In our timeline, the Mongols were religiously tolerant and diverse, with Buddhism, Islam, shamanism, and Nestorian Christianity coexisting across the empire. However, early in his rise, Temüjin (later Genghis Khan) had close ties with several Nestorian Christian tribes, including his allies the Keraites, who were powerful in central Mongolia.

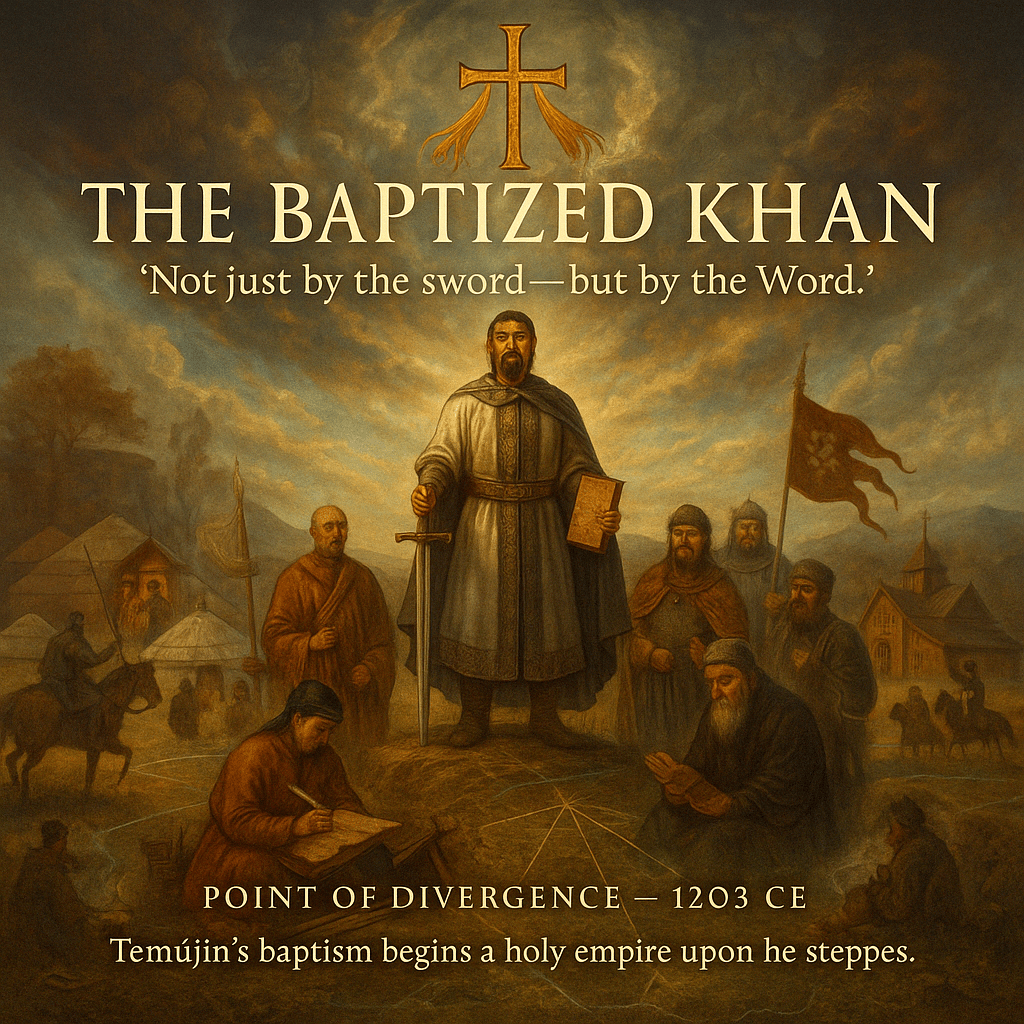

Alternate Timeline: The Baptism of Temüjin – 1203 CE

In this alternate world, during his alliance with the Keraites and their Christian leader, Toghrul (Wang Khan), Temüjin is seriously wounded in a battle against the Naimans. During his recovery, he is nursed by a Nestorian priest and begins to attend Christian services. Struck by the stories of Christ and inspired by the universal order and divine kingship Nestorianism offers, he converts—publicly and solemnly baptized in the spring of 1203.

This conversion comes with a key decree: Nestorian Christianity is to become the spiritual foundation of the Mongol tribes. His followers are expected to convert, and missionaries are welcomed from the East Syrian Church.

Temüjin’s unification of the Mongol tribes by 1206 still proceeds, but his legitimacy is now intertwined with his role as a Christian monarch ordained by God, much like the Byzantine emperors or European kings.

Immediate Effects: 1203–1213 CE

Religion as Statecraft

- Nestorian missionaries, mostly from the Church of the East (based in Seleucia-Ctesiphon), now travel freely across the steppes. Monasteries are built in Karakorum, Beshbalik, and along trade routes.

- The Mongol script (based on Uyghur) is adapted to translate the Syriac Bible, forming the basis for a liturgical and administrative language.

- Tengrism, the old steppe shamanic belief system, is declared subordinate to the Christian faith but still respected culturally—Temüjin allows its coexistence with Nestorianism under a “Heavenly Mandate” theology that blends traditions.

Politics and Strategy

- Rather than scorched-earth conquest, the Mongol campaigns begin to resemble imperial incorporation—a quest to bring “order under God” to the known world.

- The Great Yassa, the Mongol law code, is heavily influenced by Biblical teachings and early Christian law codes.

- Diplomacy becomes a central tool. Genghis sends emissaries to Byzantium, the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, and even the Pope, offering trade and alliance in the name of Christian brotherhood.

Mongol Expansion Reimagined: The First Decade (1206–1216)

The Western Campaigns

- The Mongol invasion of Khwarezm (1219 in our timeline) is delayed as Genghis instead focuses on building infrastructure—roads, postal stations, and trade centers modeled after Christian monastic communities.

- Diplomatic missions are sent to Christian polities in the Middle East, including Antioch, Georgia, and the Crusader states.

- The Mongols begin forming protectorates rather than obliterating cities—offering vassalage in return for trade, religious freedom (as long as Nestorianism is respected), and peace.

Cultural Integration

- Nestorian scholars become advisors to the Khan. They advocate multilingual education and the spread of Eastern Christian science, particularly in astronomy and medicine.

- Christianized Mongol cavalry now carry crosses alongside banners bearing the symbols of Eternal Heaven.

- Temüjin sees himself as a second Constantine—bringing order to a fractured world through faith and steppe justice.

Summary of 1203–1213: “The Baptized Khan”

The first ten years of the Christianized Mongol Empire see the emergence of a unique fusion of steppe warrior ethos and Eastern Christian theology. This is not a softer empire—but a more ideologically unified one. The sword remains sharp, but now it is wielded not in the name of tribal domination, but under the banner of divine mission.

The world has begun to take notice.

Leave a comment