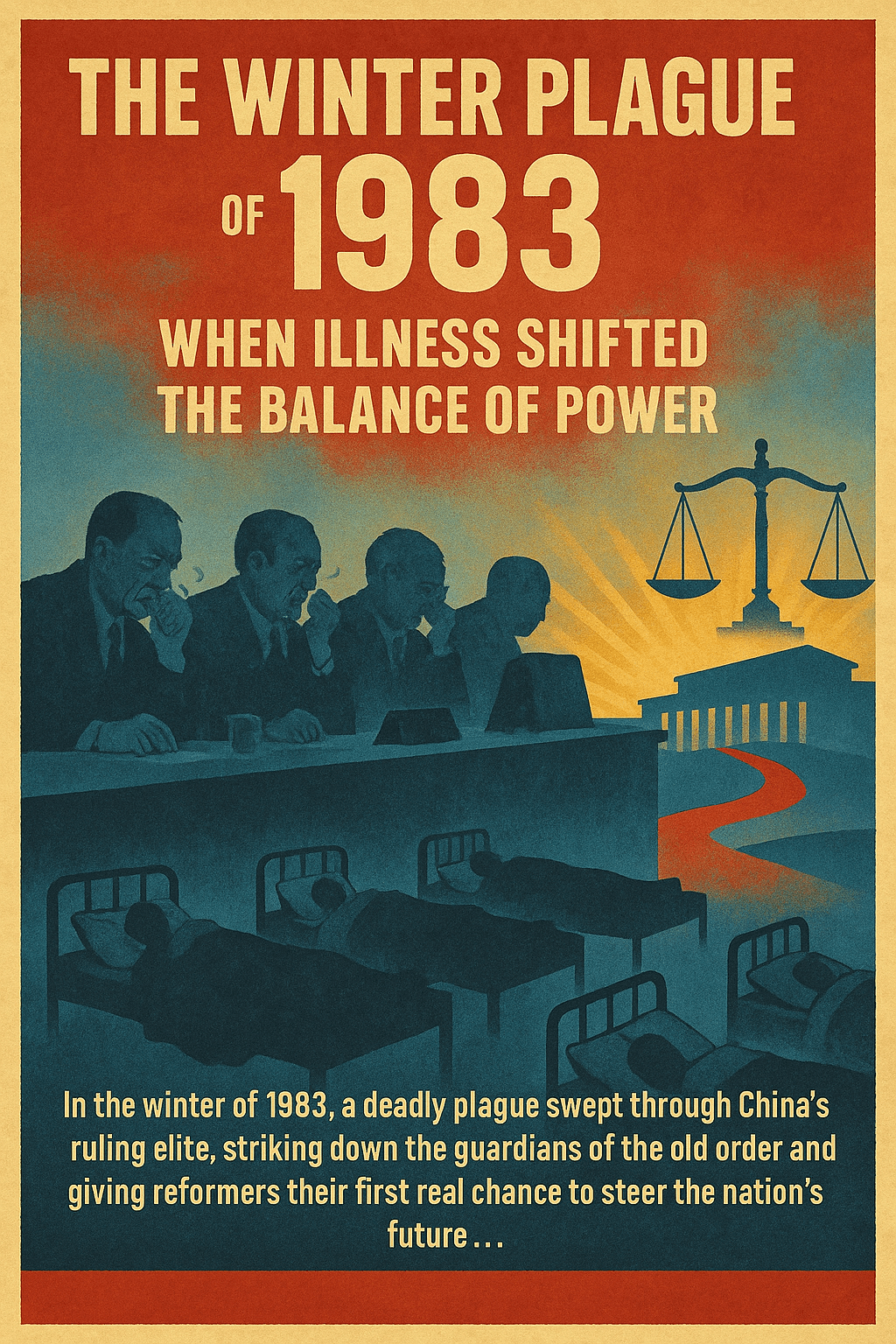

Excerpt from Red Spring, Broken Winter: China’s Unwritten 1980s (Fictional, 2025 Edition)

Prologue – January 1983

It began, as pandemics often do, far from the corridors of power. In a mining town outside Kemerovo in the Soviet Union, an unusually severe influenza-like virus — nicknamed The Black Winter Fever by local doctors — crossed into China via border traders in Manzhouli. By March, it had reached Beijing. Mortality was high, particularly among the elderly and those with underlying conditions.

For the Party Elders, many of them in their seventies and eighties, it was no ordinary flu. It was a predator that stalked the Politburo’s smoky meeting rooms.

April 1983 – The First Blows

In the cavernous Great Hall of the People, the March meeting of the Standing Committee saw unusual coughing fits. Chen Yun, the cautious economic patriarch, took to speaking less and less during sessions, his voice raspy, his once-commanding presence diminished.

Li Xiannian, then the President of the PRC, missed a full week of meetings — officially due to “fatigue,” unofficially because he was bedridden with a high fever.

By May, reality could not be hidden. State media never said “pandemic,” but the coded phrase “seasonal epidemic wave” appeared in Renmin Ribao. Among the Eight Immortals, the health toll was severe:

- Li Xiannian – Never fully recovered; by summer, his voice was faint and he stopped attending public ceremonies.

- Song Renqiong – Hospitalized for three weeks; returned to work but visibly frailer.

- Wang Zhen – Defiant, but his immune system weakened; chronic complications lingered.

- Deng Yingchao – Caught the fever in June; though she survived, her doctors ordered a reduced schedule.

- Bo Yibo – Only mildly affected; joked that “Shanxi air kills all germs.”

- Peng Zhen – Escaped infection entirely, earning the half-joking nickname The Iron Phoenix.

- Chen Yun – Struck hard; survived, but the illness damaged his lungs. He reduced his workload drastically.

Two did not survive the year. In August, Li Xiannian succumbed to pneumonia following complications from the fever. In October, Song Renqiong passed away unexpectedly after a relapse.

Political Shockwaves – Late 1983

The loss of Li and Song in rapid succession tore gaping holes in the conservative bloc. The so-called Elders’ Council — an informal veto power over reform — was suddenly leaderless in some quarters. Deng Xiaoping, still spry at 79 and untouched by the fever thanks to a combination of elite healthcare and strict isolation, saw an opportunity.

“Without Li to hold the brakes,” Deng remarked privately to Hu Yaobang, “we can drive faster — as long as the road doesn’t break beneath us.”

Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang, both spared from serious illness, began pushing bolder reform proposals:

- Expanding Special Economic Zones beyond Guangdong and Fujian.

- Loosening controls over rural markets nationwide.

- Testing limited village-level elections for township chiefs.

1984 – The Pendulum Swings

Wang Zhen, though weakened, tried to rally conservatives, warning of “capitalist rot” and “spiritual pollution.” But without Li Xiannian’s prestige or Song Renqiong’s control over the Organization Department, his words carried less weight.

The decisive moment came in October 1984, when the 12th Central Committee’s Third Plenum convened.

- Deng Xiaoping and Hu Yaobang engineered a sweeping endorsement of economic liberalization, pushing forward urban enterprise reforms.

- Chen Yun, still an influential symbol, was too ill to mount a full opposition. His “birdcage” warnings were noted but largely ignored.

- Bo Yibo, opportunistic as ever, sided with Deng — sensing the winds had shifted.

The result: reforms leapt forward nearly five years ahead of schedule compared to our original timeline. Shenzhen exploded with investment; Shanghai began preliminary talks with foreign joint ventures much earlier than in reality.

1985 – The New Order

By early 1985, Beijing’s political chessboard had been re-set. The Elders’ Council no longer met with the same authority; the long table in their traditional conference room felt emptier. Of the old guard, only Wang Zhen, Bo Yibo, and a half-active Chen Yun still tried to assert weight.

For Deng, this thinning was a double-edged sword. He had lost comrades with whom he shared the marrow of the revolution — men he could argue with brutally and still drink tea with after — but he had also lost the only ones who could enforce the unspoken rules. The most important of these rules was never written down: the torch must pass to our bloodlines. Sons, nephews, and protégés of their own generation would inherit the Party’s real levers, no matter how the state modernized.

This was not just sentiment; it was self-interest intertwined with legacy. Several elders’ children already held lucrative posts in foreign trade companies and quasi-private “collectives,” moving goods through the new Special Economic Zones with margins that ordinary merchants could not touch. Students and small-town traders whispered the word 官倒 (insider profiteering) with contempt; the elders treated it as a regrettable but inevitable side effect of reform — as long as the right families profited.

The Conservative Young Guard

In this reconfigured landscape, one figure stood out among the younger conservatives: Li Peng. At 57, he was no revolutionary veteran — he was a “princeling” in the truest sense, the adopted son of Zhou Enlai’s old comrade Li Shuoxun, raised in part under Zhou’s protection after his father’s martyrdom. Trained as an engineer, Li was fluent in the language of planning and discipline, which made him an ideal custodian of the conservatives’ economic caution.

Li Peng’s rise in this alternate 1985 was slightly different from reality. With several elder conservatives gone or weakened by the 1983 plague, Li became their living bridge to the next generation. Chen Yun and Wang Zhen saw in him someone who could carry their “birdcage” economic philosophy forward without the rough edges of their own wartime rhetoric. His technocratic style, while stiff, reassured those in the ministries that feared Hu and Zhao’s experiments might unleash inflation, unemployment, or social instability.

Deng recognized Li’s utility — not as a future paramount leader (Hu still had that slot), but as a counterweight in the State Council to keep Zhao Ziyang from running the reformist engine too hot. In a meeting with Bo Yibo that winter, Deng remarked, “If Hu and Zhao are the sails, Li Peng will be the keel. Without the keel, we might flip.” It was both a compliment and a warning.

Hu’s Wave and the Elders’ Anchors

Hu Yaobang’s rise was undeniable. With Deng’s backing, he filled provincial posts with men like Li Ruihuan in Tianjin, Qiao Shi in the Organization Department, and Hu Qili in the Secretariat — a younger, better-educated cadre with cleaner reputations. Zhao Ziyang accelerated price reform proposals that in reality would have waited until 1987–88, buoyed by foreign interest in Shanghai’s tentative joint ventures.

The “retirement” of 1985, announced at the 12th Central Committee’s 5th Plenum, formalized the shift. Dozens of revolutionary veterans stepped down from Politburo or ministerial roles, moving to advisory committees. But everyone knew many still had phones that rang straight into Zhongnanhai. Wang Zhen’s son took a vice-ministerial post in the Ministry of Railways. Bo Yibo’s son, Bo Xilai, was promoted to a Party position in Dalian. Chen Yun’s protégés were quietly embedded in the State Planning Commission.

Li Peng’s appointment as a Vice Premier that autumn gave conservatives a seat in the economic cockpit. It also reassured the elders that their bloodline stake in the future was secure: Li might not be their son by birth, but he was their son in political inheritance.

Foreign correspondents in Hong Kong and Tokyo began to call this period the “Chinese Spring”, likening it to Gorbachev’s early glasnost. But inside the Party, it felt more like a thaw with patches of ice still floating. The conservatives’ institutional grip had weakened, but not their will to reassert control if “liberalization” overstepped. Younger hawks in the security services — protégés of Wang Zhen, protégés of Li Peng from his Ministry of Power days — were already cataloguing professors, editors, and students they deemed “suspect.”

The river was flowing faster, but the men on its banks were still measuring where to build the next dam.

Key Political Figures – Late 1985 (Alternate Timeline)

| Name | Age (1985) | Faction | Position | Health (Post-1983) | Personal Tie to Deng | Notes & Background |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deng Xiaoping | 81 | Reform-leaning pragmatist | Chairman of CMC; Paramount Leader | Healthy | N/A (central figure) | Architect of Reform & Opening; balances reformists & conservatives; protects elders’ generational interests. |

| Hu Yaobang | 70 | Reformist | General Secretary of CCP | Healthy | Deng’s chosen political heir for political reform | Advocates political openness; promotes younger, cleaner provincial leaders. |

| Zhao Ziyang | 66 | Reformist | Premier of the State Council | Healthy | Deng’s chosen economic reform executor | Pushes market reforms; careful not to alienate Deng’s conservative allies. |

| Li Peng | 57 | Younger conservative | Vice Premier of the State Council | Healthy | Political “godson” to elder conservatives; Zhou Enlai’s protégé | Technocrat; carries Chen Yun’s cautious economic philosophy; bridge to next-gen conservative bloc. |

| Wang Zhen | 75 | Hardline conservative | Vice President of PRC | Survived plague; stamina reduced | Fellow Long March veteran; shared wartime bond | Fierce opponent of liberalization; promotes his son’s career in infrastructure ministries. |

| Bo Yibo | 77 | Opportunist (leaning reform) | Vice Premier (Economic Affairs) | Healthy | Longtime political ally | Pragmatic; family involved in early hybrid-economy enterprises (官倒 rumors). |

| Chen Yun | 80 | Conservative economic planner | PSC Member (retired from formal gov. role) | Chronic lung damage from plague | Deng’s equal in revolutionary prestige | “Birdcage” economic theorist; places protégés in State Planning Commission. |

| Peng Zhen | 83 | Centrist institutionalist | NPC Chairman | Healthy | Deng’s comrade from early Party years | Legalist mediator; helps shape controlled political reforms. |

| Deng Yingchao | 81 | Reform-leaning elder | NPC Vice Chairwoman | Recovered from 1983 fever | Widow of Zhou Enlai; moral influence | Cultural and women’s rights advocate; supports Hu’s openness agenda. |

| Yang Shangkun | 78 | Military-leaning centrist | Exec. Vice Chair of CMC | Healthy | Military ally; trusted with PLA control | Ensures PLA loyalty; balances between Hu/Zhao and conservative generals. |

| Li Ruihuan | 51 | Reformist rising star | Party Secretary of Tianjin | Healthy | Promoted by Hu | Skilled urban manager; popular among workers for pragmatic problem-solving. |

| Qiao Shi | 61 | Reformist pragmatist | Head of Central Organization Department | Healthy | Supported by Deng for organizational skill | Trusted to manage cadre appointments after Song Renqiong’s death. |

Leave a comment