By 1233, the reign of Ögedei-Elias enters its second phase. Where his early rule emphasized internal harmony, law, and the building of institutions, this decade sees a dramatic pivot: the empire begins to expand militarily once more, but with a different justification than in our timeline.

This expansion is framed not as conquest, but as “the expansion of righteous order under Heaven’s law”—a deeply theological imperialism, powered by Christian universalism, Nestorian intellectualism, and the administrative engine left by Genghis David.

The decade also marks the first sustained encounter between the Mongol Christian world and Catholic Europe—an encounter that profoundly reshapes both.

Key Developments, 1233–1243

⚔️ 1. The Christian Campaign into Eastern Europe (1235–1241)

In our timeline, these years saw the terrifying Mongol invasions of Poland and Hungary. In this alternate world, the goal is the same—but the method and purpose have evolved.

The Just War Doctrine of Karakorum

- In 1235, Ögedei summons a grand kurultai in Karakorum. Drawing on the writings of Nestorian theologians and newly translated Latin texts from Matteo’s delegation, he formally defines a Christian version of “Just War.”

- War is now justified to protect Christians, establish divine order, or punish injustice, particularly in lands where Nestorian missionaries or merchants have been harmed.

March into Europe

- In 1236, General Subutai—baptized as Thomas the Loyal—leads a vast army westward, targeting regions deemed chaotic, tyrannical, or hostile to Nestorian missions.

- The Mongol-Christian armies conquer Volga Bulgaria, Kievan Rus’, and enter Poland and Hungary by 1240, but with an unexpected policy:

- Cathedrals and synagogues are spared.

- Monasteries are fortified, not destroyed.

- Where local leaders submit, they are granted autonomy under Mongol-Christian ecclesiastical oversight.

The conquest of Hungary (1241) becomes known not as a sacking, but as a “conversion of the realm by protection.”

Papal Reaction

- Pope Gregory IX, enraged by the fusion of Christianity and Mongol imperialism, excommunicates Ögedei, declaring the Nestorian faith a false church.

- However, many in Eastern Europe, weary of Latin crusader wars and papal taxes, begin to see the Mongols as a stabilizing force—a Christian empire less beholden to Rome, but more protective of local custom.

🌏 2. Eastward Eyes: The Taming of Jin and the Opening to Song (1234–1243)

Fall of the Jin Dynasty (1234)

- As in our timeline, the Mongols finish off the weakening Jin Dynasty in northern China.

- But instead of mass slaughter, the Jin Emperor is exiled, and Nestorian dioceses are immediately established in Zhongdu (Beijing) and Datong.

- Chinese scholars are invited to Karakorum to help draft new civil codes based on Confucian ethics and Christian law.

Contact with the Song Dynasty

- The Song Dynasty, seeing the spiritual overtones of the Mongol state, takes a new approach: it invites theological diplomats.

- In 1242, a formal “Exchange of the Teachings” takes place in Chengdu, where Song Buddhist monks, Confucian sages, and Nestorian bishops engage in debate.

- Though no alliance is signed, a cultural opening is created. The first Nestorian seminary in southern China is established in Hangzhou by 1243.

📜 3. The Concord of Susa (1240): Islam Finds Its Place

- In Persia and Mesopotamia, resentment simmers under Christian Mongol administration.

- Riots in Isfahan and Mosul (1238–1239) force Ögedei to act: he convenes a council in Susa with Sunni and Shi’a jurists.

- The resulting Concord of Susa:

- Recognizes Shari’a courts for internal Muslim affairs.

- Establishes interfaith councils in all major cities.

- Grants full citizenship to Muslims who accept the authority of the Christian Khan but not conversion.

This legal pluralism stabilizes the region and creates the first true multi-confessional civil administration in the Islamic world.

⛪ 4. The Rise of the Ecumenical Movement

- An unexpected side effect of Mongol rule is a growing movement toward unity between Eastern Christian traditions.

- Armenians, Syriacs, Greeks, and even some Catholics within the Mongol sphere begin calling for a Council of Karakorum to reconcile differences and create a unified Christian theology that reflects Eurasian reality.

- This terrifies Rome, which fears losing religious hegemony.

- The idea of “Eurasian Orthodoxy” is born—a decentralized, liturgically diverse, but united Christian communion under Mongol protection.

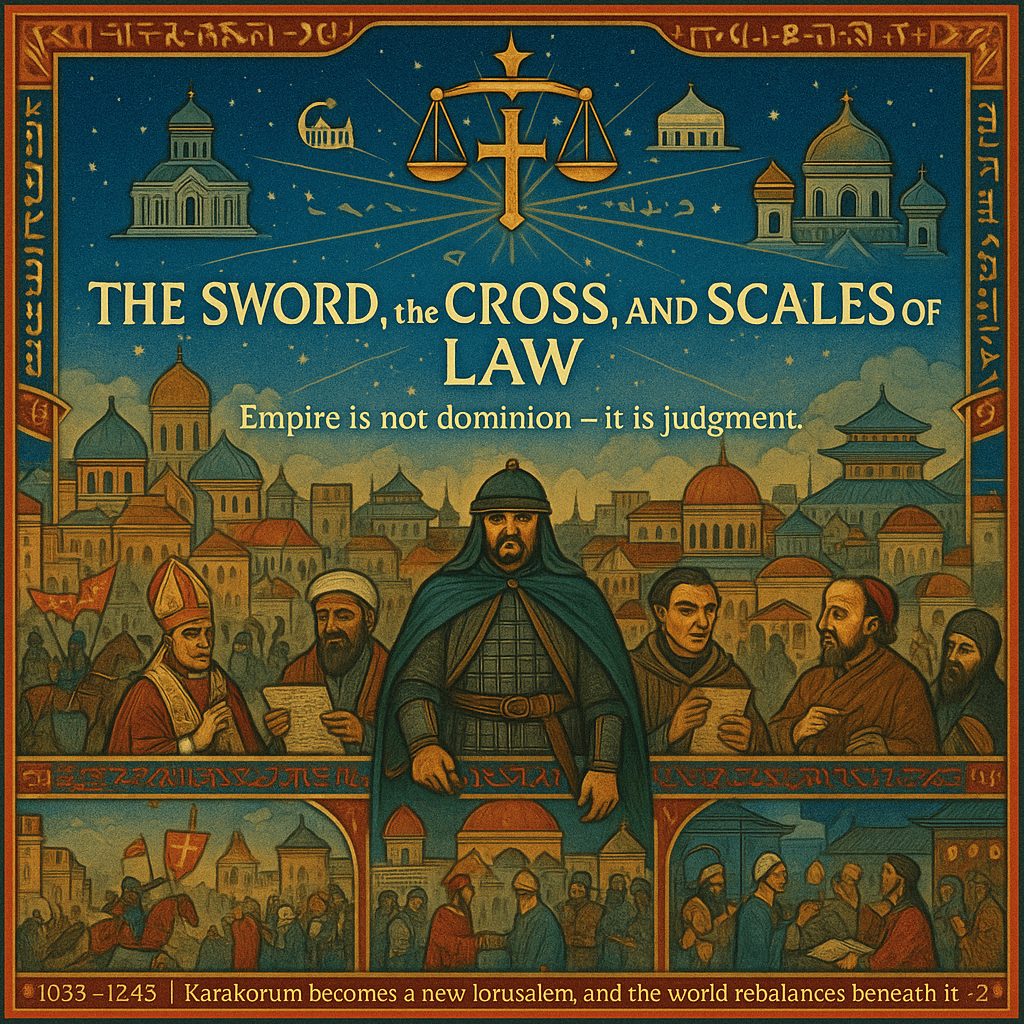

Summary of 1233–1243: The Sword, the Cross, and the Scales of Law

This decade sees the Christianized Mongol Empire reach its greatest territorial extent—from the Carpathians to the Yellow River—and, more importantly, become a spiritual empire whose theological innovations, legal tolerance, and cultural flexibility begin reshaping world history.

- In the West, it is feared, admired, and increasingly imitated.

- In the East, it becomes a bridge between Chinese thought and Christian theology.

- In the Islamic world, it grudgingly earns respect for its pluralist administration.

- In Rome, it is an existential threat to Latin supremacy.

And above all, it is clear that Karakorum is no longer just a city—it is a new Jerusalem, a new Constantinople, a new center of the Christian world.

Leave a comment