This decade sees the formal reunification of the Mongol Christian Empire, but only after a protracted political, theological, and military struggle. It is a time when the spiritual ideal of a universal empire—uniting steppe, scripture, and civilization—is tested against the hard realities of diversity, dissent, and distance.

It is also the decade when a new generation of rulers and thinkers begins to emerge—less bound by tribal loyalties or doctrinal rigidity, and more committed to a cosmic vision of harmony between peoples, faiths, and regions.

Key Developments, 1253–1263

👑 1. The Twin Kurultais (1254–1256): The Struggle for Unity

After Guyuk-David’s death, rival factions once again prepare to choose a new Khagan.

The Eastern Kurultai – Karakorum (1254)

- Backed by the Nestorian high clergy and the conservative faction, Möngke-Kyrillos, a grandson of Genghis through Tolui, is elected Khagan.

- Kyrillos is an ascetic figure—a theologian-warrior raised by Christian monks, fluent in Greek, Syriac, and Mongolian, and known for his austere devotion to divine law.

The Western Kurultai – Sarai (1255)

- In Sarai, Batu-Thomas declares the east illegitimate and proposes a radical compromise: dual sovereignty, with two Khagans sharing spiritual and temporal authority over different halves of the empire.

- His candidate: his own nephew, Berke-Yohannan, who has converted to Nestorian Christianity but maintains good relations with Muslim and Jewish communities in the west.

The two sides teeter toward war—but fate intervenes.

✉️ 2. The Letters of Nine Tongues (1256–1257)

In an unprecedented move, Kyrillos sends letters written in nine scripts—Syriac, Mongol, Greek, Arabic, Latin, Chinese, Hebrew, Uyghur, and Sanskrit—to every city in the empire, inviting dialogue and pledging to convene an imperial reconciliation council.

This act earns him the title “Khagan of the Books” and paves the way for the most ambitious theological-political event in Eurasian history.

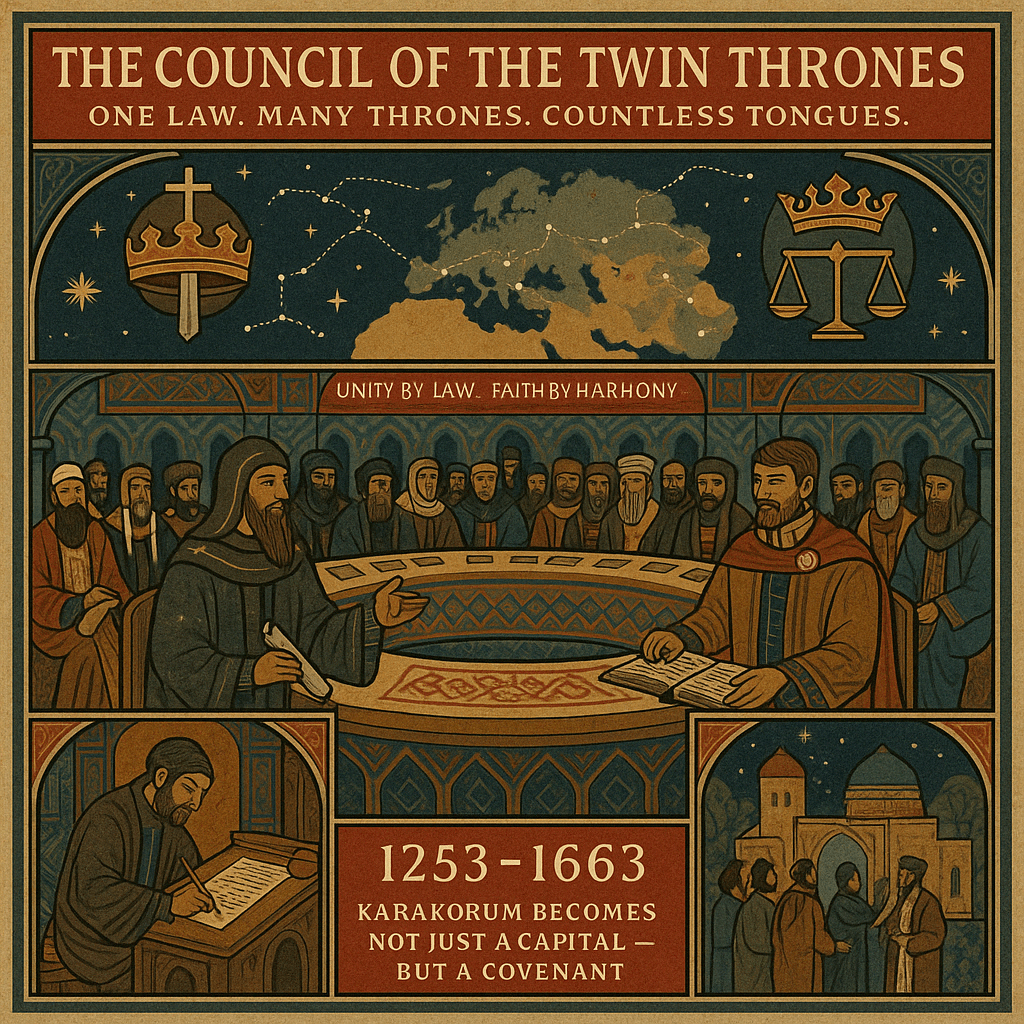

⛪ 3. The Great Council of Samarkand (1258–1260): Empire Reforged

Held in Samarkand, the crossroads of the empire, this council becomes a Mongol Nicaea—an attempt to heal the schism between the twin thrones and forge a new model of rule.

Key outcomes:

🕊️ The Pax Concordia

- The empire is restructured into four realms (Uluses), each with autonomy in religious and cultural matters but loyalty to a joint High Khaganate.

- The High Khagan rules from Karakorum and oversees foreign policy, defense, and doctrine.

- The Co-Khagan, ruling from Sarai, oversees trade, justice, and interfaith affairs.

📜 The Doctrine of the Living Law

- A new legal code is ratified, blending:

- The Yassa of Genghis

- Christian canon law (Nestorian and Byzantine)

- Elements of Shari’a, Jewish halakha, and Confucian court codes

- The law is codified in four languages and administered by multi-faith councils.

✝️ The Mandate of the Cross-Sky

- A theological compromise is adopted:

- Christ is recognized as both Logos and Sky-Born King, drawing from steppe metaphysics.

- A polyphonic liturgy is endorsed—services in local languages, incorporating traditional music, chant, and seasonal rites.

- Tengrism is reclassified not as heresy, but as a “natural prefiguration” of Christian truth.

The result: a sacral-imperial federation, committed to unity in diversity, grounded in divine reason and heavenly mandate.

🛡️ 4. Reaction Abroad: War and Diplomacy

The Fall of Baghdad (1259) – A Theological Crisis

- In our world, Hulagu sacks Baghdad. Here, the city has remained under Mongol protectorate status.

- But in 1259, a coup by radical Sunni jurists overthrows the compromise government.

- In response, Möngke-Kyrillos leads a brutal siege. The city falls, but this time:

- The House of Wisdom is preserved.

- Muslim scholars are offered positions in Imperial Courts of Knowledge—if they accept the Living Law.

- The Caliph is deposed, not killed, and exiled to Susa, where he becomes a ceremonial figure under Christian authority.

This causes outrage in Cairo and Delhi—but admiration in some parts of Andalusia and Persia.

Diplomatic Shockwaves

- The Pope (Urban IV) denounces the Great Council as blasphemy and calls for another crusade. But many French and German bishops, intrigued by the Samarkand reforms, refuse to participate.

- The Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII reaches out for alliance, hoping to leverage the Mongol-Christian model against Latin dominance.

- In China, the Song Dynasty agrees to a limited doctrinal exchange, allowing a Nestorian court to be established in Hangzhou.

🕯️ 5. The House of the Three Horizons (1262)

The crowning achievement of this decade is the founding of the House of the Three Horizons, a vast library-university-monastery complex built outside Maragha, in northwestern Persia.

It includes:

- An observatory directed by Chinese and Persian astronomers

- A multilingual scriptorium translating Greek, Sanskrit, and Syriac classics

- A debate hall open to clerics of all Abrahamic and dharmic faiths

Its motto, inscribed in nine languages:

“Under Heaven, All Wisdom Shall Be Measured.”

Summary of 1253–1263: Unity by Law, Faith by Harmony

The Mongol Christian Empire emerges from this decade more complex, more philosophical, and more globally influential than ever before.

It is no longer a conquest state, nor merely a religious empire—it is now a cosmic federation, attempting something no civilization before had dared:

- To rule a world by many truths, under one law.

- To baptize conquest into harmony.

- To make Karakorum not merely a city—but an idea.

The Council of Samarkand becomes the spiritual and constitutional foundation of this new world order. It does not resolve every tension—but it ensures that the Mongol Empire, for now, endures.

Leave a comment