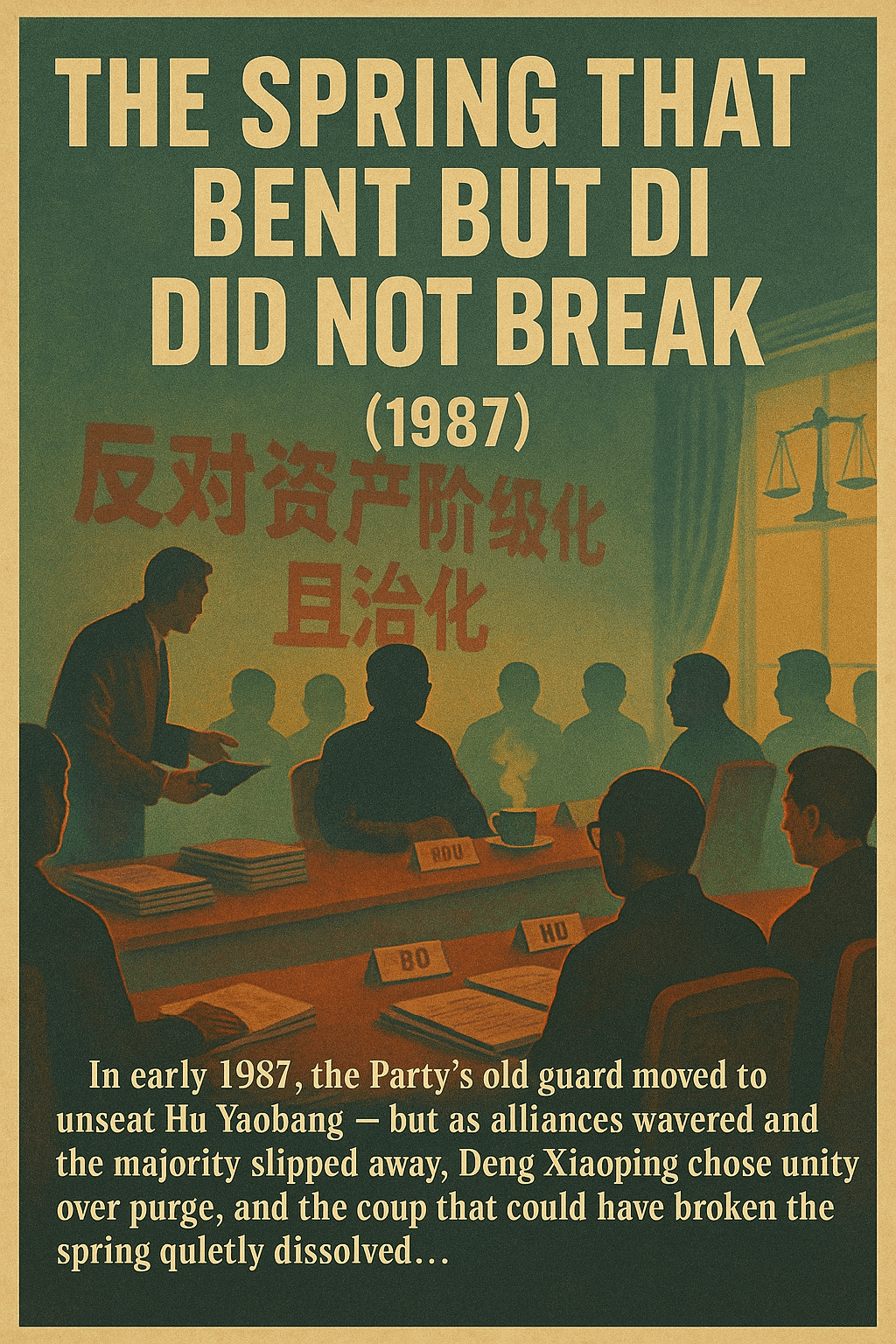

Huairen Hall, January 1987

The snow outside was the soft kind that muffled footsteps. Inside, the meeting room was overheated, the air thick with radiator steam and cigarette smoke. Curtains drawn tight, microphones dormant — this was a life meeting, not a public session.

The agenda’s title — On Strengthening the Struggle Against Bourgeois Liberalization — was ceremonial camouflage. Everyone in the room knew this was about Hu Yaobang.

In the weeks before, Li Peng had been moving quietly but decisively. He visited Wang Zhen twice, sharing notes on “ideological decline.” He stopped by Chen Yun’s home in Fuchengmen, listening to the elder’s wheezing voice warning of “letting go too far.” He met with two senior editors at Guangming Daily, hinting that more “firm voices” would be welcome in the papers.

Li understood the arithmetic of succession:

- Remove Hu → Zhao Ziyang becomes General Secretary → Premiership is vacant → Li Peng, as Vice Premier and conservative standard-bearer, is the logical choice.

His tone in these conversations was calm, but the calculation underneath was sharp.

Meanwhile, Bo Yibo was conducting his own reconnaissance. In early January, he visited Chen Yun and found him thinner, coughing until his eyes watered. Peng Zhen’s hands trembled when they poured tea. Deng Yingchao was absent from gatherings, pleading fatigue. The 1983 plague had taken its toll — the conservative phalanx was not at full strength.

Bo thought of 1985, when Deng had forced the old guard into “second-line” retirement. Back then, he had supported the plan — on the condition that their sons and protégés inherit the key positions. But now, watching Li Peng prepare to attack Hu head-on, Bo sensed a trap: without Chen Yun’s steady artillery and Li Xiannian’s gravitas, a purge could fail. And a failed purge would brand its architect as reckless.

Day One — The First Blows

Deng opened the meeting with a few perfunctory remarks about unity and vigilance, then signaled for Li Peng to speak.

Li rose, papers neatly stacked.

“Comrade Hu’s overindulgence toward certain mistaken trends has weakened our ideological defenses. Bourgeois liberalization has not been checked — in some cases, it has been encouraged. This is not a matter of style, but of political direction. If we do not act firmly, the Party’s leadership may be eroded from within.”

He named names: Fang Lizhi, “open-door” intellectuals, editors who had “misinterpreted” the Four Modernizations. He quoted Hefei students calling for “more Japan, less Soviet Union.” His delivery was clinical, each phrase a chisel blow.

Wang Zhen followed:

“When the dam cracks, you don’t stand and watch the water.”

It was sharp, but not the battering Li had counted on.

Bo Yibo’s Turn

In real history, this was where Bo would have led the seven-day siege — listing faults, demanding self-criticism until Hu could no longer stand.

Here, Bo looked around the table and saw the gaps. The unity of 1983 was gone.

“Every comrade makes mistakes,” Bo said evenly. “The important thing is to learn from them. Perhaps we need stronger mechanisms for guiding ideological work, so these gaps do not reappear.”

No humiliation. No cornering. Just enough to avoid suspicion, just enough to keep his hands free.

Backroom — That Night

After the session, Bo slipped into Deng’s study. They spoke with the ease of men who had once crossed rivers in the dark together.

Bo: “老邓,风要刮就刮小一点。房子还要大家住。” (If the wind must blow, let it blow small. We still have to live in the same house.)

Deng: “你是怕房子塌了?” (You’re afraid the house will collapse?)

Bo: “怕风大了,修房子的砖头都飞走。” (I’m afraid if the wind is too strong, even the bricks to fix the house will fly away.)

Bo left with no firm promise from Deng, but he had read the man’s silence: Deng was weighing, not charging.

Day Two — The Momentum Falters

The next morning, Peng Zhen took his turn:

“Unity is paramount. Any shortcomings should be corrected constructively, so as not to damage the cohesion of the Central Committee.”

It was a legalist’s speech — no blood in it. Even Wang Zhen, seeing the temperature drop, shortened his intervention.

Hu spoke in his own defense, voice steady:

“I take responsibility for any gaps in guidance. But our work has strengthened the economy, improved the people’s lives, and enhanced China’s standing in the world. If we close the windows completely, the air will grow stale.”

No defiance, but no surrender. Zhao Ziyang, when pressed, spoke only of “balancing reform and vigilance” — neither defending nor condemning Hu, but making clear he would not be Li Peng’s ally in this.

Backroom — Deng and Li Peng

On the third evening, Li was summoned to Deng’s residence.

Deng: “You think replacing Hu will solve the problem?”

Li: “We cannot let the Party drift, Comrade Xiaoping. Decisive action now will prevent greater loss later.”

Deng: “Without Chen Yun here to steady the left, without Bo pressing hard, this will split the team. And a split team can’t row the boat forward.”

Li left unsatisfied, but not yet defeated.

Day Four — Deng Ends It

Deng entered the room late, letting the murmur of conversation die before he spoke:

“同志们,团结是第一位的。不要为了一个人的缺点,影响整个队伍的合作。改革的路还长,大家都要在这条路上走下去。”

(Comrades, unity comes first. We cannot let one person’s faults disrupt the whole team’s cooperation. The road of reform is long; we must all walk it together.)

Silence. No vote was called. The meeting ended within the hour.

Aftermath

Hu Yaobang stayed in his chair. The anti-bourgeois liberalization campaign shrank into harmless study sessions and a few quiet transfers. Fang Lizhi was moved to a provincial university; liberal editors were “rotated” to less sensitive desks.

Li Peng was reassigned to “infrastructure oversight” — still Vice Premier, but effectively benched from the political front line. In the smoky tea rooms of Zhongnanhai, the phrase began to circulate: “Li bet on the wrong majority.”

Bo Yibo emerged untouched, his neutrality having bought him credit with both camps. Wang Zhen grumbled in private but said nothing in public. Chen Yun’s influence continued through memoranda, but his days of commanding the room were over.

And Deng — the last man in China who could end a storm with a single sentence — had shown he would not break the reformist keel to satisfy the conservative sails.

Key Political Figures – Mid-1987 (Post-Anti-Liberalization Campaign)

| Name | Age (1987) | Faction | Position | Status After Campaign | Personal Tie to Deng | Notes & Background |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deng Xiaoping | 83 | Reform-leaning pragmatist | Chairman of CMC; Paramount Leader | Undisputed arbiter; sided with Hu | N/A (central figure) | Balanced reform and unity; refused to break the reformist bloc for conservatives. |

| Hu Yaobang | 72 | Reformist | General Secretary of CCP | Survived attack; politically strengthened | Deng’s chosen political heir | Advocates political openness; gained leverage to appoint reform-minded provincial leaders. |

| Zhao Ziyang | 68 | Reformist | Premier of the State Council | Unharmed; influence over economic reform intact | Deng’s chosen economic reform executor | Careful not to openly defend Hu but ensured conservatives failed to remove him. |

| Li Peng | 59 | Younger conservative | Vice Premier (Infrastructure Oversight) | Sidelined; political momentum halted | Political “godson” to elder conservatives | Led attack on Hu; lost credibility without Chen Yun and Bo’s support. |

| Bo Yibo | 79 | Opportunist (now leaning neutral) | Vice Premier (Economic Affairs) | Preserved influence; no direct involvement in purge | Longtime ally in economic policy | Shifted to neutrality after assessing elders’ frailty; retains ties to both camps. |

| Wang Zhen | 77 | Hardline conservative | Vice President of PRC | Influence reduced without Chen Yun’s full backing | Fellow Long March veteran | Continued to oppose liberalization privately; more reliant on younger allies. |

| Chen Yun | 82 | Conservative economic planner | PSC Elder (semi-retired) | Frail health; influence via letters | Deng’s equal in revolutionary prestige | “Birdcage” economic theorist; unable to physically lead a purge. |

| Peng Zhen | 85 | Centrist institutionalist | NPC Chairman | Advocated unity; avoided factional extremes | Deng’s comrade from early Party years | Legalist; kept reforms within controlled legislative channels. |

| Deng Yingchao | 83 | Reform-leaning elder | NPC Vice Chairwoman | Absent from campaign; moral support to Hu | Widow of Zhou Enlai | Cultural and women’s rights advocate; respected across factions. |

| Yang Shangkun | 80 | Military-leaning centrist | Exec. Vice Chair of CMC | Stable; ensured PLA stayed neutral | Military ally | Key to preventing military involvement in the Hu–Li struggle. |

| Li Ruihuan | 53 | Reformist rising star | Party Secretary of Tianjin | Protected; positioned for future promotion | Promoted by Hu Yaobang | Popular for pragmatic governance; symbol of new generation. |

| Qiao Shi | 63 | Reformist pragmatist | Head of Central Organization Department | Role strengthened; managed cadre reshuffle | Trusted by Deng | Balanced appointments to avoid conservative backlash. |

Leave a comment