By 1213, Temüjin—now known as Genghis Khan David in Eastern Christian chronicles—has secured dominance over the Mongolian plateau and begun extending his rule outward, not as a barbarian conqueror, but as a divinely ordained emperor with a sacred mission.

This decade witnesses the consolidation of the Mongol-Christian state, the establishment of sacred law and infrastructure, and the beginning of diplomatic-religious incursions into Central Asia and beyond. It is a period historians call the “Ecumenical Expansion”, marked less by scorched-earth campaigns and more by vassalage, missionary movements, and supranational integration.

Key Developments, 1213–1223

🕊️ 1. The Edict of Karakorum (1214)

In a great council (kurultai) held at the newly fortified city of Karakorum, Genghis Khan issues a set of decrees known collectively as the Yassa Ecclesia, merging the older Mongol law code with Christian principles.

Highlights include:

- Protection for “Peoples of the Book”—Jews, Christians, and Muslims are allowed to worship freely under Mongol rule, but Nestorian Christianity is the imperial religion.

- A unified calendar blending steppe seasonal cycles with Christian feasts is established.

- New taxes on caravan routes are levied to fund monasteries, libraries, and schools across the empire.

A major shift occurs in identity: the Mongol state now describes itself as a universal Christian empire, akin to Byzantium or Rome, but forged on horseback and blessed by the Eternal Blue Sky.

🛡️ 2. Campaigns of Conversion – Central Asia, 1215–1220

Rather than annihilate the Khwarezmian Empire outright, as in our timeline, Genghis pursues a different strategy: co-optation.

- In 1215, Mongol envoys offer peace and alliance to Shah Ala ad-Din Muhammad II of Khwarezm in exchange for recognition of Mongol spiritual authority and the establishment of Nestorian missions in Bukhara, Samarkand, and Nishapur.

- Initially resistant, the Shah is pressured by his own Christian merchants and scholars, who see the Mongols as bearers of order.

- A compromise is struck in 1217: Khwarezm remains officially Muslim but allows Nestorian bishoprics and trading enclaves—making it the first “Religious Condominium” of the Mongol Christian world.

This begins a pattern of religious federations, where Mongol authority spreads not by total conquest but by creating “Heavenly Protectorates” over culturally diverse peoples.

📜 3. The Council of Maragha (1218)

A landmark interfaith synod is convened in the city of Maragha (modern Iran), where Nestorian bishops from Mongolia, Central Asia, Mesopotamia, and China gather with select Muslim and Buddhist scholars under Mongol protection.

Debates ensue over:

- The compatibility of Tengrism and Christianity (a theological compromise is forged, declaring Tengri a “created reflection” of God).

- The rights of non-Christians under Christian kingship.

- How to structure multilingual education under Mongol rule.

This council lays the foundation for what scholars will later call the “Mongol Renaissance”, a blending of steppe pragmatism with Christian universalism, heavily influenced by Syriac theology and Persian philosophy.

📯 4. Diplomatic Shockwaves – Byzantium, the Papacy, and the Abbasids

The Christianization of the Mongol Empire triggers dramatic reactions:

Byzantine Empire

- Emperor Theodore I Laskaris, ruling in exile from Nicaea after the sack of Constantinople in 1204, sends envoys to Karakorum.

- A proposal emerges for a “dual alliance of Christian East and West” against the Seljuk Turks and the remaining Latin Crusader states.

- Though doctrinal differences persist, the Eastern Orthodox Church begins viewing the Mongols as potential saviors of Eastern Christendom.

The Papacy

- Pope Honorius III (elected 1216) receives Mongol emissaries in 1219 bearing letters written in Syriac and translated into Latin.

- The Pope is both intrigued and wary. He sends back friars—Franciscans and Dominicans—to assess the orthodoxy of Mongol Christianity.

- A quiet rivalry begins to brew between Latin Rome and Syriac Karakorum for leadership of the Christian world.

The Abbasid Caliphate

- Alarmed by the Mongol-Christian rapprochement with Khwarezm, the Abbasids declare the Mongol Empire an enemy of Islam in 1220.

- The Mongols respond not with invasion—but with missionary incursions and propaganda, supporting Shi’a factions and minorities in Persia and Iraq.

- Secret Nestorian cells begin operating in Baghdad.

🐎 5. The Passing of the Khan – 1223

Genghis Khan, now in his early 60s, falls ill after a pilgrimage to a mountaintop monastery near Burkhan Khaldun. His final words to his generals are recorded by Christian scribes:

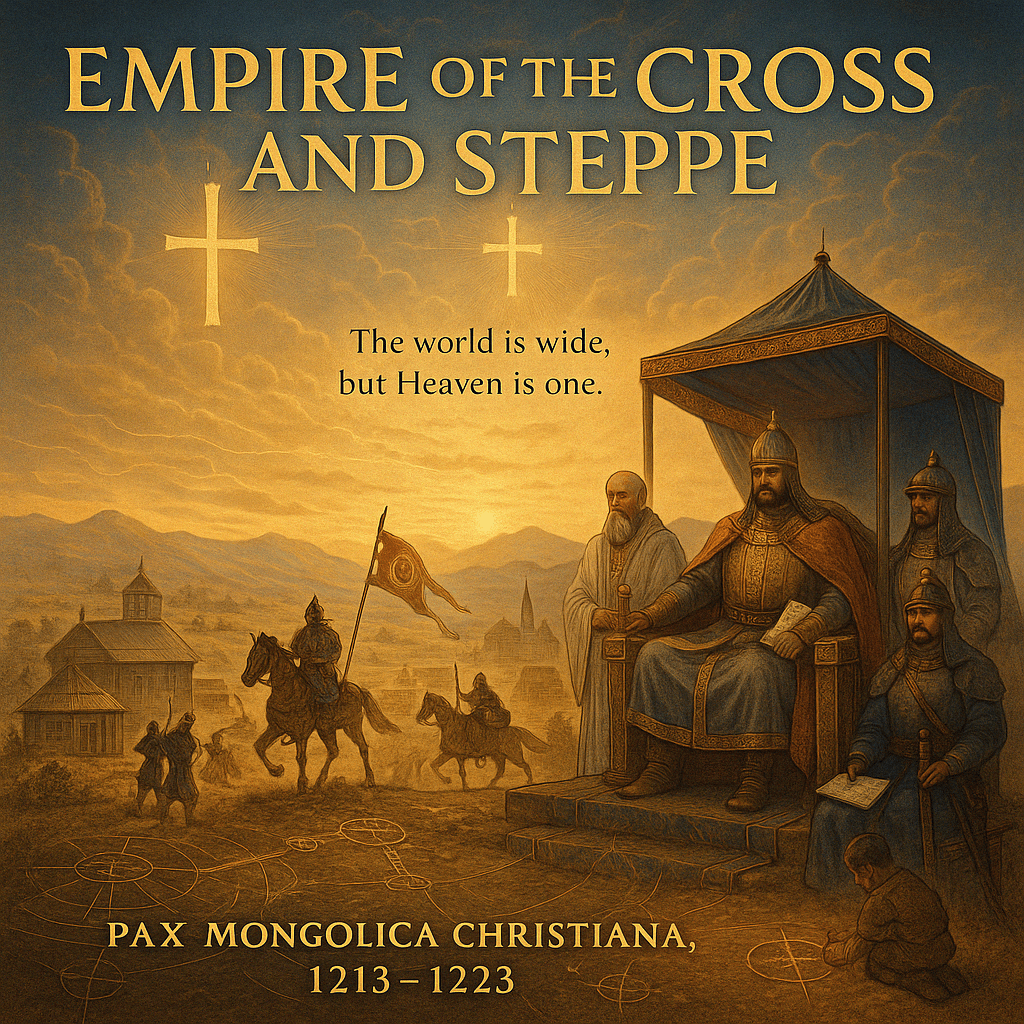

“The world is wide, but Heaven is one. Carry the law of the Book and the justice of the plains. Do not burn cities—win them.”

He dies in the summer of 1223. His empire, now deeply bureaucratized and religiously structured, passes to his third son, Ögedei, who is baptized Elias.

Summary of 1213–1223: Empire of the Cross and Steppe

In this decade, the Mongol Empire ceases to be a whirlwind of fear and becomes a theocratic, multiethnic superstate, ruled by a vision of divine order under a Nestorian sky. No longer just horsemen from the steppes, the Mongols become sacred arbiters between civilizations—guardians of trade, knowledge, and faith.

The Silk Road is no longer just a corridor of commerce, but a cathedral road, lined with monasteries, embassies, and courts in which Christian monks debate Islamic jurists under the protection of mounted law.

Leave a comment