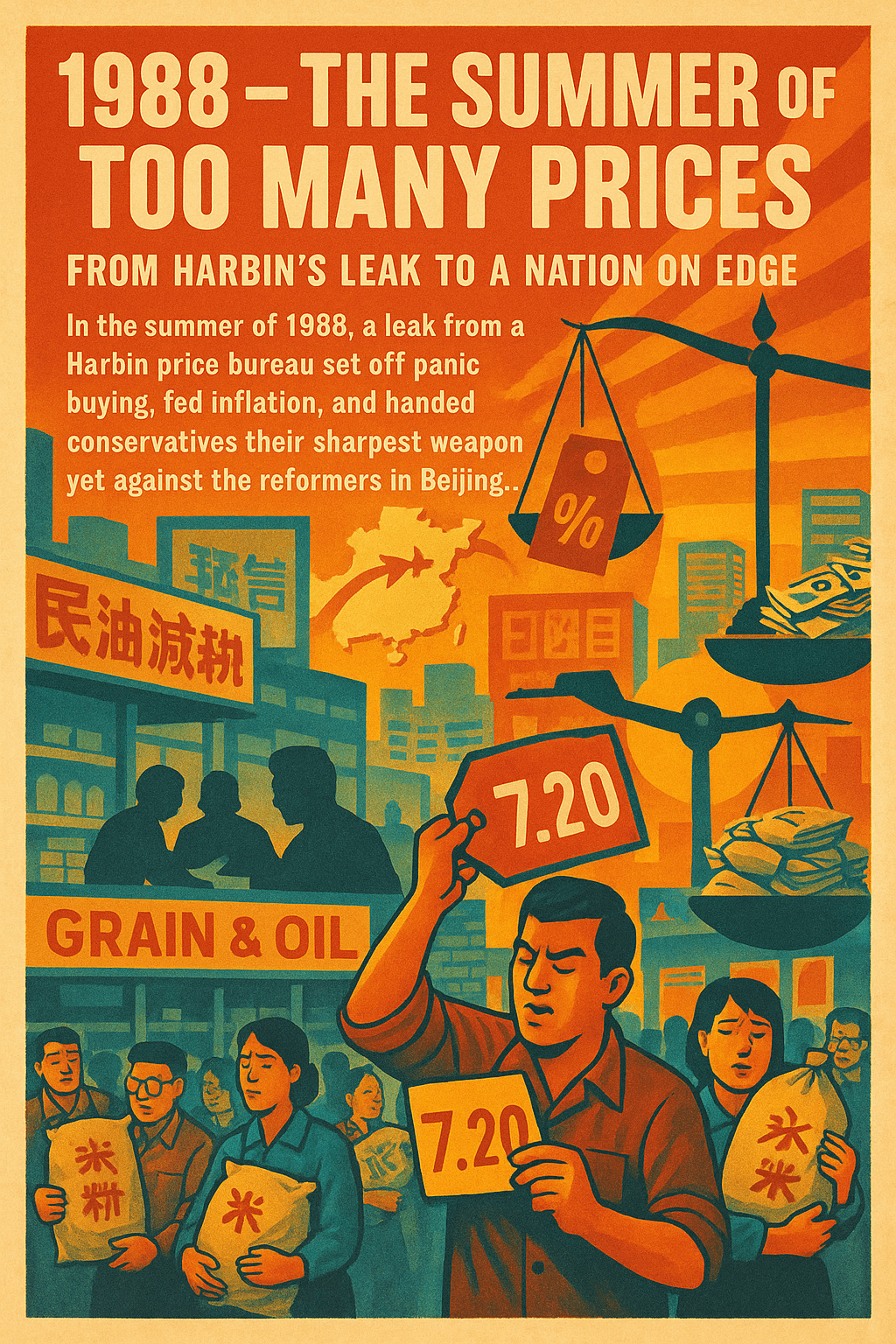

January 1988 – High tide for reform

With Hu Yaobang still in the General Secretary’s chair and Zhao Ziyang in charge of the economy, the year began on a wave of confidence. Coastal cities were booming. In Guangzhou, billboards for Japanese refrigerators and Hong Kong fashions were sprouting along main roads. Shenzhen had gone from fishing village to mini-Hong Kong in less than a decade, and now Shanghai was whispering about becoming an “international financial center” before the millennium.

The conservative elders still alive — Chen Yun fading, Wang Zhen grumbling, Bo Yibo playing middleman — were marginal compared to the combined Hu–Zhao–Deng axis.

But reform’s very speed was setting up trouble.

The mid-level accident: Harbin Price Bureau leak

In late March, in Harbin, a mid-level official at the municipal Price Bureau held a closed meeting with state-owned enterprise managers to explain an upcoming reform: price controls on certain consumer goods — meat, cooking oil, cloth — would be relaxed by 30% starting in August. The idea was to ease shortages and let supply catch up.

The meeting was not supposed to leave the room. But one of the attendees, an SOE deputy manager with a brother who owned a wholesale shop, told him to “stock up and prepare.” The brother told his suppliers. Within two weeks, black-market rumors in Harbin had morphed into “prices will double this summer”.

By April, the story had jumped provinces — not just in whispers, but in short-wave radio gossip, cross-border traders, and in the stalls of Shenyang’s morning markets. Housewives began buying up rice and cooking oil, fearing shortages.

Domino effect #1 – The urban panic buy

In May, Harbin, Shenyang, and parts of Beijing saw sudden spikes in demand for staples. Shops emptied shelves in hours. Official newspapers denied there was any price reform coming — which, as always, only confirmed for many that it was true.

Zhao Ziyang argued in the State Council that they should move the timetable forward to stabilize expectations: “If the public is already adjusting to higher prices, better to do it now and control the narrative.” Hu Yaobang supported him, arguing it would be “a test of our administrative skill.”

Deng Xiaoping agreed reluctantly, but with one caveat: “Keep rural prices steady. Do not make the countryside restless.”

Domino effect #2 – Provincial improvisation

Once Beijing gave the green light for earlier price reforms, provincial governments scrambled.

- Guangdong acted fastest, linking price liberalization to increased import quotas, which kept markets stocked and public anger minimal.

- Henan, slower to act, saw temporary shortages as speculators bought up flour and oil.

- Heilongjiang, where the rumor started, faced accusations from within the Party that “careless management” had caused panic.

In June, the Harbin Price Bureau director was quietly removed and reassigned to a research institute in Lanzhou — a political exile that sent a warning to other mid-level cadres.

Domino effect #3 – The ideological opening

The accident fed into existing urban frustrations:

- College students, already politically alert after 1986, began holding forums on “economic transparency.”

- Factory workers in two SOEs in Shenyang complained openly that “officials profit from inside information” — a phrase that made senior leaders nervous because it was only a few syllables away from corruption.

- In Guangzhou, a popular economics magazine ran an editorial on “information asymmetry” that was quickly pulled from newsstands but circulated in photocopied form on campuses.

Hu–Deng friction, summer 1988

By July, Deng Xiaoping was irritated. The reforms were right in principle, but the “Harbin leak” had shown him the danger of moving too fast without airtight discipline in the mid-ranks. He summoned Hu and Zhao to Zhongnanhai for what aides later called “the four-hour lecture.”

Hu argued that the incident proved the need for more openness, so rumors could be countered with facts. Deng replied, “Openness is fine, but gossip kills faster than truth heals. In war, you don’t tell the enemy your troop movements.” Hu knew Deng meant “the people” without saying it.

Still, Deng didn’t move against Hu — partly from the same logic as in 1987, partly from loyalty to their long-shared project of reform, and partly from the absence of a solid conservative replacement he trusted. Wang Zhen might have the stomach to oust Hu, but not the vision to keep the reforms alive.

By year’s end

- Inflation was running hotter than in our real timeline — nearly 15% in some cities by December 1988.

- Public grumbling was rising: urban households felt squeezed, while students talked more openly about accountability.

- Conservatives were quietly regrouping around Wang Zhen, arguing that the Harbin mess proved the dangers of “liberal” economic management.

- Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang were still in place — but now both carried political scars from the incident, and their reform program was walking into 1989 on thinner ice.

Key Political Figures – Late 1988 (Alternate Timeline)

| Name | Age (1988) | Faction | Position | Status After Harbin Incident | Notes & Background |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deng Xiaoping | 84 | Reform-leaning pragmatist | Chairman of CMC; Paramount Leader | Still ultimate arbiter; frustrated by mid-rank discipline failures | Balances reform speed with political control; loyalty to Hu keeps conservatives at bay. |

| Hu Yaobang | 73 | Reformist | General Secretary of CCP | Politically bruised but survived; reform program slowed | Advocates openness; uses Harbin as argument for more transparency; conservatives see him as reckless. |

| Zhao Ziyang | 69 | Reformist | Premier of the State Council | Shares blame for inflation; economic credibility dented | Pushes market reforms; tied to price liberalization decision after leak. |

| Wang Zhen | 78 | Hardline conservative | Vice President of PRC | Rallying point for conservatives; blames “liberal” economic management | Uses Harbin panic to rebuild conservative influence; cultivates younger allies in security apparatus. |

| Bo Yibo | 80 | Opportunist/Neutral | Vice Premier (Economic Affairs) | Avoided direct blame; still key deal-broker | Uses crisis to position himself as mediator; family continues to benefit from economic openings. |

| Chen Yun | 83 | Conservative economic planner | PSC Elder (semi-retired) | Frail but influential via memos; critical of rapid liberalization | Continues to promote “birdcage” economics from behind the scenes. |

| Peng Zhen | 86 | Centrist institutionalist | NPC Chairman | Pushes for stronger legislative oversight on economic reforms | Avoids open factional fights; focuses on procedural discipline. |

| Yang Shangkun | 81 | Military-leaning centrist | Exec. Vice Chair of CMC | Keeps PLA out of economic unrest | Trusted by Deng; ensures military neutrality during urban protests. |

| Li Peng | 60 | Younger conservative | Vice Premier (Infrastructure Oversight) | Still sidelined; uses crisis to warn of “loss of control” | Publicly loyal but privately maneuvering to regain conservative leadership position. |

| Li Ruihuan | 54 | Reformist rising star | Party Secretary of Tianjin | Strengthened by calm handling of price reform in Tianjin | Praised for pragmatic problem-solving; gaining popularity among workers. |

| Qiao Shi | 64 | Reformist pragmatist | Head of Central Organization Department | Oversees cadre discipline after Harbin | Trusted by Deng to fix mid-rank leaks without stalling reforms. |

Leave a comment