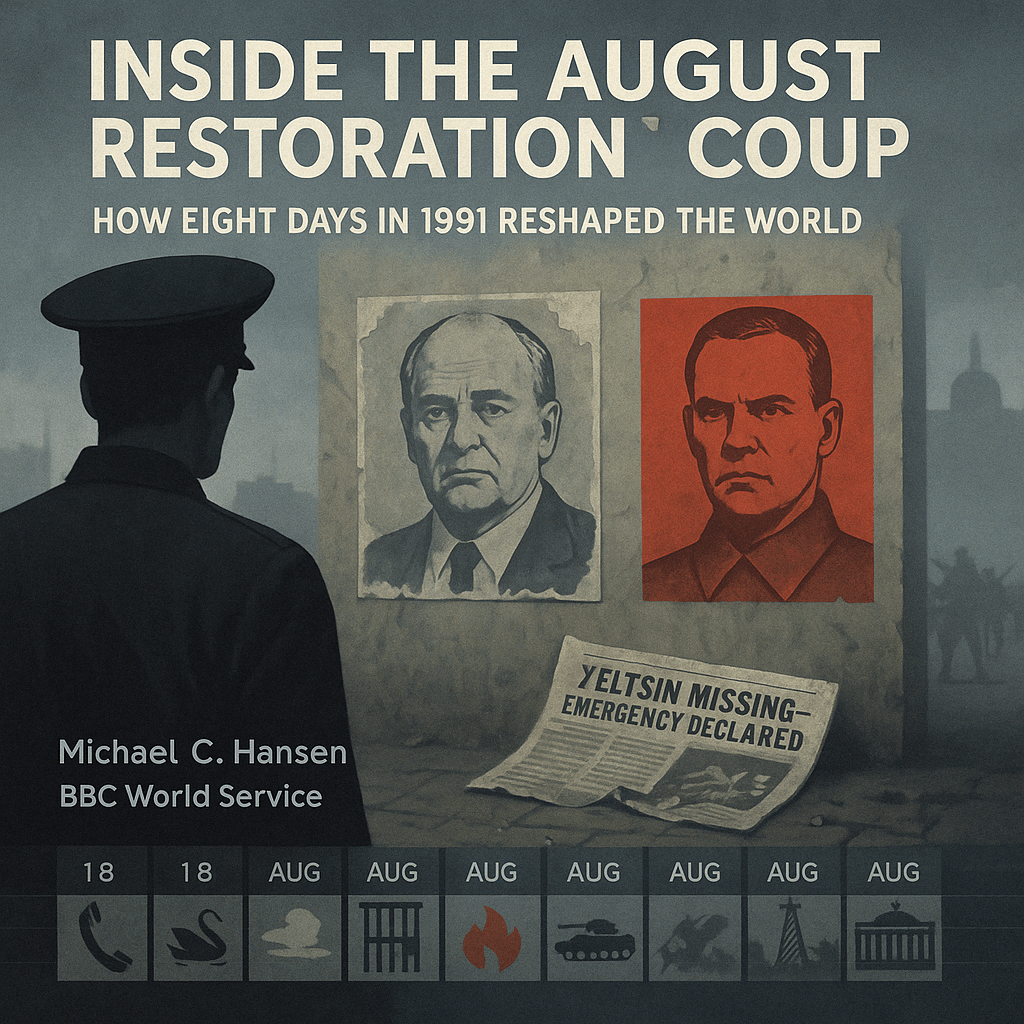

How Eight Days in 1991 Reshaped the World

By Michael C. Hansen – Foreign Affairs Correspondent, BBC World Service

Filed: August 2021 (30-year retrospective)

Moscow, August 1991.

I remember the sky first—blank and steel-colored. The kind of sky that seems to press downward. Heavy. Like something was about to fall.

In retrospect, it did.

📅 August 18, 1991 – The Isolation of Gorbachev

On the evening of August 18th, Mikhail Gorbachev was cut off at his Crimean dacha, officially due to “illness.” In truth, he was placed under house arrest by a coalition of hardline officials from the Communist Party, the KGB, and the military—self-styled as the State Committee on the State of Emergency (GKChP).

Key Players:

- Gennady Yanayev – Soviet Vice President, made acting head of state.

- Dmitry Yazov – Defense Minister, mobilizer of armored divisions.

- Vladimir Kryuchkov – Chairman of the KGB, architect of surveillance operations.

- Valentin Pavlov – Prime Minister, economic hardliner.

These men had concluded that Gorbachev’s reforms—perestroika, glasnost, and the proposed Union Treaty—had gone too far. In their words:

“The homeland is crumbling under the pretext of democracy.”

Gorbachev refused to resign. The GKChP cut all lines of communication.

📅 August 19 – Coup Declared, Tanks in Moscow

At 6:00 AM, Soviet state media announced a state of emergency.

Martial law. Curfews. Political gatherings banned.

All programming on television was replaced with Swan Lake—a subtle, almost mocking signal that a new era had begun.

Tanks rolled into Moscow. Armored divisions surrounded the White House (Russian Federation Parliament building), where Russian President Boris Yeltsin was expected to resist.

He never got the chance.

By 8:15 AM, Yeltsin was detained en route to a meeting with supporters. Early reports said “questioned.” Later sources confirmed he was executed that afternoon in Lefortovo Prison.

The news was not reported until days later.

Instead, Soviet television showed Vice President Yanayev, visibly trembling, announcing that he had taken power to preserve order.

The city held its breath.

📅 August 20 – The Crackdown Begins

Protests began forming across Leningrad, Kiev, and Tallinn. In Moscow, a crowd gathered near the White House by mid-morning. Chants of “No to dictatorship!” echoed across the plaza.

But resistance was disorganized. The leadership was gone. Communications were jammed. Western journalists were corralled in hotels, unable to move freely.

At 3:40 PM, a column of tanks opened fire on demonstrators near Pushkin Square. Twelve were killed. Hundreds detained. That night, electricity in parts of Moscow was cut.

Across the country, newspapers ceased printing. Radio Free Europe was jammed. The Vremya news program listed dissident names, calling for them to report “voluntarily for inquiry.”

📅 August 21 – The KGB Moves In

The VUGB (the renamed KGB internal division) began what they called “Operation Harmony”: the preemptive detention of potential opposition. Over 8,000 arrests were made in 48 hours.

Targets included:

- Journalists

- University professors

- Local reformist leaders

- Jewish cultural organizers

- Members of banned political clubs

The prisons filled. The trains filled. Siberia reopened.

That night, the first instance of “ideological emergency re-education centers” was announced. Gorky and Khabarovsk became sites of early internal exile.

📅 August 22 – Gorbachev Speaks, Then Disappears

On August 22nd, the GKChP released a short video of Mikhail Gorbachev, smiling weakly and endorsing the new emergency government.

His voice was flat. His eyes dull.

Some said it was coerced. Others said he had given up.

That was the last time he was seen publicly. He was moved to a dacha near Sochi and placed under “permanent ideological supervision.” He would die in obscurity a decade later.

📅 August 23–25 – The Fall of Reform

By August 23rd, most republic leaders had pledged allegiance to the GKChP. Exceptions—like Lithuania, Georgia, and Ukraine—were met with force:

- Tbilisi: 78 protesters killed in street clashes.

- Vilnius: Media tower stormed. Government deposed.

- Kiev: Parliament dissolved. Ukrainian Popular Movement leaders arrested.

Soviet tanks were back on Baltic streets. The Iron Curtain had never fallen—it had just rusted briefly.

In the West, President Bush called the coup “a profound tragedy.” Sanctions were discussed. But with nuclear forces under Yazov’s control, no one dared intervene.

📅 August 26 – The Restoration Declaration

The GKChP announced the formation of a “Transitional Sovereign Soviet Authority”, claiming to uphold Leninist principles, protect national unity, and “guide the Union back to ideological health.”

The Communist Party, which had briefly splintered, was restored as the only legal political body.

A new figure emerged: Colonel Ivan Gromov, a KGB security officer who had overseen Moscow’s pacification. He was named Chairman of the Supreme Committee for the Salvation of Socialism—a temporary title that would, over the next decade, become permanent.

His face was hard. Unsmiling. Unapologetic.

When asked by a Western reporter what message he had for the people of Moscow, he replied:

“You will thank us. Not today. But when your children have bread.”

🔍 Immediate Outcomes (August–December 1991)

| Domain | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Politics | Reformist officials removed or arrested. Local soviets restructured. Autonomy revoked. |

| Media | Replaced with state organs. Foreign correspondents expelled. |

| Economy | Privatization halted. Industries re-nationalized. Price controls reimposed. |

| Society | Demonstrations banned. Passport internal controls reintroduced. Blacklist system revived. |

| Military | Strategic missile command placed under emergency readiness. Doctrine shifted to “ideological deterrence.” |

📝 Final Reflection: What Was Lost in Eight Days

In those eight days—August 18 to August 26—an entire historical path was sealed off.

The post-Soviet dream of liberalization died with the silence of Gorbachev, the arrest of reformers, and the bullet that silenced Boris Yeltsin.

From the West, we watched.

Stunned. Then worried.

Then—eventually—accustomed again to the old Cold War language.

But inside the USSR, the effect was spiritual.

One Russian writer, exiled in Paris, put it best in a smuggled letter:

“It was as if a door had opened. Not to the West, but to ourselves. And just when we glimpsed who we could become—we were told to forget.”

History did not end in 1991.

In this version, it began again—wearing a harder face.

Leave a comment