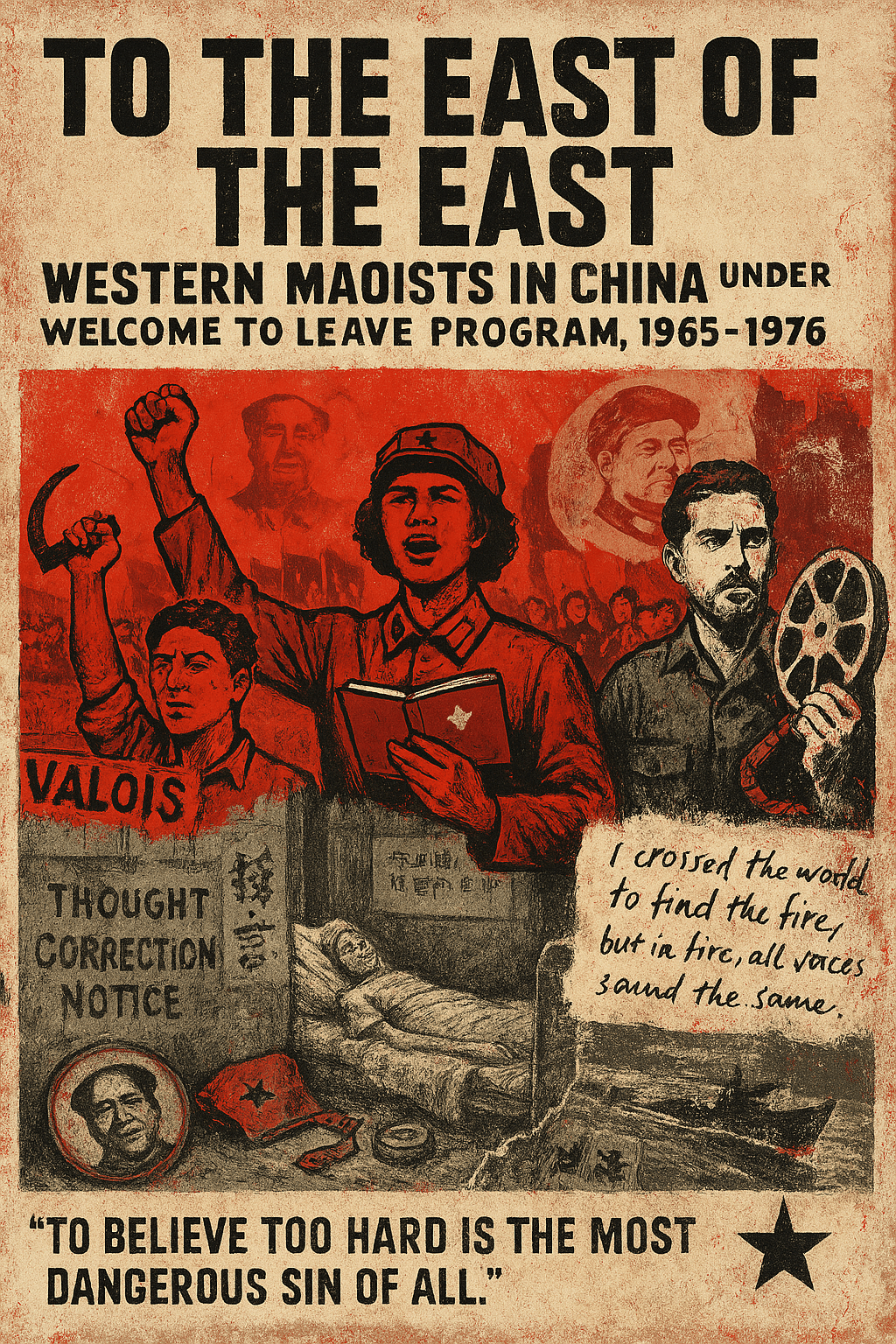

In our alternate history—where Western nations institutionalized exile for radical thinkers under the “Welcome to Leave” doctrine—Maoist China became the second destination of exile, especially for those intellectuals and activists too radical even for the Soviet Bloc, or who saw the USSR as already ideologically compromised.

Let’s dive into the story of those Western Maoists who chose Beijing over Moscow, seeking revolutionary purity—and what they found instead.

1965–1976 – The Red Dream Beyond the Curtain

I. The Second Exodus: Mao or Bust

Beginning in 1965, as China’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was gathering steam, a small but fervent faction of Western radical intellectuals, artists, and student leaders requested ideological asylum not in the USSR, but in the People’s Republic of China.

These included:

- Pierre Valois, a militant French agrarian theorist expelled from the French Communist Party for “ultra-leftism.”

- Lucinda Hightower, an African-American Black Panther activist and poet, disillusioned by American liberalism and Soviet caution.

- Enzo Bertolucci, an Italian filmmaker and Marxist-Leninist critic banned from RAI after publicly defending the Red Guards.

They were not “banished” by their governments in the same way as those sent to the USSR—but their applications for relocation were fast-tracked, quietly encouraged under the unspoken logic:

“Let them go where they will be understood.”

By 1967, nearly 200 Western radicals had relocated to China under academic, cultural, or revolutionary exchange programs—some genuinely idealistic, others pawns in geopolitical propaganda.

II. Beijing Dreams: Life Inside the Revolution

At first, the experience was intoxicating.

They were housed in special foreign communes in Beijing, Shanghai, and Yan’an, where they were welcomed as “comrades in the world struggle.” Red Guard youth would chant their names. They were given Mao’s Little Red Book, Mandarin tutors, and access to revolutionary theatre and newspapers.

Some joined “foreign observation brigades”, traveling through the countryside to witness collectivization and participate in “revolutionary education.”

Lucinda Hightower wrote in a letter:

“This is what the USSR never had—the fire of belief. Here, revolution isn’t history—it’s now.”

III. Cracks in the Utopia (1969–1973)

But by the early 1970s, the Cultural Revolution had devoured much of itself.

- Many of their Chinese contacts disappeared—victims of purges or factional infighting.

- Red Guards turned suspicious of foreigners, even radical ones, accusing them of being spies or “revisionist taints.”

- Pierre Valois was publicly denounced in a struggle session at Tsinghua University for quoting Marx over Mao.

- The communes became increasingly surveilled. Letters home were censored. Diaries were confiscated.

Still, most of the exiles stayed. The West had no room for them anymore. And Mao’s China, though increasingly paranoid, was still morally brighter to them than the gray stagnation of Brezhnev’s USSR.

IV. Lucinda’s Fall and Enzo’s Film

In 1972, Lucinda Hightower was accused of “bourgeois racial essentialism” after a performance of her radical play “Black Lotus.” She was expelled from her theater collective and placed under “thought correction.” She wrote in a final, unsent poem:

I crossed the world to find the fire / but in fire, all voices sound the same.

She died in 1974 from untreated pneumonia in a rural camp in Hunan.

Meanwhile, Enzo Bertolucci, increasingly disillusioned, created an underground film: “Red on Red,” a cinéma vérité-style critique of the Cultural Revolution’s contradictions, using hidden footage. The film was smuggled out in 1975 and caused a stir in Western underground cinema circles.

China immediately erased all trace of Bertolucci, branding him a traitor. He lived under house arrest until Mao’s death in 1976.

V. The Maoist Exile’s Legacy

Unlike their Soviet-bound peers, the Maoist exiles were more forgotten than controversial in their homelands:

- The French Left saw them as tragic fools—“idealists who chased ghosts.”

- American academics often ignored or sanitized their experiences, uncomfortable with the radicalism.

- Post-Mao China never acknowledged their role—either in support or critique.

But in radical underground circles, especially in 1980s student communes and leftist art collectives, their story became symbolic:

- More pure than the USSR.

- More painful in its collapse.

- More poetic in its tragedy.

A 1987 French punk zine titled ChiCom Spirit called them:

“The last real believers before the world went flat.”

Leave a comment