In 1983, China was already a country in motion — but it was motion like a slow, heavy river, not a mountain stream.

The reforms Deng Xiaoping had set in motion after 1978 were loosening old bonds, opening markets, letting people plant what they wished, sell what they grew. In the south, you could smell the faint salt of the world beyond; foreign goods, foreign words, foreign dreams seeped in through Shenzhen and Guangzhou.

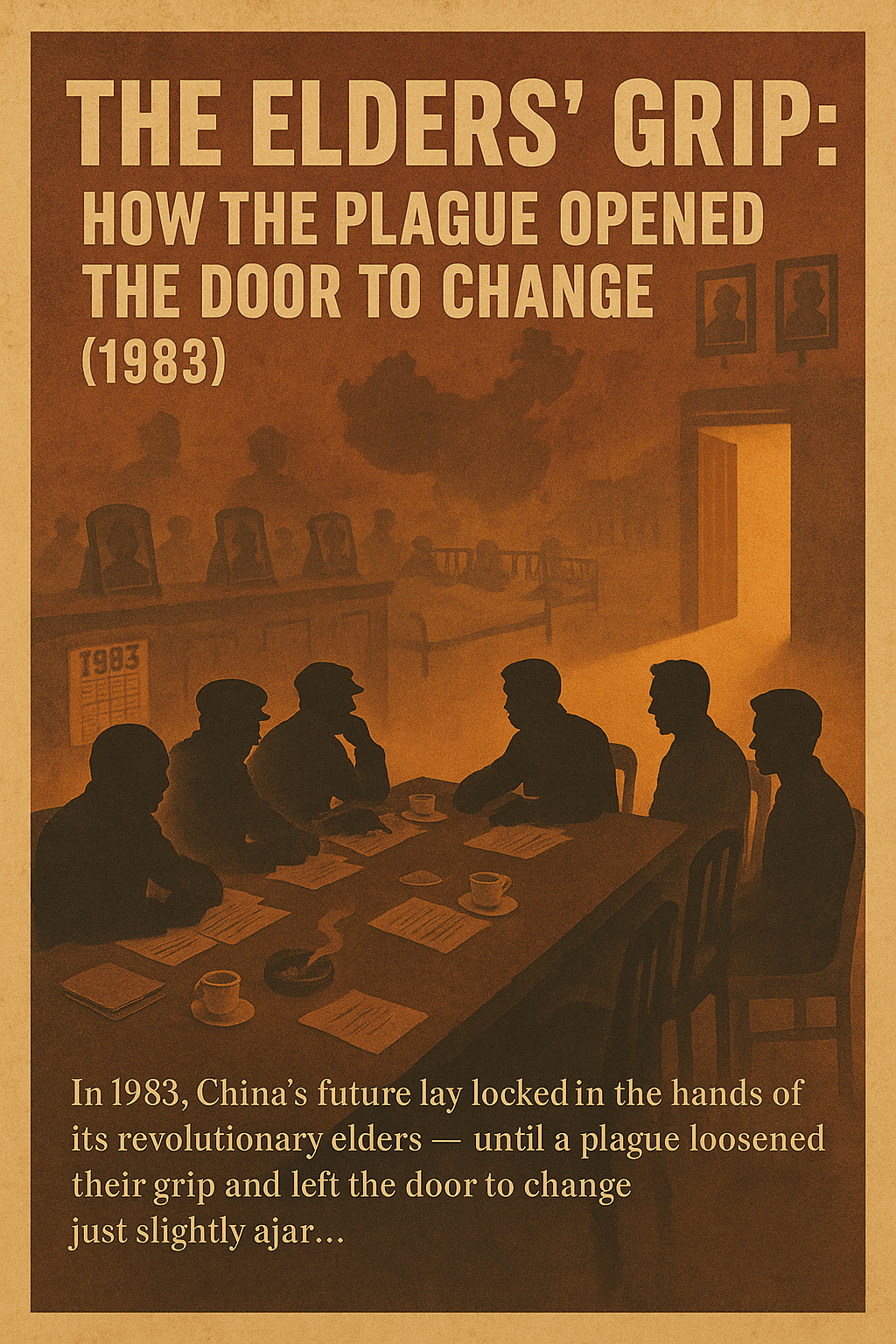

But in Beijing, in the rooms where real decisions were made, the air was thick and unmoving.

The men who truly held the reins were not just the ones with titles — they were the elders, the survivors of the Long March and the civil war, the veterans of the revolution. Many no longer held official posts, yet they could call in a minister with a word, stall a policy with a frown.

China’s political culture gave them this grip. In a land that revered age and the wisdom of survivors, it was almost unthinkable to simply retire and fade away. Here, power and life were welded together — to the last breath, a man could still be a force in the capital. For the younger reformers like Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang, this was the quiet wall they faced every day. The reforms they wanted were not impossible — but they had to pass through rooms where men with fading eyesight still saw themselves as guardians of the revolution.

And then, the plague came.

It began far away — a terse cable from a Chinese embassy in Africa, a note in the Ministry of Health about a cluster of strange fevers. At first, the elders saw it as distant thunder. But by spring, it had crossed oceans, silent at first, then roaring through the streets. This was no ordinary illness; its fever burned hotter, its coughs tore deeper, its shadow fell heavier than any flu in memory.

In the halls of Zhongnanhai, it was merciless. Not all the elders were touched — but enough. Beds in elite hospitals filled with familiar faces. Portraits were draped in black crepe earlier than anyone had expected. And in the spaces they left behind, air moved where once it had been still.

For the first time in years, the younger men at the center of power looked around a meeting room and realized: the seats of resistance were fewer. Decisions would still be hard, bargains still bitter — but something had shifted.

It was a cruel way for change to come, and no one would call it a blessing. Yet in history, the door to the future is often opened by a hand none of us would choose.

And in the China of 1983, that door was now ajar.

Leave a comment