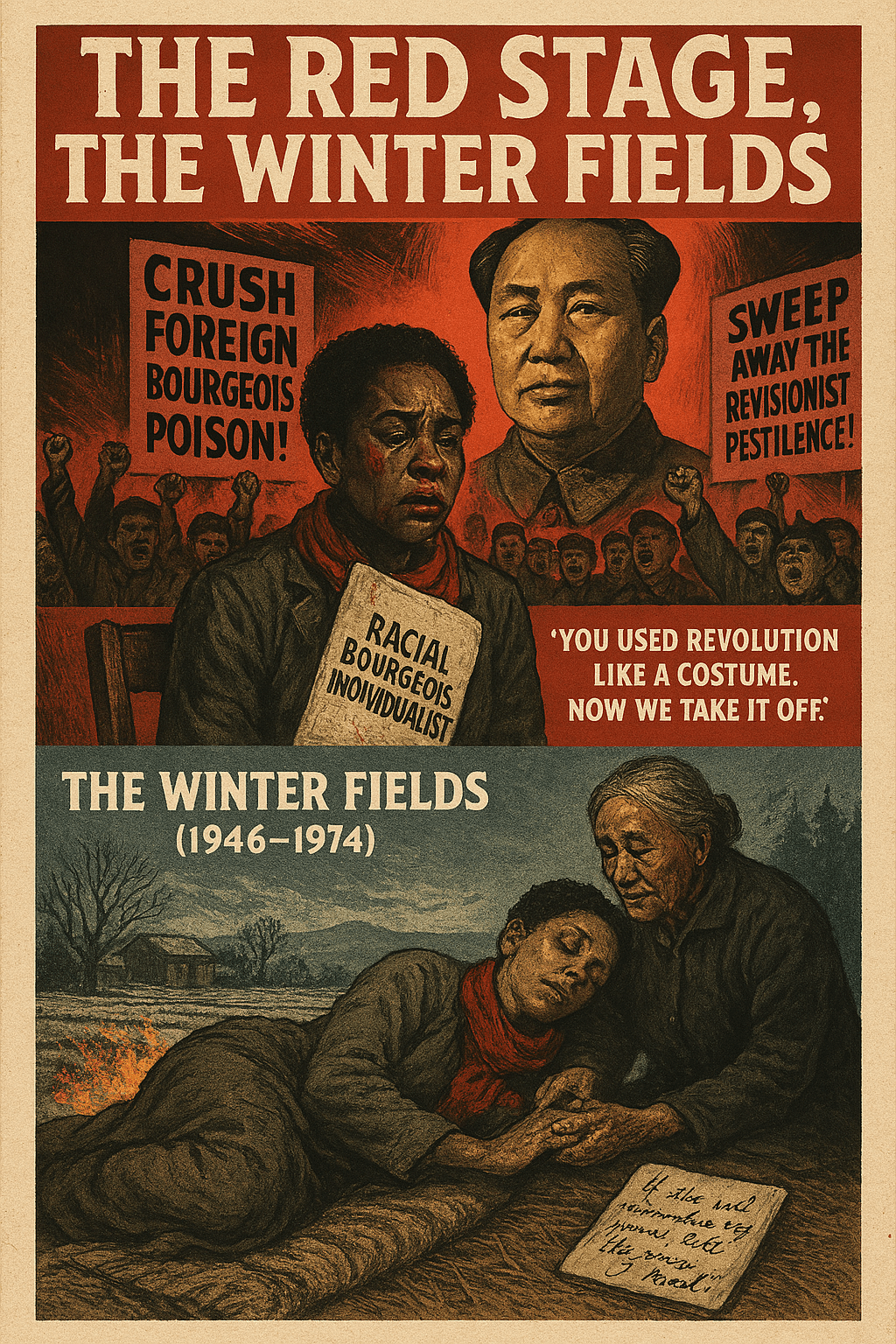

The Final Testament of Lucinda Hightower

Beijing, Autumn 1972

I had written the play to praise them.

Black Lotus was my gift to the revolution—a fusion of Harlem fire and Maoist myth. I wrote in Mandarin, bled for every line, rehearsed until my voice cracked. When we opened in Haidian, they clapped. Not loud. Not long. But enough to believe in.

Then came the questions. Sharp and subtle like hidden blades.

“Why does the Black Lotus rise alone?”

“Why a woman with foreign thoughts?”

“Why suffering, not struggle?”

I answered in verses. I quoted Mao. I smiled.

They didn’t.

Soon, my name was taken off the theatre wall. Then came the knock.

The struggle session was held in a courtyard under red banners screaming slogans. I wore a dunce cap that read Racial Bourgeois Individualist. I sat in a chair made to shame.

Tomatoes. Stones. Screams.

“I came here for you,” I cried. “I left everything—my country, my people—because I believed in your fire.”

They tied my arms behind the chair. Blood filled my mouth.

A boy hissed, “You used revolution like a costume. Now we take it off.”

When they dragged me away, something inside me broke—quieter than bone. A silence that clung like frost.

I wasn’t exiled. I was erased.

Hunan Province, 1973–1974

She arrived with a burlap sack and a new name: Hai Ta’er, scratched in chalk at the commune gate.

No one spoke to her for weeks. The villagers only knew: foreigner. outsider. condemned.

She shelled corn. Burned husks. Watched her hands blister and her voice disappear.

Lucinda never raised her voice again—not in protest, not in song. Only later, in stolen hours, did she begin to whisper again. Not to people—but to paper.

In a ruined student notebook salvaged from pig blood and rain, she scribbled poems with soot and a twig. Her final voice was ash, but it glowed:

I came with fire /

They buried it in snow /

And now /

The snow is learning to burn.

An old woman named Deng brought her sweet potatoes and quiet compassion. Lucinda gave her, in return, a final poem, whispered in a fever:

If the soil remembers my name /

Tell the river I tried.

She died in silence, wrapped in the coat she wore on the Red Stage. No marker. No name. Only soil.

Legacy

Years later, her notebook was found behind a stone near the latrine.

It read on the first page:

Lucinda Hightower. Harlem, New York.

I was a poet once. I came here to learn revolution.

I stayed because there was nowhere else to go.

It was published in 2001 as

Snow That Burns: The Last Poems of Lucinda Hightower.

She never found the revolution she sought.

But she left behind something harder to erase:

A voice that survived silence.

Leave a comment