Mongolia, Spring of 1203 – In the Shadow of the Battle with the Naimans

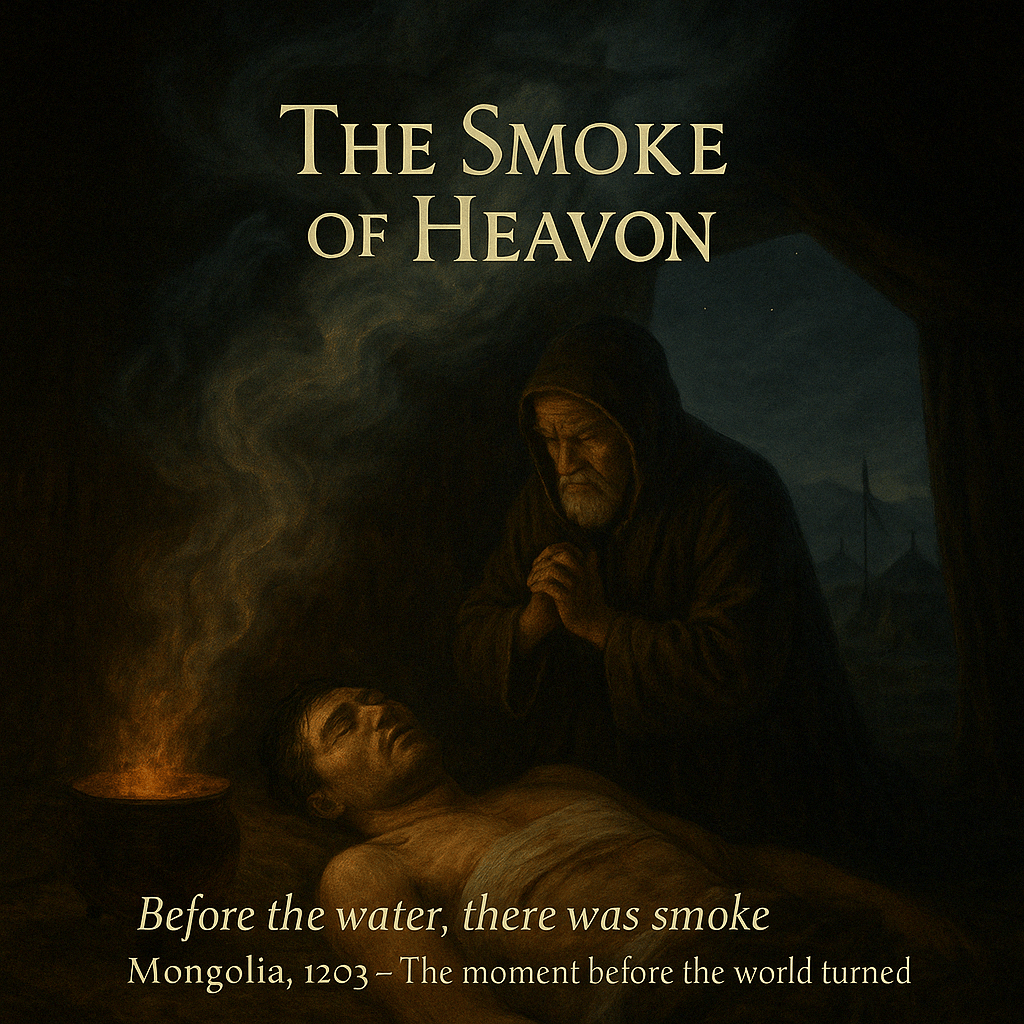

The old shaman murmured prayers over the smoke, letting the curls of burning juniper rise toward the sky, carrying words he no longer fully believed in.

Outside the ger, the great Khan lay wounded.

Temüjin’s side was bandaged in rough cloth stained rust-red, the spearhead still lodged deep in the meat of his ribs. His breath came hard. He had not risen since the Naiman ambush three days past. He had spoken little since Wang Khan, his once-father in friendship, had betrayed him at the pass near Erdene. The camp murmured: would Temüjin live? If he died, who would unify the tribes? What would become of the dream?

And it was into this haze of blood, fire, and uncertainty that the Nestorian priest came.

1. Between Heaven and Earth

His name was Mar Qasra, a pale-skinned man from far-off Samarqand who had ridden with the Keraites for years. To most, he was just another foreign monk with strange robes and even stranger words. But to Sorghaghtani—Temüjin’s young sister-in-law and daughter of the powerful Keraite Christian prince—he was more than that. He was a man of wisdom, of stories, of power that did not come from the sky or the mountain, but from the Book.

Temüjin had once laughed at that.

But now, as fever took his body and the shamans’ chants did nothing, Mar Qasra was allowed inside the Khan’s tent.

The priest said nothing, only laid a small wooden cross beside Temüjin’s head and began to pray—in Syriac, then in faltering Mongolian. He spoke of suffering. Of a man nailed to wood for the sins of others. Of a kingdom not of yurt and horse, but of spirit and light.

Temüjin stirred.

He asked, on the third day, “What kind of god lets himself be killed?”

Qasra replied, “The kind who knows that power is not just in strength—but in sacrifice. In law. In unity.”

2. The Politics of God

When word spread that the Khan had taken interest in the Christian priest, voices rose quickly.

Bo’orchu, his loyal friend and general, muttered that this was foolishness. Subutai listened, calculating. Hoelun, Temüjin’s mother, furious and old, warned that this was a foreign faith—and that abandoning the Sky Father would curse the clans.

But others saw opportunity.

The Keraites, Christian for two generations, offered greater support in exchange for the elevation of their faith. Merchants from the Silk Road favored a universal law that would smooth the tangle of tribal customs. Educated Uyghur scribes promised that the Book could be translated, could be taught, could bring unity to the newly conquered.

Temüjin understood something deeper: Tengrism had served him—but it was bound to the earth, to place, to lineage.

Christianity… offered universality.

To rule all the tribes, he would need more than lineage. He would need a claim from Heaven.

3. The Baptism

The spring thaw had come late. Snow still lined the crests of the hills above the Onon River. The air was cold, bright, and sharp.

The yurts were arrayed in a great ring, the banners of a dozen tribes fluttering. Murmurs rose like insects from the gathered chiefs: Keraite, Merkits, Tatars, even some Naimans.

Temüjin stood, still bandaged, but tall. He had bathed in the icy water and emerged reborn—not as a tribal warlord, but as Khagan, appointed not only by conquest, but by God.

He knelt before Mar Qasra beside a great basin of water blessed in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Qasra poured water over the Khan’s head, speaking in broken Mongolian:

“Temüjin, in the name of Eshūʿ (Jesus), you are cleansed and made new.”

A hush fell.

Then, from the crowd, a cry: “Tengri has spoken!”

The priests of the old ways remained silent. But they did not protest.

The smoke of juniper still curled in the air, but now it mingled with the scent of frankincense, rising from a silver censer held aloft by a Keraite bishop in green robes.

4. The Aftermath

Temüjin took the name David, though few called him that. He kept his sword sharp and his justice brutal. But something shifted.

His banners bore the cross of the East, and his messengers carried gospels along with law decrees. He still demanded loyalty—but now he spoke of brotherhood, of law, of the world as a thing to be shepherded, not simply conquered.

To the Mongols, he was still the son of the blue wolf.

To the Christians, he became the anointed one of the steppe.

And to history, in this altered world, he became the hinge upon which the old world turned into something entirely new.

Leave a comment