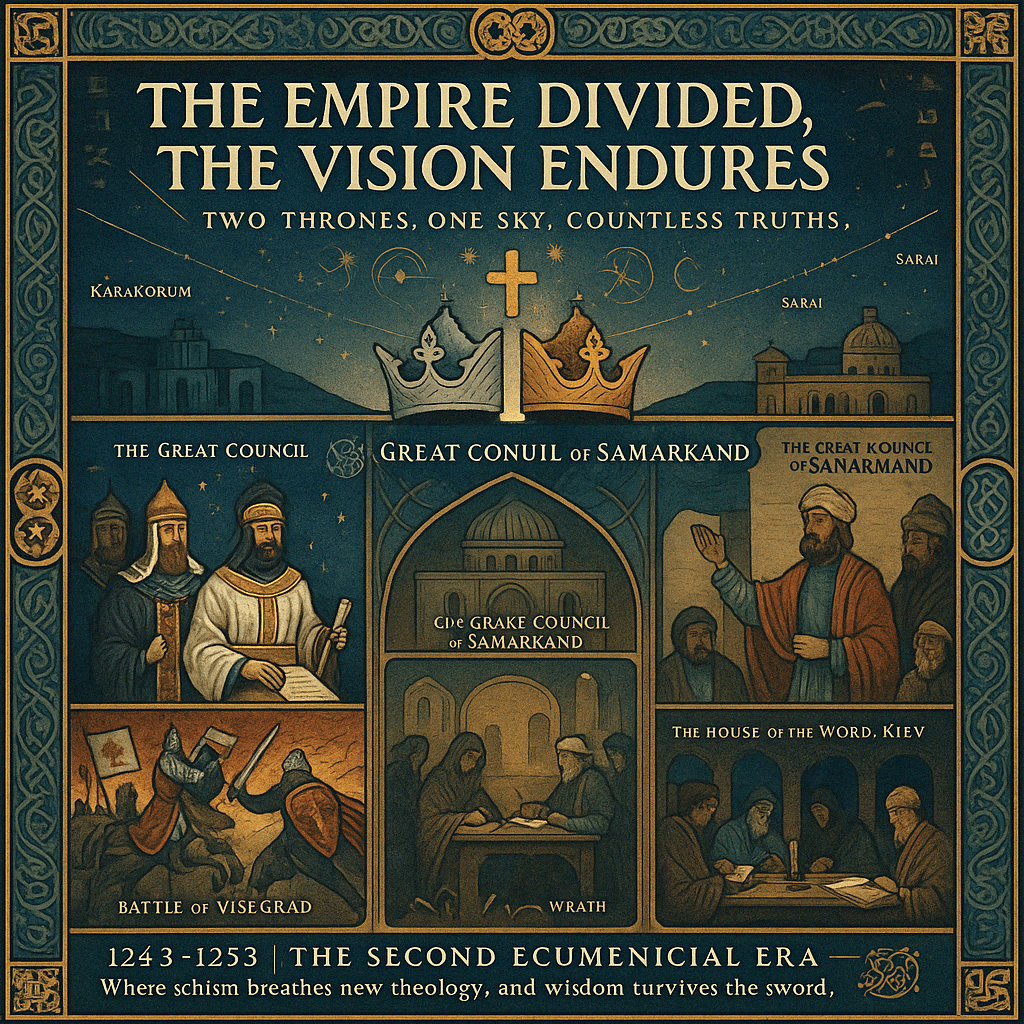

Following the death of Ögedei-Elias in 1243, the question of succession triggers the empire’s first crisis of religious legitimacy. The khaganate, deeply tied to its Christian identity, must now choose not just a new ruler—but a new spiritual direction.

Two candidates emerge:

- Guyuk-David, son of Ögedei, a pious and fiery advocate of a more aggressive Nestorian theocracy.

- Batu-Thomas, the son of Jochi and ruler of the western ulus (roughly modern Russia and Central Asia), who favors a pluralist, pragmatic model—more tolerant of Muslims and Orthodox Christians, and more focused on secular governance.

What unfolds is not full-scale civil war, but a deeply political—and theological—cold schism that echoes across continents.

Key Developments, 1243–1253

👑 1. The Great Schism of Karakorum (1244–1246)

The Kurultai of 1244

- At the gathering in Karakorum, the empire’s high clergy and generals are split.

- Nestorian hierarchs support Guyuk-David, citing divine succession and stricter orthodoxy.

- Turkic nobles, Uyghur scribes, and Muslim advisors from the west back Batu-Thomas, who promises to keep the peace among faiths.

- After a tense series of deliberations—and the sudden death of a key archbishop (under mysterious circumstances)—Guyuk-David is declared Khagan in 1245.

- Batu refuses to attend the enthronement, retreating to Sarai, the capital of the western ulus, where he establishes a parallel court. He does not renounce loyalty—but also does not recognize Guyuk’s spiritual authority.

This marks the beginning of what becomes known as the Dual Thrones Period (1245–1260).

🏰 2. The Second Ecumenical Council of Samarkand (1247)

Attempting to heal the divide, bishops from across the empire gather in Samarkand, under Batu’s protection. The goal: create a unified Christian legal and theological framework that can bridge the eastern (Nestorian) and western (Orthodox and Latin) worlds.

Key participants:

- Nestorian bishops from Karakorum and Seleucia-Ctesiphon

- Armenian Catholicoi and Byzantine representatives from Nicaea

- A cautious observer from Rome (Dominican friar Brother Hugo of Provence)

Key outcomes:

- The Doctrine of the Four Natures is proposed: an attempt to harmonize Christological differences by invoking a steppe cosmology—divinity and humanity, wisdom and action.

- A new liturgical calendar is introduced, merging Mongol seasonal festivals with Christian holy days (e.g., the Feast of the Sky-Born Word in spring).

- A joint resolution is passed calling for the recognition of multiple patriarchates, echoing early church models.

But Karakorum’s Nestorian hierarchy refuses to endorse the council’s outcomes. The schism deepens.

⚔️ 3. Wars of the Borderlands (1246–1253)

Resistance in Europe

- In Bohemia, Hungary, and Poland, anti-Mongol movements gain strength, fueled by Rome’s increasing hostility to Mongol Christianity.

- The Papal Crusade of 1248, declared by Pope Innocent IV, sends French and German knights to “liberate Christendom from the heretical yoke of the Mongols.”

- Mongol-Christian forces, under Batu-Thomas, repel the crusaders at the Battle of Visegrád (1250), but the campaign convinces Batu to consolidate his authority over Eastern Europe.

Uprising in the Abbasid Sphere

- In Baghdad and Isfahan, Muslim scholars begin organizing an intellectual resistance to Mongol-Christian oversight.

- A poet and jurist known as al-Kazwini writes the influential Refutation of the Four Thrones, critiquing the empire’s theocratic pluralism.

- In response, Guyuk orders the exile of several Muslim scholars from Karakorum, leading to a quiet purge in 1252.

📚 4. The Rise of Eurasian Humanism

Despite these tensions, the empire experiences a renaissance of cross-cultural knowledge, especially in the western cities.

The House of the Word – Kiev (1249)

- Under Batu-Thomas’s patronage, the first trilingual university is founded in Kiev, offering education in Syriac, Slavic, and Arabic.

- Mongol engineers, Byzantine mathematicians, Jewish astronomers, and Persian poets work side by side.

- Texts from China, India, and Rome are translated into a new universal script developed from Uyghur-Mongol cursive and Syriac vowels.

New Theology Emerges

- A generation of theologians and philosophers begins blending Confucian ethics, Christian eschatology, and steppe legalism into what is now called the Doctrine of the Way-Born King—a vision of rulership based not just on blood or baptism, but on harmony with cosmic law.

⛪ 5. Death of Guyuk-David (1253)

The decade ends with the death of the sitting Khagan, Guyuk-David, from illness—some say poison, others divine punishment.

His death opens the door to reunification—or greater fracture.

A new kurultai is called for 1254. Batu-Thomas begins his long journey east.

Summary of 1243–1253: The Empire Divided, the Vision Endures

This decade sees the Mongol Christian Empire at its spiritual and territorial zenith, but also on the brink of collapse from within. Its ideals—universal law, pluralist Christianity, the fusion of East and West—are challenged by:

- Doctrinal rivalries between high Nestorianism and Eurasian humanism.

- Political fragmentation between Karakorum and Sarai.

- External pressures from Rome, Sunni scholars, and nationalist insurgents.

And yet—no empire on Earth commands such prestige, hosts such diversity, or offers such a compelling vision of civilization under God’s sky.

Leave a comment