July–September 1989 – The summer fade

By July, the constant rallies had dwindled to occasional vigils. The hunger strike had ended weeks earlier, and university administrators began coaxing students back to classes with promises of leniency on missed exams.

The Harbin leak and Nanjing land scandal that had fueled the protests didn’t disappear — in fact, they were used as training case studies for new anti-corruption “inspection teams” that Hu Yaobang insisted be formed in every province.

These teams looked busy, but in reality had mixed success: some genuinely rooted out graft; others were just new fiefdoms for local officials.

The conservatives, still bitter over the June non-crackdown, retreated into a kind of tactical sulking. Wang Zhen, his health declining, stopped attending every meeting, but still kept a sharp tongue in private:

“We didn’t lose the Square. We just gave it a stool and tea and asked it to sit down.”

Autumn 1989 – The Berlin Wall shakes

In September, foreign news began trickling in through Hong Kong and foreign embassies:

- In Poland, the Communist Party had ceded power to Solidarity.

- In Hungary, the border to Austria had opened.

- East Germans were leaving through Prague and Budapest.

The elders reacted with a mix of disbelief and dread. Chen Yun, now too frail to leave his home, sent a letter to Deng warning: “Socialism without discipline becomes driftwood.”

Deng read it aloud to the Standing Committee, not to endorse it, but to remind them that the Party’s survival was not guaranteed by mere history.

Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang saw the Eastern Bloc’s loosening as a caution and an opportunity — proof that political systems could adapt without collapse if handled carefully. Wang Zhen saw only collapse.

November 1989 – The Wall falls

When the Berlin Wall actually came down on November 9, the Zhongnanhai mood turned to steel-gray.

For the younger cadres, it was a marvel; for the elders, a warning siren. The images of Germans dancing on the wall, breaking off chunks for souvenirs, reminded them uncomfortably of the Goddess of Democracy in Tiananmen.

Deng convened a closed elders’ session in mid-November. The consensus: China’s reforms would continue economically, but political opening must be kept on a short leash. Hu, still technically General Secretary, was allowed to speak — he argued for more public engagement to “keep the rope from snapping.”

Wang Zhen shot back: “If you give them the rope, they’ll use it to hang you.”

Winter 1989 – Losses among the Eight Immortals

The strain of the year and advancing age took its toll.

- Chen Yun died quietly in December 1989 at the age of 84. Deng personally attended the funeral, speaking of him as “a man whose caution kept our foundation strong.”

- Wang Zhen, already weakened, suffered a serious stroke just before the Lunar New Year 1990. He would never fully return to political life.

These deaths — and near-deaths — exhausted the elders’ council even further. Deng’s emotional ties to them were deep; he had fought alongside these men for half a century. Now, fewer and fewer shared that battlefield memory.

Early 1990 – A quieter, brittle China

By spring 1990, the universities were quiet again, but the memory of 1989 lingered like the smell of smoke after a fire. Students who had marched were graduating into an economy that was growing in the south but stagnant in the north, with prices still unstable.

Hu Yaobang continued his “long-term studies” role, making provincial inspection tours that drew warm crowds but little concrete policy change. Zhao Ziyang was the day-to-day manager of reform, careful not to provoke either side.

Deng, now 86, spoke less in meetings but still set the tone:

“We’ve seen what happens to those who forget stability. Let’s not join the list.”

Mid–Late 1990 – Watching the Bloc dissolve

Through summer and autumn, the news from Europe was relentless: the Soviet republics demanding independence, Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution, Romania’s violent overthrow. Each event was studied in detail by the Central Committee’s Research Office — not for admiration, but for lessons in what to avoid.

In October 1990, Wang Zhen passed away at age 89. His funeral was smaller than Chen Yun’s but carried heavy symbolic weight: with his death, the conservatives lost their most vocal hardliner, and the balance in the Standing Committee tipped slightly toward Zhao and Hu’s cautious reformism.

Deng delivered the eulogy:

“Comrade Wang was a man who feared no enemy and spoke no soft words. We will remember his courage, and we will carry forward his spirit in our own way.”

January–March 1991 – The Soviet tremor

The Gulf War dominated the world’s TV screens in January, but inside Zhongnanhai the focus was elsewhere: Moscow.

The Soviet economy was in free fall; republic after republic was pushing for sovereignty. In the Party’s Research Office, a series of “Red Alerts” crossed Deng’s desk: If the USSR collapses, the ideological foundation of global socialism will be gone.

Hu Yaobang saw an opening:

“If socialism in Europe collapses in chaos, we can show that reform here means stability. That will be our example to the world.”

Conservatives like Bo Yibo, though weakened by age, still warned: “Peaceful evolution is just surrender in slow motion.”

But without Wang Zhen, there was no one to pound the table and demand force.

Mid-1991 – The August Coup

When the Soviet hardliners attempted their coup in August, the CCP elders watched in silence as tanks rolled through Moscow — then rolled back.

Deng’s comment was terse:

“Force without legitimacy is a gun without bullets.”

Hu and Zhao took note. They began drafting a gradual plan for political reform, starting at the township level and moving upward — a controlled release of political steam.

December 1991 – The hammer falls

The Soviet Union dissolved on December 26. In Beijing, there was no panic, just a heavy, still air.

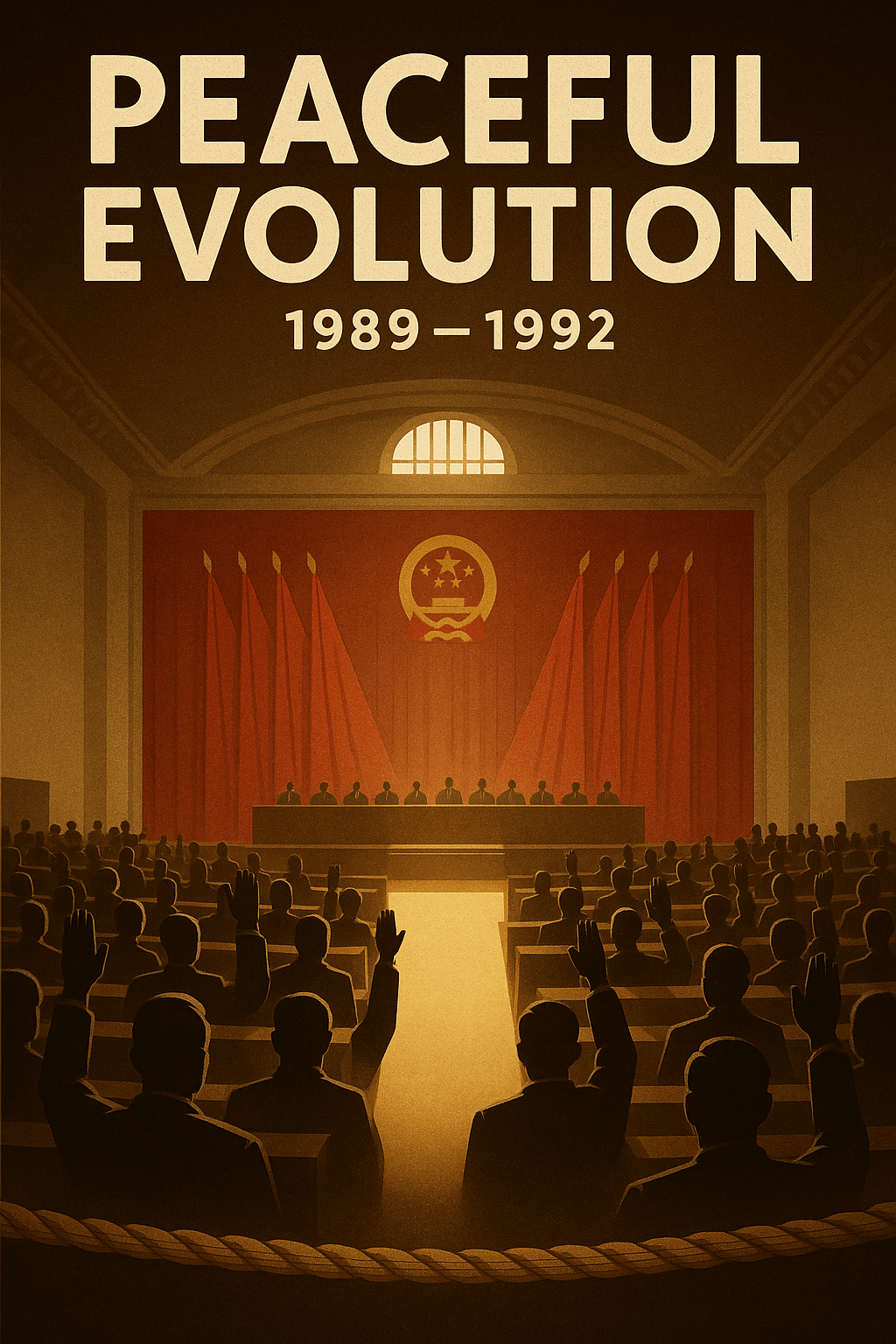

The elders gathered in the Great Hall, some too frail to walk without aides. Deng looked around the table and realized: nearly all the faces he’d once fought alongside were gone. Chen Yun, Wang Zhen, Li Xiannian, Song Renqiong — all buried. Only Bo remained from the old guard, and even he looked tired.

Early 1992 – Deng’s last gamble

In our reality, Deng launched his “Southern Tour” to reassert economic reform after the post-Tiananmen freeze. In this world, he did something bigger — and riskier.

In February 1992, Deng boarded the train south with both Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang. At each stop — Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai — he delivered a new line in his speeches:

“Stability comes from trust. Trust comes from openness. Without the people’s voice, there is no long-term prosperity.”

The crowds were enormous. Hong Kong media splashed the images across the border.

April–August 1992 – The evolution begins

Following Deng’s return to Beijing, the National People’s Congress passed a package of reforms:

- Township elections across the country by 1995.

- Expanded press rights for China Youth Daily and other state outlets to investigate corruption without prior Party clearance.

- A formal commitment to publish draft laws for public comment before passage.

It wasn’t Western democracy — but it was the first real institutional step toward what foreign analysts called “a hybrid system.”

Conservatives grumbled, but Deng’s prestige, and the economic boom in the south, gave reformers the upper hand.

November 1992 – Deng’s farewell

On November 8, at the opening of the 14th Party Congress, Deng took the rostrum for what everyone knew would be his last major address. His voice was thin but steady:

“I have seen war and famine, chaos and unity. I have seen comrades die in battle and in peace.

What I have learned is this: a nation cannot be preserved by fear alone.

We must have courage not only to fight, but to listen.

I am leaving the work to younger hands, who will make mistakes, and learn from them, and be better for it.

This is my last gift to the Party and to China — not an order, but a chance.”

He stepped down to sustained applause, some of it damp-eyed. In that moment, even Bo Yibo stood and clapped.

End of 1992 – The first signs of change

By year’s end:

- The first competitive township elections were scheduled in Guangdong and Sichuan.

- Investigative reports into provincial corruption ran in major newspapers without prior censorship, shocking older cadres but thrilling younger ones.

- Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang shared leadership in a reformist partnership that balanced political opening with rapid economic growth.

Deng retired fully to his family compound, spending his mornings in the garden. He received visitors rarely, and when he did, he would smile and say:

“The rope is in their hands now. Let’s see if they can keep it from breaking.”

Key Exiting Figures (1989–1992)

| Name | Exit Year | How They Exited | What It Meant Politically |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chen Yun | Dec 1989 | Died after prolonged illness | Removed the core economic conservative. After his death, the “birdcage” veto faded; reformers faced less elder pushback. |

| Wang Zhen | Late 1990 | Died of illness | The loudest hardliner disappeared; conservative morale dipped and their leverage over security organs weakened. |

| Bo Yibo | 1991 | Withdrew from front-line politics; formal retirement to “advisory” | Ended the elder-broker era. His exit removed the key opportunist dealmaker linking old-guard interests to new hybrid-economy networks. |

| Deng Yingchao | 1992 | Passed away | Loss of cross-faction moral authority; one less “bridge” voice capable of cooling tempers in crisis. |

| Peng Zhen | 1992 | Retired due to age | Legalist stewardship of reform moved to younger hands (set up Qiao Shi/NPC ascendance). |

| Li Peng | 1990 (political exit) | Sidelined from succession; kept to non-core portfolios | Conservative “younger guard” lost their standard-bearer at the center; ended his premiership path in this timeline. |

| Deng Xiaoping | Nov 1992 | Voluntary retirement with farewell address | Passed the torch to institutional leadership; removed the last personal arbiter, forcing factions to bargain inside rules. |

New Leadership Group (circa 1992)

| Name | Age (1992) | Position (1992) | Faction | Political Reform Stance | Economic Model Preference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hu Yaobang | 77 | President of the PRC (symbolic head; co-architect of transition) | Reformist | Gradual democratization from local upward; protect civil space | Market opening + social safety net; anti-corruption priority |

| Zhao Ziyang | 73 | Premier; CCP Chair in transition framework | Reformist | Faster political opening; competitive elections inside constitutional guardrails | Market-led reform, FDI, SOE hard restructuring |

| Jiang Zemin | 66 | Vice President; PSC | Reform-leaning centrist | Limited political liberalization under firm center | Export-led growth; cautious privatization; tech & coastal focus |

| Zhu Rongji | 64 | Vice Premier (Economy/Finance) | Technocratic reformist | Governance first; clean state, credible rules | Tight macro control; bank/SOE reform; anti-inflation shock therapy if needed |

| Li Ruihuan | 58 | PSC; NPC Standing Committee Vice Chair | Moderate reformist | Expand worker voice; widen local elections gradually | Gradual privatization + urban welfare guarantees |

| Qiao Shi | 68 | PSC; Political–Legal Affairs (moving to NPC leadership track) | Legalist reformer | Rule-of-law first; codify rights before broad contests | Market economy bounded by independent oversight |

| Hu Qili | 63 | Executive Secretary of Secretariat; Propaganda/Ideology | Liberal reformist | Open media space; institutionalize press protections | Pro-market with transparency to check capture |

| Hu Jintao | 50 | Politburo; moving from Tibet to Secretariat | Cautious reformist (Tuanpai) | Orderly political opening; social stability & poverty relief | Balanced growth; inland investment; risk-averse on shocks |

| Tian Jiyun | 63 | State Council Sec-Gen | Reformist | Slim bureaucracy; procedural governance | Marketization in agri/industry; admin streamlining |

| Wen Jiabao | 50 | Deputy Director, Central Office (entering State Council core) | Technocratic reformist | Consensus-building; policy transparency | Rural health/education + infrastructure-led domestic demand |

Leave a comment