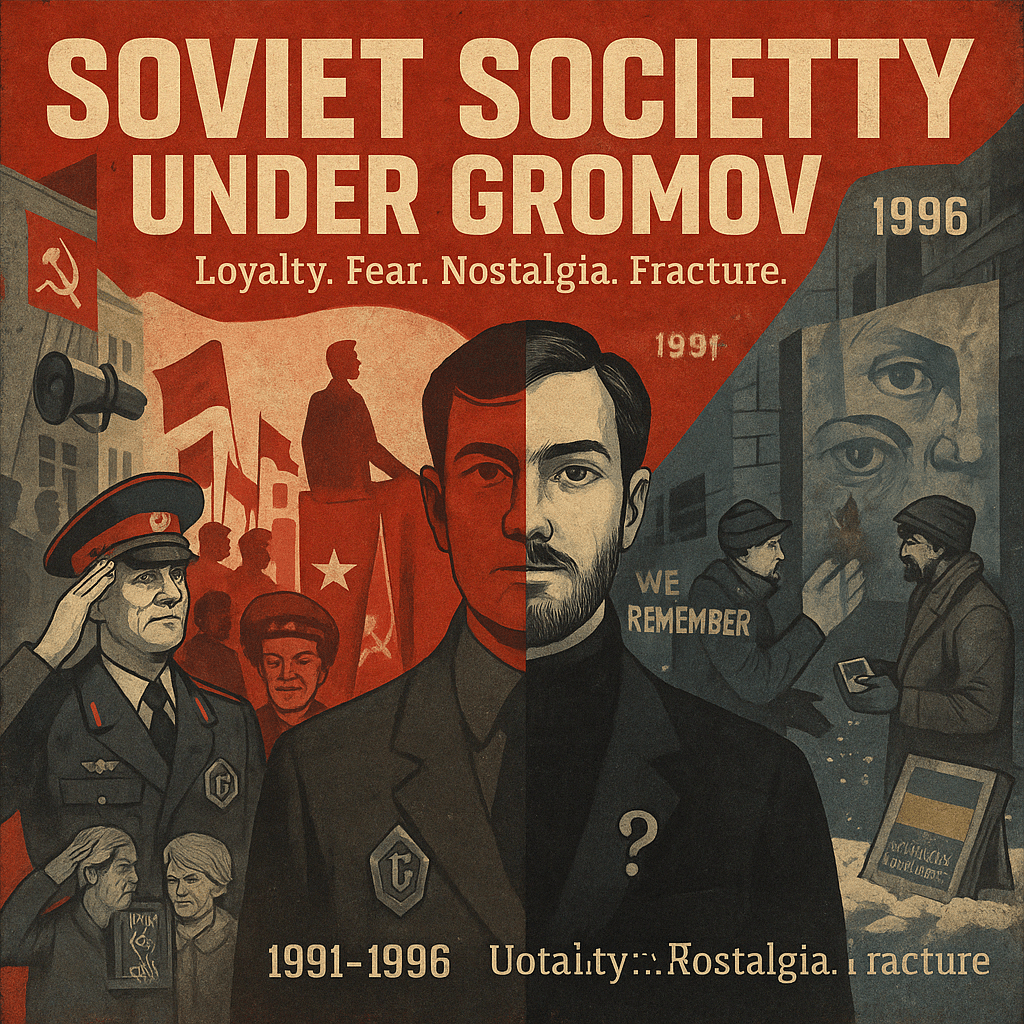

A Study in Loyalty, Fear, Nostalgia, and Fracture

🟥 Supporters of the Restoration

These groups actively supported or at least publicly accepted the return of authoritarian socialism. But their support was layered: some from belief, others from fear, many from bitter experience of the chaos before.

1. Old-Guard Party Cadres and Bureaucratic Elites

Who they were:

Middle-aged to elderly men and women who had risen under Brezhnev, now revived from political retirement. Regional apparatchiks, factory directors, union bosses, defense sector managers.

Why they supported it:

They had been sidelined under Gorbachev, afraid of the vacuum his reforms created. Gromov’s restoration promised stability, hierarchy, and the return of the Party’s divine right to rule.

Cultural Symbols:

- Dark gray Party pins reissued with Gromov’s initials engraved subtly beneath the hammer and sickle.

- Offices re-decorated with portraits of Lenin, Gromov, and Stalin—the “Unbroken Line.”

- Red directive banners reading: “THE PARTY FALTERED. NOW IT STANDS AGAIN.”

Rhetoric:

“We do not apologize for order.”

“History bent—but now it is straightened.”

2. KGB/VUGB and Internal Security Officers

Who they were:

The security class—field agents, analysts, internal informants, ideological monitors, prison camp officers. Many had been marginalized or demoralized in the late ’80s.

Why they supported it:

Gromov was one of their own. They were given resources, prestige, and a sacred mission: root out “ideological contamination.”

Public Presence:

- Patrolling in black greatcoats with crimson armbands reading ЧИСТОТА (“Purity”).

- Posters showing a VUGB officer shielding children from Western “decay”—depicted as a many-eyed, blue-lit monster.

- Campaigns like: “Your silence is loyalty. Your watchfulness is patriotism.”

Slogans:

“THE ENEMY DOES NOT SLEEP.”

“TRUTH NEEDS TEETH.”

3. Rural Populations and the Elderly

Who they were:

Collective farm workers, small-town pensioners, war veterans—those who remembered bread lines, ration books, and Khrushchev’s dithering with cold resentment.

Why they supported it:

Gromov promised subsistence and structure. For them, chaos was not liberation—it was existential risk. The Restoration revived food programs, military pensions, and rail discounts.

Imagery:

- Trains and buses with “FOR MOTHERLAND AND STABILITY” scrawled in red.

- Local markets renamed “Soviet Provision Points” with ration cards reissued.

- National holiday for pensioners established: “Day of the People’s Endurance”.

Common sayings:

“He brought back meat.”

“I’d rather be watched than starve.”

4. Ethnic Russian Nationalists

Who they were:

Not all were Marxists. Some were Orthodox revivalists, military romantics, or young men drawn to imperial nostalgia.

Why they supported it:

They equated the USSR with Russian pride. The humiliations of the West during Gorbachev’s time were now reversed. The Soviet flag meant greatness, revenge, and resurgence.

Visual Culture:

- Street murals of Soviet cosmonauts weeping over the broken USSR—restored with Gromov’s silhouette holding a torch.

- Dual flags: Soviet red crossed with Saint George’s Orthodox cross—symbolizing the strange blend of old Communism with Russian mythic nationalism.

Slogans:

“A RED EMPIRE IS STILL AN EMPIRE.”

“GROMOV: THE RUSSIAN IRON.”

“NO MORE DECADENCE. NO MORE SHAME.”

🟦 Opponents of the Restoration

These were the silenced voices. Most did not resist openly—they adapted, whispered, or fled. But they represented a different vision of the USSR: democratic, open, post-ideological. Gromov called them “soft enemies.”

1. Urban Liberals, Students, and Reformists

Who they were:

Educated classes in Moscow, Leningrad, Kiev. Former journalists, literature professors, software engineers, economists who had flirted with Western ideas.

Why they opposed it:

They had tasted freedom—the ability to publish, travel, joke. Now it was gone. Their radios jammed. Their email filtered. Their friends “reassigned.”

Signs of Resistance:

- Underground poetry circles, ironic performance art in back alleys, flash graffiti in metro stations: “GROMOV IS A STATUE. WE ARE RAIN.”

- Black market recordings of Pink Floyd, Nirvana, and Mikhail Bulgakov audiobooks circulated on cassette.

Dress Code:

- Black turtlenecks, Czech trench coats, pins shaped like question marks or cracked hourglasses.

Slogans (whispered, not shouted):

“WE REMEMBER.”

“THE SNOW MELTED ONCE. IT WILL AGAIN.”

2. National Minorities and Peripheral Republics

Who they were:

Ukrainians, Estonians, Georgians, Armenians, Tatars, Kazakhs—who had seen independence in reach before the coup crushed their hopes.

Why they opposed it:

They now faced Russification, surveillance, and the suppression of their languages and cultures.

Acts of Defiance:

- Secret schools in basements where children learned banned alphabets.

- Folk songs sung in code: upbeat in tone, mournful in meaning.

- Religious holidays celebrated behind blacked-out windows.

Visual Symbols:

- Ukrainian blue-and-yellow stitched into the lining of coats.

- Georgian crosses hidden in belt buckles.

- Graffiti: “THE USSR IS A PRISON. OUR SPIRIT IS NOT A CELL.”

3. Young Urban Professionals and Cultural Westernizers

Who they were:

The so-called “MTV Generation”—people in their 20s and 30s, fluent in English, raised on the edge of Western influence.

Why they opposed it:

They had planned to leave. To start startups, get scholarships, join the world. Now their passports were frozen, their music banned, and their future algorithmically reassigned.

Cultural Icons:

- Faux-foreign cafés raided for “ideological contamination.”

- Black-market Levi’s and Walkmans traded in the same alleys as illicit vodka in the 1980s.

They wrote slogans in English—to practice, and to distance:

“BORDERS ARE LIES.”

“THE WALL IS BACK. THIS TIME, IT’S INVISIBLE.”

4. Dissidents of the Eastern Bloc

Who they were:

Polish Solidarity veterans. Czechs from the Prague underground. East Germans who had walked out into the West.

Why they opposed it:

They saw the coup as a betrayal of history. Many had allies in Soviet reformist circles—now arrested or “vanished.”

Survival:

- Some fled to Vienna, Berlin, or Helsinki.

- Others stayed, smuggling information, hiding texts, teaching counter-history.

Icons of Resistance:

- Hidden busts of Václav Havel and Lech Wałęsa.

- Messages in toothpaste scrawled under bathroom mirrors.

Their warning:

“WHEN THE RED RETURNS, THE NIGHT IS LONGER.”

🪖 The Military: Fragmented Allegiance

- High-ranking generals favored Gromov.

- Middle and junior officers were split, often sympathetic to reformists, especially in the border republics.

- Some units were quietly purged after “hesitating” during the coup.

Military Propaganda Imagery:

- Posters of Gromov on horseback in the style of Alexander Nevsky, facing down a hydra labeled ‘Liberalism, Nationalism, Capitalism.’

Slogan used in parades:

“NOT JUST STEEL. RED STEEL.”

Final Texture: What Society Looked Like (1992–1995)

- Loudspeakers returned to factory floors, playing state-approved news and patriotic marches.

- Giant murals painted over 1980s advertising boards: “GROMOV RESTORED WHAT THE WEST CORRUPTED.”

- Swan Lake played again—not just during emergencies, but at train stations and post offices.

- Schools taught history not as fact—but as formula: Lenin + Stalin + Gromov = Eternity.

- People learned to smile with closed lips.

To whisper instead of shout.

To remember that silence was not submission—it was survival.

Leave a comment