1993 – The honeymoon ends

The first elections and the cracks beneath

Township elections in Guangdong and Sichuan went ahead in spring 1993. On paper, they were modest: candidates vetted for basic loyalty to the PRC constitution, but allowed to campaign openly and debate local budgets.

Results:

- In richer coastal towns, turnout exceeded 80%, and candidates often won on promises of road-building, school expansions, or tax relief for small businesses.

- In poorer inland areas, turnout was lower, and clan networks dominated. In one Sichuan township, the winning candidate was a respected funeral goods merchant — because he promised to waive coffin fees for the poor.

Beijing congratulated itself, but the Research Office quietly noted “risk of localism” and “persistence of feudal influence.”

The ghosts of the Cultural Revolution

The 1993 National People’s Congress faced a symbolic but explosive question: what to do with the last imprisoned leaders of the Cultural Revolution, including Jiang Qing and Wang Hongwen.

- Hardliners wanted them to remain in custody for life: “To release them is to invite ghosts back into the house.”

- Reformers, Hu included, argued for closure: “Justice delayed for decades is not justice — it is vengeance.”

The compromise: commutations to house arrest, under strict silence orders. Jiang Qing was moved to a guarded villa outside Beijing; Wang Hongwen returned to Shanghai under constant surveillance. To Maoist loyalists in the countryside, even this was “humiliation of the Chairman’s wife.” To students and liberals, it was a half-measure.

Economic fault lines emerge

Hu and Zhao had always agreed on political opening. But 1993’s budget meetings revealed the economic split.

- Hu Yaobang: favored gradual restructuring, keeping large state-owned enterprises (SOEs) afloat to avoid mass layoffs and urban unrest. He argued that “political openness will fail if the people starve.”

- Zhao Ziyang: believed China must privatize aggressively to avoid falling into the inefficiency trap that had doomed Eastern Europe’s gradualists. He warned, “The longer we keep dying factories alive, the heavier the debt on the living.”

The issue wasn’t abstract — over 80 million Chinese still worked in SOEs, many in heavy industry towns where the factory was the economy.

1994 – Reform meets resistance

The layoffs begin (and the protests too)

In January 1994, Zhao pushed through a pilot privatization program in Liaoning, selling or leasing 50 mid-sized SOEs to private investors. Within months, layoffs hit 40,000 workers.

- In Shenyang, laid-off workers marched with banners: We built the Republic — now the Republic abandons us!

- In smaller cities, jobless men gathered at tea stalls, swapping rumors of “foreign capitalists” buying factories for scrap.

Hu publicly called for “a pause” in further privatizations. Zhao countered in People’s Daily: “Pausing now means condemning China to a half-reform, half-stagnation death.”

Mao’s shadow reappears

With the economic unease came a resurgence of Maoist nostalgia. In some rural areas, portraits of Mao replaced the national emblem in township offices. A new underground journal, Red Dawn, openly criticized “bourgeois reformers” and praised the Cultural Revolution’s “purity.”

Hu saw this as a cultural problem: “We did not explain reform to the people.” Zhao saw it as political sabotage: “You can’t reason with a cult.”

International worries

Foreign investors, buoyed by the political stability after 1989, began to worry about the reform split. Hong Kong tycoons, in particular, pressed Beijing to “choose a path” before 1997’s handover.

1995 – The first real national test

The general election framework

By late 1994, the plan was set:

- National People’s Congress elections in mid-1995, with 40% of seats open to genuinely competitive races (local nominees vetted only for constitutional loyalty).

- Party would remain dominant in military and foreign affairs, but legislative control could influence budgets, oversight, and anti-corruption laws.

It was historic — and dangerous.

Campaign season: two visions of reform

Though not running against each other directly, Hu and Zhao became the symbolic leaders of two currents:

- Hu’s camp (“稳进” – Steady Advance): Keep SOEs in key sectors, invest heavily in rural education and healthcare, expand political rights slowly but broadly.

- Zhao’s camp (“速改” – Swift Reform): Accelerate privatization, attract foreign investment, and shift welfare to a targeted safety net rather than universal guarantees.

In campaign speeches across the provinces, the division sharpened. In Tianjin, Zhao warned:

“If we cling to every brick of the old factory, we will sink with it.”

In Xi’an, Hu replied:

“A bridge must carry all who cross — not just the fastest runners.”

The country divides

The split wasn’t just elite:

- Coastal cities (Shenzhen, Shanghai, Guangzhou) leaned toward Zhao’s vision, seeing privatization as the path to wealth.

- Inland provinces and industrial rust belts rallied to Hu, fearing the social collapse they saw in post-Soviet Eastern Europe.

- Rural voters were mixed, often swayed by clan networks or promises of local infrastructure over ideology.

Maoist groups, though small, campaigned noisily for “neither Hu nor Zhao” — calling for a return to “pure socialism.”

The election results (late 1995)

When the ballots were counted:

- Hu’s steady-advance candidates dominated in the interior and the northeast.

- Zhao’s swift-reform slate swept the southern coast and major trade hubs.

- Maoist independents won a handful of symbolic seats, mostly in poor inland districts.

The NPC was almost evenly split between the two reformist blocs — neither with a commanding majority. It was the most divided legislature in PRC history.

Beijing after the vote

The shared leadership of Hu and Zhao survived — barely. Both knew that if they split completely, they risked opening the door to a conservative revival, even with the elders’ bloc much diminished.

Yet 1995 ended with an uneasy truth: China had begun its peaceful evolution, but its two architects were no longer rowing in sync. And in a country still poor, still scarred by its past, still learning what a vote meant, the danger was no longer just whether democracy could work — but whether reform itself could survive its own contradictions.

1996 – The quiet breaking point

Economic split becomes political

By early 1996, the nearly 50–50 NPC from the 1995 election had become a logjam.

- Hu’s “Steady Advance” bloc was pushing for new subsidies to keep thousands of struggling inland SOEs open, fearing mass layoffs would spark unrest in already restive cities like Harbin and Lanzhou.

- Zhao’s “Swift Reform” bloc wanted a timetable for privatizing 80% of SOEs within five years, channeling funds into high-tech zones, ports, and special economic corridors.

Months of negotiation produced nothing but frustration. Each side accused the other — politely, in public; sharply, in private — of risking China’s future.

The autumn conversation

In October 1996, Hu invited Zhao to his study in Zhongnanhai. The tea was old pu-erh, their usual choice. They sat for a long time without touching the cups.

- Hu: “Old Zhao, we’ve been rowing in the same boat since the early 80s. But now, you row south and I row north.”

- Zhao: “The river’s too wide to row together. And neither of us can turn the other’s boat.”

- Hu: “Then maybe we sail separately… and see which boat the people choose.”

- Zhao: “If we do this, it’s the end of the Party as we knew it.”

- Hu: “Maybe that’s the point. We can’t hold the river with a rope forever.”

December 1996 – The shared statement

On December 28, 1996, Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang held a joint press conference in the Great Hall of the People. Their statement — historic in modern Chinese history — began:

“The People’s Republic was founded in unity, but unity without choice is stagnation. We believe that the strength of our nation now lies in giving its citizens the power to choose their leaders and their policies.”

They announced the formal end of the CCP’s monopoly on political power, effective immediately, and the formation of two new parties:

- The Democratic Reform Party (Hu) — gradual economic change, strong social safety nets, emphasis on rural development and national unity.

- The Liberal Progress Party (Zhao) — rapid market reform, deeper integration with the global economy, targeted welfare, and regional autonomy in economic matters.

The NPC passed the transition law within a week — many members had already aligned with one or the other bloc, so the vote was more about formalizing reality than creating it.

1997 – The Year an Era Came to a Close

The last year of Deng

Deng Xiaoping, now 92, was bedridden in his family compound. Reports from his aides said he watched the December announcement on television in silence. He told his daughter later:

“I didn’t think I’d live to see the Party end. But I see the men who ended it, and I know they are still my comrades.”

In February, Deng summoned both Hu and Zhao for what everyone understood would be their final meeting.

- Deng: “You’ve divided the Party, but you haven’t divided China. That is your greatest achievement.”

- Hu: “We built this on your restraint in ’89. Without that, there would be no choice to make now.”

- Zhao: “History will remember you, Lao Deng — for what you did, and for what you didn’t do.”

They sat together for a photograph — three old men, tired but smiling. It would be published the day after Deng’s death.

February 19, 1997 – Deng’s passing

When Deng died, the state declared a week of mourning. His funeral at the Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery was attended by both Hu and Zhao, standing side by side for the last time before the cameras. Crowds along Chang’an Avenue waved both party flags — red for Hu’s DRP, blue for Zhao’s LPP — a sight unthinkable a decade earlier.

The eulogies were simple:

- Hu: “He taught us that China’s strength is its people, not its slogans.”

- Zhao: “He left us not orders, but choices. That is his legacy.”

July 1, 1997 – Hong Kong’s return

The ceremony in the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre was unlike any other in PRC history: two prime ministers, one from each major party, both standing under the same flag.

Hu and Zhao attended together as “Elders of the Republic.” The British Governor, Chris Patten, shook both their hands.

Hu whispered to Zhao during the anthem:

“This is the last time we’ll stand like this.”

Zhao smiled faintly:

“Then let’s make it count.”

When the flag was raised, they saluted — not as CCP leaders, but as the two men who had, through survival, compromise, and respect, taken China from one-party rule into its uncertain, difficult, but bloodless experiment in choice.

It was their final shared public moment. From then on, history would judge them separately — but always as part of the same story.

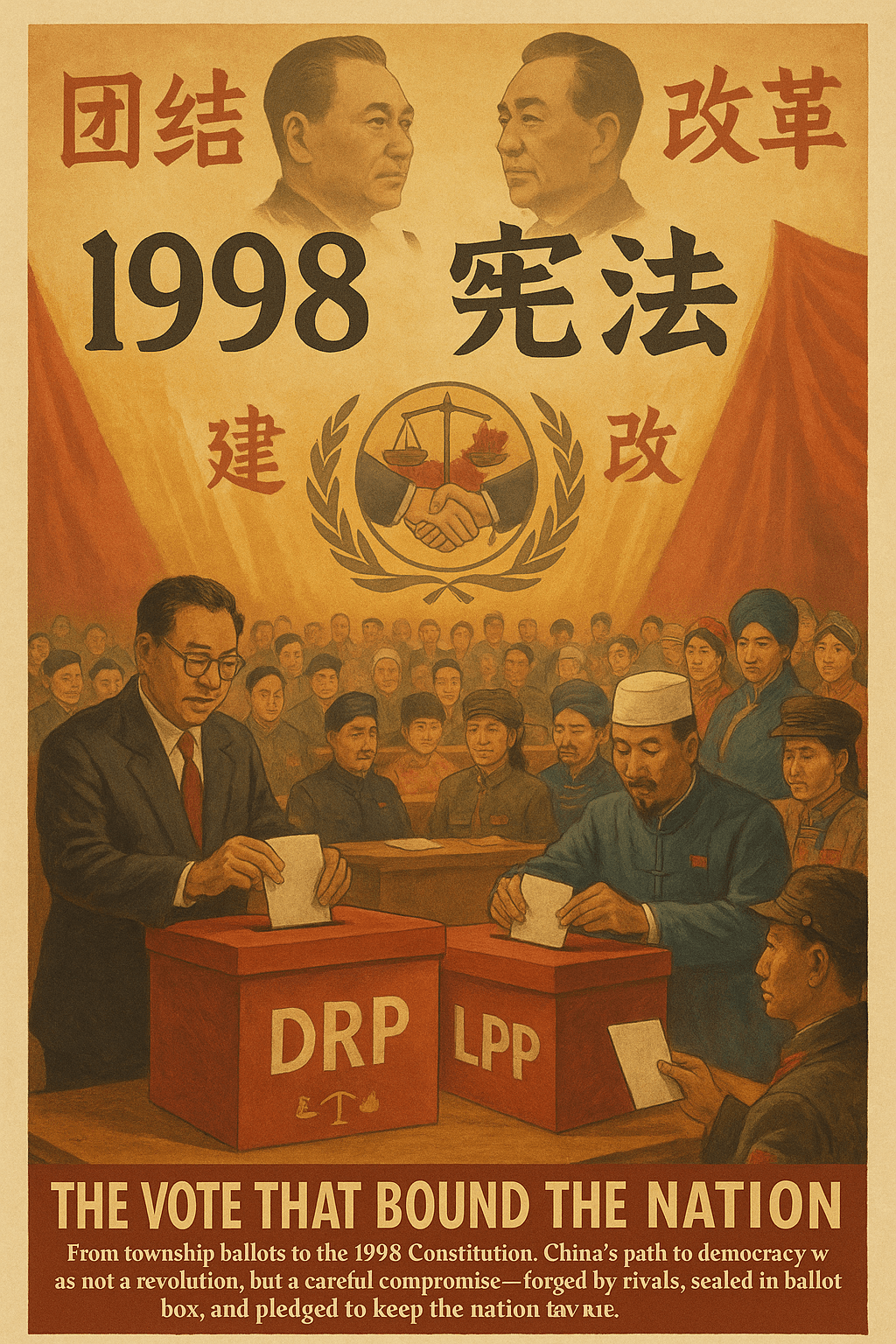

The 1998 Constitution and the First Presidential Election

From Transition to Codification

In the wake of Deng’s passing and Hong Kong’s return, the two new major parties — Democratic Reform Party (DRP) led by Hu Yaobang and Liberal Progress Party (LPP) led by Zhao Ziyang — faced their next challenge: to formalize China’s new system in law.

The 1998 Constitution, passed by the newly reconfigured National People’s Congress, was the product of months of cross-party negotiation.

Key Features of the 1998 Constitution

- Semi-Presidential System

- Direct popular election of the President every 5 years.

- President shares executive power with the Premier (appointed by the President but confirmed by the legislature).

- President = Head of State, foreign policy lead, commander-in-chief.

- Premier = Head of Government, domestic policy and economic management.

- Bicameral Legislature

- National Assembly (lower house) — elected via proportional representation; main lawmaking body.

- Council of Provinces (upper house) — provincial delegates; checks over central laws that affect local autonomy.

- Party System Rules

- Parties must affirm the Constitution, sovereignty of PRC, and peaceful political competition.

- Military remains nonpartisan under constitutional oversight.

- Judicial Independence

- Constitutional Court to arbitrate disputes between parties and levels of government.

- Unity Clause

- No region may secede; disputes must be resolved through the Council of Provinces.

The First Presidential Election – 1998

With Hu and Zhao both retiring from executive politics (remaining “Elders of the Republic”), their parties put forward new standard-bearers.

- Democratic Reform Party (DRP) — Nominated Bo Xilai, the charismatic Mayor of Dalian, known for his flair in public speaking, populist style, and promises to balance rural welfare with urban development.

- Liberal Progress Party (LPP) — Nominated Jiang Zemin, the sitting Vice President, respected for his technocratic skills and deft handling of foreign relations during the Hong Kong handover.

Campaign Themes:

- Bo (DRP): “A bridge for all” — pledged gradual economic reform, stronger rural investment, nationwide infrastructure renewal, and protections for state-sector workers.

- Jiang (LPP): “Leap forward without fear” — promised faster privatization, deeper global integration, and coastal-led growth to pull the interior along.

Result:

Jiang Zemin (LPP) won with 54% of the vote to Bo Xilai’s (DRP) 45% (1% scattered among minor candidates).

The LPP secured a slight majority in the National Assembly, while the DRP held stronger influence in inland provinces and in the Council of Provinces.

The Unity Promise

After the results, Jiang and Bo appeared together on national television, signing the Unity Accord:

“Though we compete for leadership, we are united in the sovereignty, stability, and progress of the People’s Republic of China. No election shall divide the nation we both serve.”

It was a deliberate message to both domestic and foreign audiences — that China’s multi-party democracy would not dissolve into fragmentation.

Leave a comment